S

otheby's proudly presents Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Works of Art, a live auction taking place in New York on 20 September at 11:00 AM EDT. The small but jewel-like collection of works features magnificent examples of Himalayan sculpture led by an important central Tibetan figure of Manjushri dating to the 12th/13th Century from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Collection, along with a superb Gandharan Bodhisattva together with fine examples of Southeast Asian sculpture from the MacLean Collection. Other highlights of the sale include a rare 14th Century triad of Vishnu with Sridevi and Bhudevi from South India, a 15th Century Tibetan Mahakala thangka on blue silk, a 13th/14th Century Nepalese gilt-copper sculpture of Mahalakshmi, and a set of eighty-eight Jain manuscript pages. These masterpieces will join other treasures of sculpture and painting from the Himalayas, South and Southeast Asia.

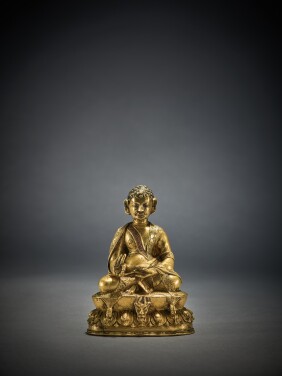

In the 12th/13th Century, far above the clouds in high-mountain Asia, this copper alloy figure of bodhisattva Manjushri broke from its mold for the first and only time. Created using the lost wax technique in central Tibet, the mould was destroyed in the process of its creation, making it impossible to duplicate. Modeled after the classic Nepalese standing bodhisattvas of the Transitional Period, Manjushri is identified as the deity of transcendent wisdom and was meant to serve as a personal guide along the path to enlightenment. On behalf of the world-renowned Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, Sotheby's is pleased to offer this rare standing sculpture of Manjushri this September.

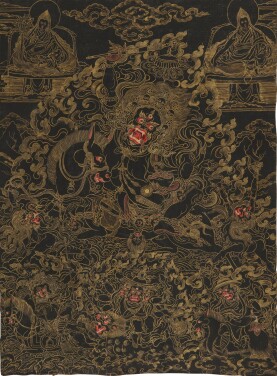

The imagery of wrathful protector deities in the Tantric or Vajrayana Buddhist pantheon can be mystifying to the untutored eye. Bulging eyes, flaming hair, bared fangs, impaled flesh, trampled humans, flayed animal skins, garlands of severed heads, skeletons and menacing weaponry all contained in a single image can seem eccentric. In appearance, these demonic figures look murderous and prideful, and in fact they are, as they wear their spoils from subjugated beings as ornaments. The Vajrayana tradition, or tantric Buddhist path in Tibet, is often described as treacherous and unforgiving, and wrathful imagery is meant to serve as a guide for the practitioner to work with arising obstacles, often which are associated with the fixation on one’s own ego. While the origins of these images come from India from the model of rakshasa (male) or rakshasi (female) demon as described in Indian literature, their representations took on particular roles including protection, wisdom, power, wealth and purification within the various lineages of tantric Buddhism throughout Tibet. They serve as a counter-balance to the more benevolent classes of deities, though both, albeit through different methods, are meant to guide the practitioner through the adversities on the path to ultimate Enlightenment.

The figure of the bodhisattva occupies a prime place in Mahayana Buddhist theology. The bodhisattva is believed to be a sentient being who remains on this earth and postpones his own nirvana (release from the cycles of birth and death) to help others achieve salvation. Images of this youthful, altruistic deity – always depicted as a royal personage – were created in large numbers to populate the many Buddhist shrines and altars that were constructed in ancient Gandhara. These regal sculptures display a variety of artistic motifs drawn from the cultures of the cosmopolitan populace that inhabited the region.

The bodhisattva’s jeweled turban terminates in fluttering ends carved in relief on the halo framing his head. This ‘flying scarf’ motif is drawn directly from Sassanian royal imagery and is instantly recognizable in art from the region such as this silver plate from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum featuring a king on a hunt.

The bodhisattva’s necklaces display a combination of Indic and Hellenistic styles. The collar ornament or kanthi is of a type depicted widely in Indian sculpture whilst the pendent necklace displays the ubiquitous Hellenic ‘loop in loop’ chain with griffin terminals centering a gem.

The figure’s regal posture – one hand resting on his hip, the other now lost likely displaying abhayamudra or the gesture of protection – underscores both his Royal stature and benevolent nature.

The string of sacred amulets or kavacha worn prominently across the bodhisattva’s body highlight the protective and apotropaic qualities of the deity.

The well-modeled physique and deeply cut drapery are derived directly from the Greco-Roman tradition and are hallmarks of the art of Gandhara.

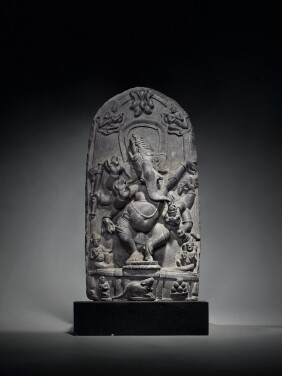

With its vast pantheon of Gods, Goddesses, celestial beings, attendant figures, mythical beasts and ornament, ancient sculpture from South and Southeast Asia abounds with a richness of diversity in form and mode that is unmatched. From the serene schist likeness of the Buddha created in the ancient region of Gandhara in the 2nd Century, or the lively 11th Century sandstone fragment of celestials being worshipped, and the 12th Century black stone stele of the cherished elephant-headed deity Ganesha in joyous dance, both from India, to the regal, statuesque portrait in sandstone of Vishnu as God King or devaraja from Southeast Asia, each image bears unique characteristics. The common thread that unifies them all is the life-force or prana that rests in each image, which conveys a distinctive impression to the viewer and brings the subject ‘alive.’ Despite the passage of centuries, these timeless works of art retain their mystique and allure.

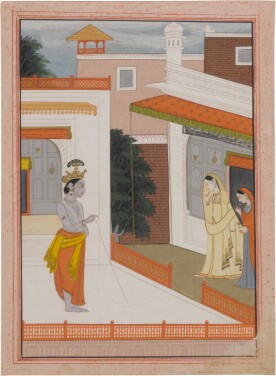

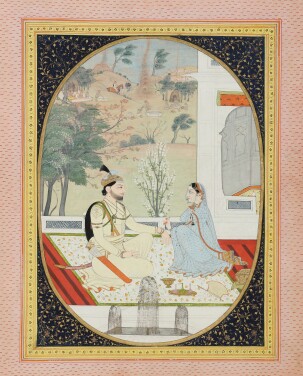

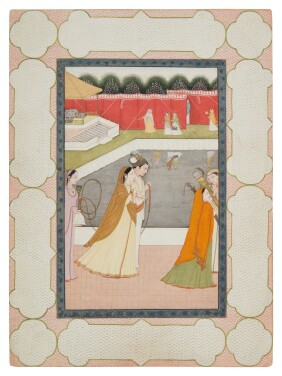

Rasa (lit. flavor) is the underlying esthetic principal in South Asian literature, music and art. From the very ancient period, poetry and prose composed in Sanskrit, and later in regional languages, was rich in allegory. With the establishment of important painting ateliers post the fifteenth century, artists transposed the sentiments and emotions effected in words in great literary works, into pictures. The various moods and dispositions of loving couples in particular was a very popular convention in Indian court painting. Ragamala illustrations attempted to convey the mood of the subject musical mode or raga by drawing attention to the background, time of day, and nature of engagement between in the couple – romantic, blissful, forlorn, in the image. Illustrations of heroes and heroines (nayaka-nayika) faithfully translated the emotions or bhava encoded in romantic literature – jealousy, anger, love play, into the paintings. This visual vocabulary was even deployed to depict the annual cycle of seasons or Baramasa with subtle details in the landscape, the couple’s attire and their activities – the lord enjoying cool breeze beneath a shade while the lady fans him, conveying the atmosphere of the month. Over time, representations of noble couples engaged in courtly activities – taking a stroll, playing chaupar, also gained currency. Picturized with lavish and loving detail, each situation captures perfectly the underlying emotion in the scene.