Bob Dylan | "All Along the Watchtower" in Dylan's own hand

Lot Closed

April 18, 02:35 PM GMT

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Bob Dylan

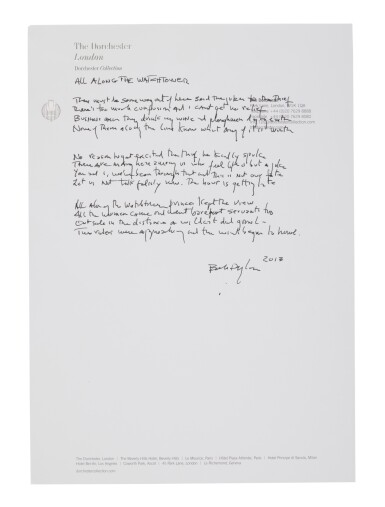

Autograph manuscript signed, being a fair copy of the lyrics to “All Along the Watchtower”

Autograph manuscript on one leaf (296 x 209 mm), titled “All Along the Watchtower” above 12 lines in three quatrains, signed (“Bob Dylan”) and dated 2013 below the lyrics, accomplished in black ink on The Dorchester London hotel stationary; very minor creasing. [With]: A letter of authenticity signed by Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen.

“There must be some way out of here,” said the joker to the thief

The lyrics to one of Dylan’s greatest achievements. The present fair copy abandons most of the punctuation and features several small changes to the definitive version as recorded. In the second line, Dylan inserts “and” between “confusion” and “I can’t get no relief”; in the third line, he inserts “and” between “my wine” and “ploughmen”; “but” is absent from the beginning of the seventh line; in the final line, he inserts “and” between “approaching” and “the wind.”

“All Along the Watchtower” appeared on the 1967 John Wesley Harding, his first album following his 1966 motorcycle accident and subsequent seclusion in Woodstock. The album marked a dramatic departure from his previous work; while the songs were notably pared down—in both composition and delivery—they were hardly a return to his folk roots. The album is steeped in biblical imagery, with the themes reaching their apotheosis in these lyrics:

‘All Along the Watchtower’ features perhaps the most overt biblical allusions, drawing its setting from the section of Isaiah that deals with the fall of Babylon. Yet the thief that cries ‘the hour is getting late’ is surely the thief in the night foretold in Revelation, Jesus Christ come again. It is He who says, in St. John the Divine’s tract: ‘I will come on thee as a thief, and Thou shalt not know what hour I will come upon thee.’ Dylan remained unsure of the hour at which he might come, later saying of John Wesley Harding that he had been ‘dealing with the devil in a fearful way.’ (Heylin 286)

In an interview with Happy Traum and John Cohen for the October/November 1968 issue of Sing Out!—his first since his disappearance from the public eye—Dylan addressed the formal nature of the lyrics frankly, if obliquely:

[John Cohen]: Then most of the songs on ‘John Wesley Harding,’ you don’t consider to be ballads.

[Dylan]: Well I do, but not in the traditional sense. I haven’t fulfilled the balladeer’s job. A balladeer can sit down and sing three ballads for an hour and a half. See, on the album, you have to think about it after you hear it, that’s what takes up the time, but with a ballad, you don’t necessarily have to think about it after you hear it, it can all unfold to you. These melodies on the John Wesley Harding album lack this traditional sense of time. As with the third verse of ‘The Wicked Messenger,’ which opens it up, and then the time schedule takes a jump and soon the song becomes wider. One realizes that when one hears it, but one might have to adapt to it. But we are not hearing anything that isn’t there; anything we can imagine is really there. The same thing is true of the song ‘All Along the Watchtower,’ which opens up in a slightly different way, in a stranger way, for we have the cycle of events working in a rather reverse order. (Cott 122)

While it is one of the most beloved tracks of Dylan’s career, it was The Jimi Hendrix Experience who immortalized the song in the rock canon. After Hendrix released his cover as a single ahead his third album, Electric Ladyland, “All Along the Watchtower” became a massive hit. Dylan himself preferred the cover, and he began to mold his own live performances after Hendrix’s version. Indeed, in a September 1995 interview with the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel, Dylan said, “It overwhelmed me, really. He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn't think of finding in there. He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took license with the song from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day.”

Here rendered in the author’s own hand, the enigmatic lyrics of one of his greatest hits have long been a locus of inquiry into the Dylan’s mind and artistic process.

REFERENCE:

Clinton Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, New York: William Morrow, 2001; Jonathan Cott (ed.), Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews, New York: Wenner Books, 2006

You May Also Like

![Complete Cycle of Haftarot (Prophetic Readings), [Spain, 14th century]](https://dam.sothebys.com/dam/image/lot/21c5a5f1-1a12-40c9-a8f1-ff1c55cb81fa/primary/extra_small)