Property from an American Private Collection

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

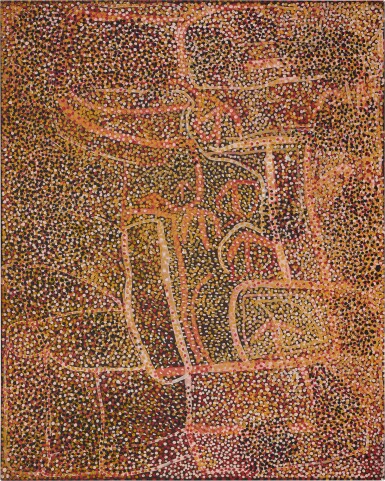

Alhalkere - Old Man Emu with Babies, 1989

Auction Closed

May 25, 09:41 PM GMT

Estimate

500,000 - 800,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from an American Private Collection

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Circa 1910 - 1996

Alhalkere - Old Man Emu with Babies, 1989

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

bears artist's name, title, Delmore Gallery catalogue number A248, and 1998 retrospective gallery label on the reverse

59 ¾ in by 48 in (152 cm by 122 cm)

Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1989

Sotheby's, Melbourne, Important Aboriginal Art, 29 June 1998, lot 36

American Private Collection, acquired at the above auction

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Crossroads - Towards a New Reality: Aboriginal Art from Australia, 22 September - 8 November 1992; additional venue: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 17 November - 20 December 1992

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Alkalkere - Paintings from Utopia, 20 February - 13 April 1998; additional venues: The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 15 May - 19 July 1998; The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 8 September - 22 November 1998

Takeo Uchiyama, ed., Crossroads - Towards a New Reality: Aboriginal Art from Australia, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 1992, p. 94, cat. no. 76

Margo Neale, et al., Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Alhalkere: Paintings from Utopia, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1998, p. 48, pl. 28, cat. no. 48

Susan McCulloch, Contemporary Aboriginal Art: A Guide to the Rebirth of an Ancient Culture, McCulloch and McCulloch Australian Art Books, Sydney, 2001, pp. 88-89

During the earliest years of Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s phenomenal painting career, the theme of the ancestral Emu (Ankerr) from Alhalkere is a recurring motif. It is particularly prominent in the Delmore Gallery commissions following their Utopia start-up in mid-1989 and continues to appear in works with their provenance well into the 1990s. When Kngwarreye painted Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies in August 1989, she had already been working between two agents, CAAMA1 and Delmore,2 for several months. This expansion of her agency had importantly increased Kngwarreye’s access to painting materials and the next seven years are prolific evidence that more painting was what she wanted to do—until the very end of her life.

One interesting effect of Kngwarreye’s new mid-year arrangement was an element of creative crossover—points at which her aesthetic preoccupations in painting for one agent sometimes intermeshed with the other. A close connection between the two streams of work could be seen in the compelling juxtaposition of Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies, painted in August, hung side by side with its close contemporary, the circular September painting, Awelye, in the 1998 Queensland Art Gallery retrospective.3

Compared with the flow of work in subsequent years, Kngwarreye’s output in her first full year of painting on canvas was quite modest. Works from 1989 are scarce and many are already in private or institutional collections. Even so, the small pool of work Kngwarreye did produce in 1989 is a reservoir of immense interest in terms of both her creative practice then and the extraordinary body of work that would follow. In mid-year, in the so-called ‘seed’ paintings, one can see the beginning of her interest in exploring thematic sequences, working in ‘series’, which becomes a feature of her later oeuvre. On the whole, however, 1989 is a year of singular, revolutionary works, the most accomplished of them being magnificent one-offs—paintings of the calibre of Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies. Kngwarreye, right from the start, revealed herself to be an entirely original, unconventional and innovative artist.

A number of key works from this period testify to the creative potency of the theme of the Emu (Ankerr) in Kngwarreye’s early oeuvre. Her first show-stopping painting on canvas—painted in December 1988 for the CAAMA Summer Project—was titled Emu Woman. This experimental project with paint and canvas was transformational in the careers of many Utopia artists, but none more so than Kngwarreye. Six months earlier, Emu Story had been Kngwarreye’s contribution to the major batik survey Utopia. A Picture Story. With both project themes firmly focussed on each artist’s patrilineal country, Emu was the Alhalkere story that Kngwarreye chose to represent. Later, other Alhalkere stories, principally centred on the motif of the Yam, appear to supplant the Emu—but this is also a period when, for Kngwarreye, painting itself becomes the story and her subject, as she declared it: the whole lot, everything. Thus, the Emu is always present in Kngwarreye’s Alhalkere paintings.

The title of the painting alludes to an important origin story belonging to the custodians of Alhalkere, the place known as country, where Kngwarreye spent her childhood. It was here at Alhalkere that the mythic Emu and his brothers emerged as central protagonists in its creation. Their foundational deeds and journeys continue to be celebrated in Anmatyerre ceremonies, song cycles, stories and paintings. As a senior custodian and ritual leader for Alhalkere, Kngwarreye took on a prominent role in awelye, the ceremonial world of women—a role that also defined her as a painter. As with so many of the titles ascribed to her paintings, Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies is most likely a distillation of what Kngwarreye said when she delivered the painting to her Delmore agents. However, the title possesses a degree of quaintness in English (the artist’s second language) that belies the gravitas and visual sophistication of what is a complex and intriguing image.

To say that the ‘story’ of the Alhalkere Emu Ancestor provided Kngwarreye with a rich vein of visual material understates her creative capacity to explore it in painting. While her status as a law woman signalled knowledge of and authority over certain formal aspects of the Emu story, as an artist she seized the day in unexpectedly creative ways. Selectively painting the ‘everywhen’ of the Emu story, Kngwarreye’s visual focus shifts between the ritual, symbolic and the prosaic aspects of her subject—or so it seems to an outsider. There are paintings in which the ceremonial body paint designs for the Emu are depicted with the discipline of a ritual specialist and others where she paints the abundance of the Emu’s favourite food Intekwe [Scaevola parvifolia]—seemingly with the passion of a naturalist and the responsive eye of an impressionist. Kngwarreye’s Emu story paintings are typically earthbound action scenes, pulsating with tracks, plant life, waterholes and curvilinear grids.

Against an array of Emu-themed works from this early period, Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies is a rare and distinctive painting. In it, Kngwarreye shifts focus from the diurnal round of the Emu, rendering instead an eerie scene of quietude and drift—drawing the viewer into a floating world of space-time, of presence and infinity, in which the linear architecture of the scene seems suspended. Even the curiously placed emu tracks, their arrow-shaped footprints, do not seem quite grounded.

In this period, new ways of painting lines and dots are always evolving and no two works by Kngwarreye are the same. However, many aspects of Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies—such as the variety of shape and colour in the dotting and her evanescent linear grids—can be seen in other closely contemporary works. This painting displays an unusual focus on careful drawing evident in the smooth curves of the grid lines as they navigate the lower corner and side of her canvas. The expressive, open relation between dots and lines Kngwarreye creates here is quite opposite to the majority of her mid-year paintings in which all the linear elements were blanketed under a dense surface of dots. Here lines stand out, articulating the different zones that Kngwarreye maps onto the canvas—some executed deliberatively, using thick and thin lines. Inside a number of these carefully drawn outlines are other zones that appear to be marked out for a special purpose.

All these details, some of which may appear decorative, are intended and significant to Kngwarreye. Of conspicuous interest is the attenuated curved line drawn along and around an (invisible) central axis. One of these curves harbours a single arrow-shape emu track, the locale of the footprint perhaps signalling the ancestral aura of the scene. Similar curved motifs occur in the iconography of other Utopia paintings of the period, notably works by Lily Sandover Kngwarreye, although these are often lined with rows of U shapes. This suggests that we are looking at icons representing shelters being used by women conducting ceremonies. If that is the case, and if Kngwarreye is also mapping a ceremonial ground in this painting, she has elected to leave such literal iconography out of the picture: the conceptual terrain of Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and His Babies is more layered and resonant, less a visual description of an event and more like a profound meditation on its meaning.

The late Gabrielle Pizzi, doyenne of early Aboriginal art gallerists, signalled the value and virtuosity of the painting by acquiring it for her personal collection. Having selected Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies during her first buying trip to Delmore in early August 1989, it appears that she held it over for her first solo show: Paintings by Emily Kame Kngwarreye the following year [June 1990], bypassing the group Utopia show she mounted in October 1989.4 Pizzi subsequently loaned the work to two important exhibitions including Kngwarreye’s first retrospective staged in 1998 by the Queensland Art Gallery. It has been reproduced on a number of occasions in the course of which it has undergone some changes of title and date.5 Both are here correctly reinstated based on the code and the title inscribed on the verso of the canvas.

Note:

The Delmore Gallery code assigned to the painting [A248] marks the beginning of the registration system Donald and Janet Holt introduced when they established their new Utopia art business, Delmore Gallery, in mid-1989. The Delmore “A” prefix was assigned to all Utopia work commissioned in an inaugural three-month period between May and August 1989, after which each month was assigned its own letter.6 It is known that Kngwarreye painted this work Alhalkere—Old Man Emu in August,7 although exactly when—which day or days in the month—is not.

Anne M. Brody

Anne Marie Brody is a curator, researcher, and writer. Over a long career, she has developed, curated, and published collections of Aboriginal Art for the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (1980-1987), and the Perth-based private art collections of Janet Holmes à Court (1987-1995) and Kerry Stokes (1998-2010). She is currently completing a single provenance catalogue raisonné of works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

1. CAAMA is the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. CAAMA Shop and its art co-ordinator, Rodney Gooch, represented the Utopia Women’s Batik group from 1987 and initiated an experimental project with paint and canvas in December 1988. Gooch later continued as a principal commissioner for Kngwarreye when he set up his own company Mulga Bore Artists in 1991.

2. Delmore Gallery was then headquartered on Delmore Downs, a third-generation pastoral [cattle] station adjacent to the Utopia community in the Sandover region north east of Alice Springs. The proprietors of Delmore Gallery, Donald and Janet Holt, were the major commissioners of work by Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

3. Alhalkere—Old Man Emu was one of two major Delmore works [cats. 12 & 48] included in the section of the exhibition devoted to 1989. Its companion in the hang Awelye 1989 [d.118 cm] was a CAAMA commission, now in the Janet Holmes à Court Collection, Perth.

4. A painting by Lily Kngwarreye with the adjacent code A247 is cat. 20 in the Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi group exhibition of Utopia art mounted in October 1989. This artist is most likely Lily Sandover, Kngwarreye’s life-long friend, family and carer. The consecutive codes suggest that Pizzi would have seen and acquired Alhalkere—Old Man Emu and his Babies at the same time.

5. There have been several changes of date and title. Another work of the period on the same theme [Emu] was for many years known as ‘Untitled’ until The Kluge-Ruhe Museum reinstated the original title ‘Hungry Emus’ based on the original Delmore documentation.

6. After August, the remaining five months of 1989 each acquired its own letter: from B (September) through to “E” (December). In mid-1991, the Holts changed this system to a different, permanent mode of registration beginning with the last two digits of the year.

7. see J. Holt, Emily Kame Kngwarreye Paintings 1998, p. 150. The title for A248 is given there as ‘Emu Country’.

You May Also Like