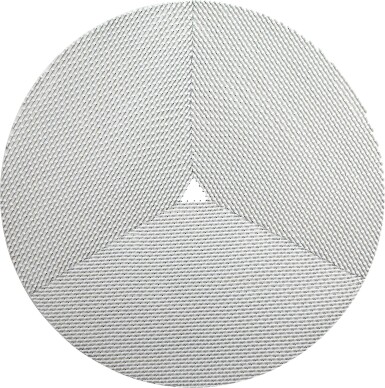

MOUNIR FATMI | QUI A BESOIN D'UN DIEU TRIANGLE #2

This lot has been withdrawn

Lot Details

Description

MOUNIR FATMI

b. 1970

QUI A BESOIN D'UN DIEU TRIANGLE #2

coaxial antenna cable, staples in Plexicase

diameter: 125cm.; 49¼in.

Executed in 2013-2014, this work is unique.

Lawrie Shabibi, Dubai

Mounir Fatmi moved to Casablanca at the age of four. He later travelled to Rome where he studied at the free school of nude drawing and engraving at the Academy of Arts, and then at the Casablanca art school, finally culminating his training at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam.

Fatmi’s oeuvre draws on memories of his childhood – of flea markets in impoverished neighbourhoods, where its vast amounts of waste and worn-out common use objects have now become objects in a figurative, museum of ruin, from which Fatmi draws. This vision also serves as a metaphor and expresses the essential aspects of his work. Influenced by the idea of defunct media and the collapse of the industrial and consumerist society, he develops a conception of the status of the work of art located somewhere between Archive and Archeology.

Fatmi's solo exhibitions include ones at the Migros Museum, Zurich; MAMCO, Geneva; Picasso Museum La Guerre et la Paix, Vallauris; AK Bank Foundation, Istanbul; Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf and at the Gothenburg Konsthall.

Fatmi’s installations were selected in several biennials including the 5th and 7th Dakar Biennales (2002 and 2006); the 5th Gwangju Biennale (2004); the 2nd Seville Biennale (2007); 52nd and 57th Venice Biennales (2007 and 2017); the 8th Sharjah Biennale (2007); the 10th Lyon Biennale (2009-10); the 5th Auckland Triennial (2013); the 10th and 11th Bamako Biennales (2015 and 2017); the 7th Shenzhen Architecture Biennale (2017-18).

Fatmi has participated in several group exhibitions including shows at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; MAXXI, Rome; Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; MMOMA, Moscow; Mathaf, Doha; Hayward Gallery, London; Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven and the Nasher Museum of Art, Durham.

Fatmi’s select institutional exhibitions include, Mamco, Geneva; Migros Museum für Gegenwarskunst, Zürich, Switzerland; Picasso Museum, war and peace, Vallauris; FRAC Alsace, Sélestat; Contemporary Art Center Le Parvis; Fondazione Collegio San Caro, Modena; AK Bank Foundation, Istanbul; Museum Kunst Palast, Duesseldorf and MMP+, Marrakesh.

He has received several prizes, including the Uriöt prize, Amsterdam; the Grand Prix Léopold Sédar Senghor at the 7th Dakar Biennale (2006), as well as the Cairo Biennale Prize (2010). He was shortlisted for the Jameel Prize of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (2013).

His work is in several notable collections including: Sindika Dokolo Foundation, Luanda; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth; Queensland Art Gallery of Australia, Brisbane; AGO, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Fondation Louis Vuitton pour la création, Paris; Fonds National d'Art Contemporain, Paris; Fonds Régional d'Art Contemporain d'Alsace, Sélestat; Fonds Municipal d'Art Contemporain, Paris; MAMC Les Abattoirs, Toulouse; Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration, Paris; Rosenblum & Friends, Paris; Foundation Frances, Senlis; FDAC L'Essonne & Château de Chamarande; Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon; Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf; Nadour, Krefeld; Written Art Foundation, Frankfurt; The Tiroche DeLeon Collection; Fondazione Cassa di risparmio di Modena, Modena; Darat al Funun, The Khalid Shoman Foundation, Amman; National Museum of Mali, Bamako; MMP+, The Marrakech Museum for Photography and Visual Arts, Marrakech; Bank Al-Maghrib, Casablanca; Wafabank Foundation, Casablanca; Museum of the ONA Foundation, Casablanca; MOCAK, Museum of Contemporary Art, Krakow; Qatar Foundation, Doha; Mathaf, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha; Jameel Foundation; King Abdulaziz Centre, Dhahran; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Rijksakademie Collection, Amsterdam; De Nederlandsche Bank N.V., Amsterdam; Miniature Museum Ria and Lex Daniels, The Hague; Kamel Lazaar Foundation, Tunis; Koč Foundation, Istanbul; The Farjam Collection, Dubai; Articulate Contemporary Art Fund, London; The Brooklyn Museum, New York and the Hessel Foundation for the Bard Museum, New York.

Fatmi lives and works between Paris and Tangier.

Who Needs a Triangular God? stresses the relativity of the representations of the divine and deconstructs the processes that underlie their elaboration. The work aims to underline the collective dimension of significations – the choice of coaxial cables insists upon the circulation of information and the connections it creates – that are essentially established according to social consensus. It also shows how a system can endlessly cultivate complexity. Its configuration experiments with the phenomena of projection at play within processes of perception by allowing the viewer to freely interpret the general composition as a simple geometric proposition or as a religious symbol. The work of art itself tends to move away from the realm of the sacred and distance itself from it, in order to better understand its mechanisms. It questions dogma, consensus and social stereotypes. It also questions our mental representations by keeping them away. It desacralizes and reveals the proportion of projections and anthropomorphism, while issuing a warning against arguments and justifications that are sometimes nothing more than ratiocinations. As for wanting to determine the nature of the divine in our societies, perhaps we should look to modern technology… “God is the greatest of shows”, says Mounir Fatmi whose work draws inspiration from Guy Debord and his writings on the consumer society.

Who Needs a Triangular God? contributes to the elaboration of an attractive esthetic with the paradoxical objective of delivering a lesson on the dangerous seductiveness of images. While the bas-relief invites the viewer to quietly receive the work’s signification, Mounir Fatmi urges him to actively reflect upon the processes that are at play in the formation of significations and mental representations.???"

Studio Fatmi, February 2017.