Property from Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, London

ANDREA BOSCOLI | TWO STUDIES OF A FLAYED MALE NUDE, AFTER PIETRO FRANCAVILLA

Lot Closed

June 25, 01:43 PM GMT

Estimate

12,000 - 18,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Property from Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, London

ANDREA BOSCOLI

Florence 1560 - 1608 Rome

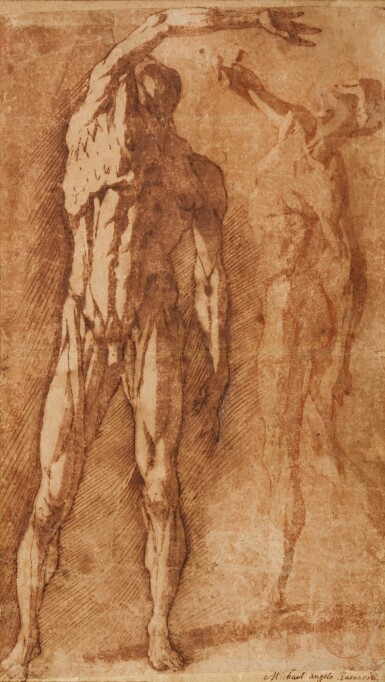

TWO STUDIES OF A FLAYED MALE NUDE, AFTER PIETRO FRANCAVILLA

pen and brown ink and brown wash, over black and red chalk;

bears old attribution, lower right: Michael angelo Buonaroti.

bears numbering and a further old attribution on the backing sheet: No.2 and Bandinelli

unframed: 406 x 236 mm.; 16 x 9⅜ in.

framed: 700 x 525 mm.; 27⅝ x 20¾ in.

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here

Comte Jean-Joseph-Marie-Anatole Marquet de Vasselot, Paris (L.2499);

His sale, ‘Collection de M. A. Marquet de Vasselot’, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 28-29 May 1891, lot 67 (as Michelangelo, ‘Deux Écorchés. Étude à la plume.’);

An unidentified collector’s mark in the form of a coat of arms indistinctly stamped in red at the lower right;

Anonymous sale, New York, Christie’s, 23 January 2002, lot 23;

Private collection.

J. Brooks, The Drawings of Andrea Boscoli (c.1560-1608), unpublished Ph.D dissertation,

University of Oxford, 1999, vol. I, p. 166 and p. 353.

"The art of draughtsmanship is, in part, all about stripping things back to basics and nowhere is this technique more literally applied than in the case of this extraordinary écorché study, by the Florentine artist Andrea Boscoli. The two flayed figures depicted here are taken from a sculpture by Pietro Francavilla and act as a delightful precursor to the dramatic écorché drawings that Peter Paul Rubens would execute a decade or so later."

Alexander Faber

Andrea Boscoli trained in the Florentine studio of Santi di Tito and was admitted into the Accademia del Disegno in 1584. He visited Rome as a young man and, like many artists before him, avidly copied the frescoes of Polidoro da Caravaggio that decorated the facades of several palaces there. Between 1582 and 1600 Boscoli worked mainly in Florence, with brief stays in Siena and Pisa. Among his earliest works is a now-lost fresco for the cloister of Santa Maria Novella and a Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, painted in 1587 for the cloister of the Florentine church of San Pier Maggiore. Boscoli was also much involved in the decorations for the apparati celebrating the marriage of the Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici to Christina of Lorraine in 1589. Between 1592 and 1594 he worked in Pisa, completing a fresco cycle for the Villa di Corliano at San Giuliano Terme, near Pisa, and an altarpiece of The Annunciation for the Chiesa del Carmine. In 1597 Boscoli painted a Visitation for the Florentine church of Sant’ Ambrogio, followed two years later by a Crucifixion for SS. Apostoli, now lost, and an altarpiece of The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist in the church of San Giovanni Battista in Rimini, signed and dated 1599. Between 1600 and 1605 Boscoli worked mainly in the Marches, painting frescoes and altarpieces for patrons and churches in Fano, Fabriano, Macerata, Fermo and elsewhere, while the last years of his career were spent between Florence and Rome. Relatively few paintings by Boscoli survive today, and it is as a draughtsman that he is best known. His drawings were highly praised by his biographer Filippo Baldinucci (who noted that ‘he drew so well...without lacking a boldness and an extraordinarily skillful touch’1) and were avidly collected. Some six hundred drawings by Boscoli are known, with significant groups in the Uffizi in Florence (many of which were once part of the extensive collection formed by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici), the Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica in Rome and the Louvre.

A large number of Andrea Boscoli’s surviving drawings, amounting to almost a third of the total, are copies after the work of other artists; indeed, more drawings of this type by him survive than by any other draughtsman of the period. Like his older contemporary Federico Zuccaro, Boscoli made numerous drawn copies after paintings and frescoes by earlier artists - including Filippino Lippi, Masaccio, Benozzo Gozzoli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Polidoro, Titian, Correggio, Andrea del Sarto and Baccio Bandinelli - as well as after antique sculpture and the works of Albrecht Dürer. Also like Zuccaro, Boscoli traveled extensively to make his copy drawings, visiting Venice, Parma, Modena and Bologna; these study trips were a means of seeing important works by other artists and learning from them. He also copied the work of a number of contemporary Florentine painters, including his teacher Santi di Tito, as well as Jacopo da Pontormo, Ludovico Cigoli, Domenico Passignano and Bernardino Poccetti. Always drawn in his own distinctive style, Boscoli’s copies are often quite free in their interpretation of the original figure or composition.

The study of human anatomy was an essential aspect of a 16th century Florentine artist’s academic training, and was accomplished mainly by the study of posed nude models in life drawing classes, as well as the occasional dissection of a cadaver for the purposes of studying the bones and musculature of the body. As one scholar has noted, however, ‘Novel study aids produced in the circle of the Accademia del Disegno further enabled artists to acquire knowledge of the human body through the process of drawing. Scorticati, figures stripped of skin, were modeled of inexpensive material (gesso, clay, or wax), with their exposed muscles alternatively flexed or relaxed depending on the positions in which they were posed. The figurines were crafted as objects of drawing exercises, some of which were apparently conducted at the academy.’2 Similarly, as another scholar has commented, ‘The infrequent availability of cadavers for study necessitated the creation of models of the flayed human form. These scorticati, usually composed of clay or wax, were fabricated for the academy’s drawing classes. The most famous and influential scorticati were those produced by the academician and sculptor Pietro Francavilla, a pupil of Giambologna, and by Cigoli…Because of their quality and utility, Francavilla’s and Cigoli’s were widely duplicated and eventually cast in bronze.’3

The present study of a flayed male figure by Boscoli is a copy of a scorticato statuette by the Franco-Flemish sculptor Pietro Francavilla (1548-1615), a pupil and assistant of Giambologna in Florence. The only extant cast of this écorché sculpture is today in the Jagiellonian University Museum in Cracow in Poland, where it has been recorded since the late 18th century.4 (Standing approximately 42 cm. high, this is one of three ecorché bronzes by or attributed to Francavilla in the collection of the Jagiellonian University Museum.) Francavilla was known to have a particular interest in anatomy, and published a treatise on the subject, entitled Il Microcosmo, accompanied by his own illustrations. As Anthea Brook has noted of Francavilla’s bronze in Cracow, ‘in this statuette the mannerist delight in the intricacies of contrapposto is taken to unusual lengths. The static poses of earlier anatomical illustrations of the 15th and 16th centuries were developed by the time of Vesalius’s Treatise (1543) into a more mannerist style, in which the bend of the heads and the gestures of the hands are expressive and pathetic. It would indeed be difficult to find a more instructive example of mannerist sculpture than the present statuette.’5 The Florentine biographer Filippo Baldinucci wrote of Francavilla that he produced a number of écorché statuettes in terracotta that were cast several times and were avidly studied by many artists.6

Boscoli produced three other large drawings after Francavilla’s scorticato statuette, from different angles. Two drawings in the Uffizi, both on blue paper, show the same figure from the right side and from the front,7 and strongly lit from the left. Monique Kornell has noted of the Uffizi drawings that ‘the evocative use of lighting, characteristic of the style of the Florentine draughtsman, matches the dramatic nature of the pose...The figure arches its back with its right arm flung across its body.’8 Another drawing by Boscoli, showing the same figure from behind and drawn on blue paper, was with Stephen Ongpin Fine Art in 2015 and is today in an American private collection.9

Boscoli’s own interest in anatomical drawings of this type finds close parallels in the similar studies of his contemporary in Florence, Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli (1559-1613). Around 1600 Cigoli produced a well-known wax model of a male écorché figure, known as Lo Scorticato (or La Notomia) and today in the Museo Bargello in Florence.10 Cigoli’s only known sculpture, the Scorticato was much celebrated in his lifetime and beyond and seems also to have been freely copied by Boscoli, in other drawings now in the Uffizi.11

In his unpublished thesis on Boscoli’s drawings, Julian Brooks commented on the artist’s ‘characteristically strong chiaroscuro’ in his ecorché drawings, and adds that they ‘seem more concerned with the general effect created by the dramatic pose and taut musculature than the intricate detail per se.’12 The Boscoli scholar Nadia Bastogi, who has noted ‘the heroic dynamism of these anatomical studies’,13 has dated these drawings to the final years of the 16th century. Although Anna Forlani Tempesti agreed with this dating,14 Brooks has suggested a slightly earlier date of c.1590-1595 for these ecorché studies, while Kornell has dated the Uffizi drawings to the late 1570s or early 1580s.15

1 ‘…disegnò sì bene...senza mancare di una franchezza e bravura di tocco straordinario’; Filippo Baldinucci, Notizie dei professori del disegno da Cimabue in qua, Florence, 1846 edition, p.76.

2 K-E. Barzman, ‘Perception, Knowledge, and the Theory of Disegno in Sixteenth-Century Florence’, in L.J. Feinberg, From Studio to Studiolo: Florentine Draftsmanship under the First Medici Grand Dukes, exh. cat., Oberlin 1991-1992, p. 42.

3 L.J. Feinberg, ‘Florentine Draftsmanship under the First Medici Grand Dukes’, in Feinberg 1991-92, p. 29.

4 C. Avery and A. Radcliffe, ed., Giambologna 1529-1608: Sculptor to the Medici, exh. cat., Edinburgh, London and Vienna, 1978-1979, p. 200, no. 194 (entry by Anthea Brook); M. Cazort, M. Kornell and K. B. Roberts, The Ingenious Machine of Nature: Four Centuries of Art and Anatomy, exh. cat., Ottawa and elsewhere, 1996-1997, reproduced p. 156, fig. 61; R. Banaszewski et al, Treasures of the Jagiellonian University, Kraków, 2000, reproduced p. 99.

5 Avery and Radcliffe, 1978-1979, p. 200, under no. 194.

6 A similar pen and ink drawing after Francavilla’s ecorché sculpture by Boscoli’s contemporary, the Florentine artist Andrea Commodi (1560-1638), is in the Uffizi (Inv. 10336 F; Feinberg, p.29, fig.31).

7 Inv. 8228 F and 8235 F; A. Forlani, ‘Andrea Boscoli’, Proporzioni, 1963, pp. 147-148, nos. 110 and 116, one illustrated pl. LXV, fig.4; Roberto Paolo Ciardi and Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, Immagini anatomiche e naturalistiche nei disegni degli Uffizi, Secc. XVI e XVII, Florence 1984, pp. 94-95, nos. 46-47, figs. 58-59; Feinberg, op.cit., one illustrated p. 29, fig. 30; Cazort, Kornell and Roberts, op.cit., pp.1 55-156, no. 43 (entry by Monique Kornell), one illustrated p.156; Nadia Bastogi, Andrea Boscoli, Florence 2008, p. 335, nos. 337-338 (one illustrated fig.382).

8 Cazort, Kornell and Roberts, ibid., p.155.

9 Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 9 July 2003, lot 18; Apollo, October 2004, p. 15 [advertisement]; C.S. Ackley, ‘The Intuitive Eye: Drawings and Paintings from the Collection of Horace Wood Brock’, in Horace Wood Brock, Martin P. Levy and Clifford S. Ackley, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, exh. cat., Boston 2009, p. 90 and p. 155, no. 87, illustrated p. 92; London, Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, op.cit., unpaginated, no.15.

10 Ciardi and Tongiorgi Tomasi, op.cit., p.91, no.41, figs.38-39. A late bronze cast after the wax original in the Bargello is illustrated in Cazort, Kornell and Roberts, op.cit., pp.239-240, no.127.

11 Inv. 8227 F, 8230 F and 8234 F; Forlani, op.cit., pp.147-148, nos.109 and 115 (not illustrated); Ciardi and Tongiorgi Tomasi, op.cit., p.95, nos.48-49, figs.60-61; Bastogi, op.cit., pp.335-336, nos.339-341 (not illustrated).

12 Brooks, op.cit., Vol.I, p.166.

13 ‘Da notare l'eroica dinamicità di questi studi anatomici, le cui pose si ritrovano anche in alcuni disegni dal modello. Lo stile grafico e la tecnica molto pittorica con l'uso della biacca e della carta cerulea, concordano con una datazione alle fine del secolo.’; Bastogi, op.cit., p.335, under no.337.

14 Forlani, op.cit., p.147, under no.110.

15 Cazort, Kornell and Roberts, op.cit., p.156.