SIDDUR (DAILY PRAYER BOOK) USED BY THE SATMAR REBBE, RABBI JOEL TEITELBAUM, IN THE BERGEN-BELSEN CONCENTRATION CAMP IN 1944

Auction Closed

December 17, 06:59 PM GMT

Estimate

100,000 - 200,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

SIDDUR (DAILY PRAYER BOOK) USED BY THE SATMAR REBBE, RABBI JOEL TEITELBAUM, IN THE BERGEN-BELSEN CONCENTRATION CAMP IN 1944

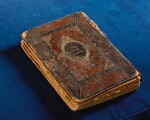

658 of 668 pages (8 1/4 x 5 3/4 in.; 208 x 145 mm) on paper (pagination: [16], ii, 36, 5-464, [24], 80, 40). Gilt-tooled morocco featuring name and place of owner (Simeon / Németi / Nyíregyháza) on upper board and year ([5]693) on lower board, bumped, scratched, and heavily worn; upper board nearly completely detached from spine and lower board detached at head; spine in five compartments with raised bands, the words siddur lettered in gilt in one of them and tefillah yesharah ve-keter nehora in another; contemporary patterned paper flyleaves and pastedowns. Accompanied by a letter on paper, comprising the Satmar Rebbe’s testimony about the provenance of the siddur.

A rare relic bearing witness to the Satmar Rebbe’s religious devotion during some of the darkest days of World War II.

Joel Teitelbaum was born in 1887, the youngest child of Hannah and Hananiah Yom Tov Lipa Teitelbaum, the latter of whom was a rabbi, yeshiva dean, and Hasidic rebbe in Máramarossziget (Yiddish: Siget). Upon his father’s passing in 1904, Joel’s older brother Hayyim Zevi succeeded to the rabbinate of Siget, while Joel and his new wife Eve Horowitz moved in with his wife’s family. Joel went on to hold rabbinic posts in Irshava and the Hasidic stronghold of Carei before eventually, in 1934, taking up the position of rabbi of Szatmárnémeti (Yiddish: Satmar), where he garnered a large, devoted following and established himself as one of the most influential ultra-Orthodox leaders in Romania and Hungary.

During the war years, Rabbi Teitelbaum remained for the most part in Satmar, but when the Nazis occupied Hungary in March 1944, close associates of his sought to smuggle him out to safety in Romania via Kolozsvár (present-day Cluj-Napoca). A botched escape attempt, however, landed him, his second wife (Faiga Schapiro), and several others in the Kolozsvár Ghetto, where he met Dr. József Fischer, president of the National Jewish Party in Transylvania and the father-in-law of Rezső (Rudolf; Hebrew: Israel) Kasztner. The latter was a leader of the Zionist movement and a member of the Budapest Relief and Rescue Committee, in which capacity he participated in high-level negotiations with Adolf Eichmann and his henchmen to transport a select number of Hungarian Jews to safety in exchange for hefty bribes. Apparently at Fischer’s request, Rabbi Teitelbaum, his wife, and his personal assistant (Ephraim Joseph Dov Ashkenazi) were granted seats on the famous Kasztner train, which left Kolozsvár on June 9, 1944, with 388 Jews aboard.

After stops in Budapest, Bratislava, Vienna, and Linz, the addition of about 1,300 more passengers, and further negotiations with the Germans, the train was nevertheless diverted to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp near Hanover, arriving on July 9. Conditions in the so-called “Hungarian camp,” a subsection of the larger complex, were much better than those in other Nazi camps, which meant that inmates could, among other things, keep some of their personal effects. Two of these inmates were the brothers Gyula (Julius; Hebrew: David Israel) and Laszlo (Hebrew: Abraham Jacob) Németi, sons of Sándor (Alexander; Hebrew: Simeon) Németi.

The elder Németi, a native of Nyírmeggyes, became a prominent lay leader in the community of Nyíregyháza (Yiddish: Niredhaz), a member of the Central Bureau of the Autonomous Orthodox Jewish Communities in Hungary, a member of the central committee of Kolel Shomre Hachomoth, and a devoted Hasid and trusted confidant of Rabbi Teitelbaum’s. In 1933, Rabbi Teitelbaum gave Németi his personal copy of Seder tefillah yesharah ve-keter nehora ha-shalem (Przemyśl: Symcha Freund, 1927-1929) as a gift. This prayer book, the original edition of which was printed in Berdychiv in 1891 or 1897 (based on an earlier version that appeared in Radyvýliv in 1820) and thereafter known as the “Berditchever siddur,” was a favorite of Rabbi Teitelbaum’s: a postwar account by Rabbi Shmuel Brach, one of the rebbe’s personal attendants, records that Rabbi Teitelbaum would pray from a copy of the Berditchever siddur with great passion and spiritual ecstasy each morning and would also make sure to consult its Keter nehora commentary (by Rabbi Aaron ben Zevi Hirsch ha-Kohen of Opatów). Moreover, the book was reprinted in Satmar in 1942—in the midst of the war—with Rabbi Teitelbaum’s approbation, in which he noted that in general it was not his practice to issue such imprimaturs, “but here I agree and declare that it is correct and appropriate to print this siddur with the aforementioned commentary, since it has already achieved acceptance among the God-fearing Orthodox […] and my father, my master and teacher, of blessed memory, also prayed from this siddur with the aforementioned commentary.”

In late May 1944, Sándor Németi and his wife Rachel (nee Roth) were deported to Auschwitz, where they, like so many other Hungarian Jews, were murdered. However, their sons Gyula and Laszlo made it onto the Kasztner transport, the former bringing with him the precious prayer book he had inherited from his father. This in itself would have been relatively unremarkable, but then, once they arrived in Bergen-Belsen, something extraordinary happened: according to Németi family testimony, the Satmar Rebbe happened to notice Sándor’s siddur—the same one that he himself had owned only eleven or so years prior—in Gyula’s possession. Because the rebbe had no prayer book of his own in the camp, he asked Gyula to borrow it; the latter naturally agreed, though on condition that the rebbe return it to him upon their liberation.

Several survivor accounts attest that the rebbe spent much of his time at Bergen-Belsen in plaintive prayer, pouring out his soul and petitioning the Creator for mercy and salvation. This was particularly clearly on display during the High Holidays, when the rebbe blew a shofar smuggled in from the Dutch part of the camp on Rosh Hashanah and led the musaf service on Yom Kippur. Many of his fellow inmates were heartened and inspired by the sight of this holy man, whose faith and religious devotion remained intact even under such trying circumstances.

Finally, in early December, the rebbe and about 1,350 fellow prisoners boarded a train headed for Switzerland. They arrived early in the morning on Thursday, December 7, corresponding to 21 Kislev, a day celebrated by Satmar Hasidim down to the present as yom ha-hatsalah ve-ha-shiharur (the day of salvation and liberation). The former inmates stopped first in St. Gallen and then traveled on to Caux, a village that is today part of the Montreux municipality. As promised, Rabbi Teitelbaum returned the siddur to Gyula Németi, for whom it not only represented an invaluable inheritance from his martyred father but also a point of connection to the revered Satmar Rebbe.

While Rabbi Teitelbaum eventually relocated first to Jerusalem and then to New York, where he successfully reestablished his Hasidic court and built it up to become one of the largest in the world, Németi apparently stayed in Montreux, marrying Charlotte Guttmann (nee Kornfein), a widow with two children, in 1949. (His brother Laszlo settled in Salzburg and another brother, Tuvyah, is buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.) About a decade later, on a return journey from a visit to Israel, Rabbi Teitelbaum stopped at the spa located near the Swiss municipalities Tarasp and Scuol (Schuls). He was met there by Gyula Németi, who requested that the rebbe record for posterity the gift he had made to Németi’s father. The following is an excerpt from the letter Rabbi Teitelbaum wrote on Wednesday, 29 Av [5]719 (September 2, 1959):

“[Let this letter serve] as proof in the hand of its bearer, the honorable, learned Mr. David Israel Németi, may his light shine—son of my friend, the honorable, learned benefactor and illustrious activist involved in charity and good works, Mr. Simeon Németi, of blessed memory, lay leader of the Holy Community of Niredhaz, may their Rock and Redeemer keep them, who was martyred in the year of the Holocaust [5]704 [1944], may God avenge his blood—that I gifted his aforementioned departed father this siddur as a memento.”

Surely, the many prayers intoned by the rebbe with much fervor and intentionality from the present siddur during that period of personal and national crisis—coupled with the book’s poignant ownership history—imbue it with great sanctity and simultaneously testify to the resilience of the Jewish spirit in the face of crushing adversity.

Provenance

1. Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum

2. Sándor Németi

3. Gyula Németi

4. Thence by descent among relatives living in Israel

Literature

Anon., Ha-ne’eman: bit’on hit’ahdut hanikhei ha-yeshivot 9,4 (77) (1957): 2.

Anon., “The Rescued,” Kasztner Memorial, available at: https://www.kasztnermemorial.com/a.html.

Hershl Friedman, Seyfer meyafeyle le-oyr godl: neys hatsole fun reben zy”a 21 kisleyv [5]705 lepak (Kiryas Joel: Di Idishe Pene, 2001), 546-549.

Solomon Jacob Gelbman, Sefer moshi‘an shel yisra’el, vol. 8 (Kiryas Joel: S. Gelbman, 2004), 251-253, 292, 301 n. 106, 345-346.

Zevi Ze’ev Wolf Goldberger, Sefer alef ze‘ira al ha-torah (Beregszász: Samuel Klein, 1929), 40a.

Motti Inbari, “How Did the Satmar Rebbe Survive the Holocaust?” The Times of Israel Blog (January 23, 2018), available at: https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/how-did-the-satmar-rebbe-survive-the-holocaust/.

Chaim Levi, “Dem rebens sider in bergen belzen,” Der yid (December 13, 2019): 16-19.

S.Y.R., “Bay di ershte sudes hoydoe—21 kisleyv shnas [5]705,” Der yid (December 15, 1995): 28.

Joseph Rapp, Sefer yosef lekah: ketubbot (Jerusalem: Ma‘yan ha-Hokhmah, 1970), introductory sponsorship pages.

Zsigmond Schwartz, “Kunteres anshei ha-shem,” in Shem ha-gedolim he-hadash (me-erets hagar) (Kleinwardein: Or Torah, 1935), 362 (no. 9), 365 (no. 38).

Moses ben Simeon Sofer, Sefer yad sofer, ed. Johanan Sofer, vol. 1 (Budapest: Ha-Ahim Gewirtz, 1949), introductory sponsorship pages.

Joel Teitelbaum, Sefer divrei yo’el: mikhtavim: kovets mikhtevei kodesh be-inyanim shonim, ed. Ephraim Joseph Dov Ashkenazi, 2 vols. (Brooklyn: Jerusalem Book Store Inc., 1980), 1:30-31 (no. 22), 2:104-105 (no. 106).

Joel Teitelbaum, Sefer iggerot maharit, ed. Abraham David Glick (Kiryas Joel: Mazzal, 2001), 120 with n. 1 (no. 126).