SEFER HA-MITSVOT (BOOK OF THE COMMANDMENTS) AND MISHNEH TORAH (HALAKHIC CODE), RABBI MOSES MAIMONIDES, VENICE: MARCO ANTONIO GIUSTINIANI, 1550-1551

Auction Closed

December 17, 06:59 PM GMT

Estimate

12,000 - 18,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

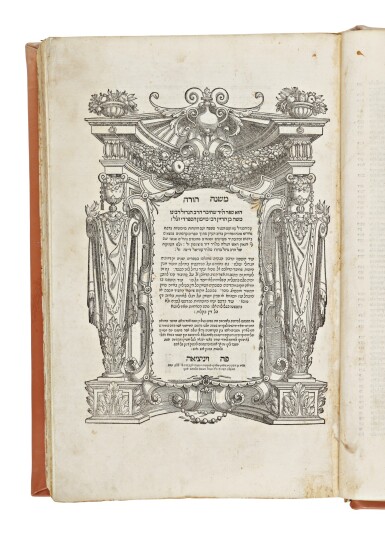

SEFER HA-MITSVOT (BOOK OF THE COMMANDMENTS) AND MISHNEH TORAH (HALAKHIC CODE), RABBI MOSES MAIMONIDES, VENICE: MARCO ANTONIO GIUSTINIANI, 1550-1551

2 parts in 3 volumes: Vol. 1 (Sefer ha-mitsvot and Sefer madda-Sefer zemannim): 272 folios (15 5/8 x 10 in.; 397 x 256 mm) (collation: i4, i-v8, vi6, i2, ii-xxviii8, xxix4) on paper; Vol. 2 (Sefer nashim-Sefer tohorah): 311 of 313 folios (15 5/8 x 10 1/4 in.; 395 x 259 mm) (collation: xxix4, xxx-xxxviii8, xxxix6 [xxxix2,7 lacking], xl-xlviii8, xlix6, l-lxvi8, lxvii5) on paper; Vol. 3 (Sefer nezikin-Sefer shofetim): 239 folios (15 1/2 x 10 1/4 in.; 395 x 261 mm) (collation: lxvii3, lxviii-xcvi8, i4) on paper. Two elaborate architectural title pages; decorative initial word panels on 1:[1r], 2v, 10r, [36v], 77r, 2:229r, 315v, 394r, 421v, 452v, 479v, 491v, 3:534v, 586v, 655r, 733v; printer’s mark featuring an image of the Temple in Jerusalem on 1:[1v], 24v, 2:title page, [390v], 3:[768v], [772r]; printed diagrams on 1:52r-v, 54v. All volumes bound in modern tan blind-tooled leather, slightly worn around edges; spines in five compartments with raised bands; title, place, and date lettered in gilt on spines; stained paper edges; modern paper flyleaves and pastedowns.

A near-complete, well-preserved copy of a controversial edition of Maimonides’ magnum opus.

Rabbi Moses Maimonides (Rambam; 1038-1204) began writing the Mishneh torah in about 1170 in response to the persecutions visited upon Jewish communities in Europe and elsewhere and the resulting decline in halakhic knowledge. The work set out to organize all the halakhic material scattered throughout the Mishnah, Tosefta, midrashim, and Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds into fourteen synthetic books (emphatically not commentaries), which were then subdivided into eighty-three treatises comprising a total of 982 chapters. This included even those laws no longer applicable in the post-Temple era, as well as those observed only in the Land of Israel—a major innovation when compared with previous halakhic compendia. Rambam titled his project Mishneh torah (lit., Repetition of the Torah), “because a person will first read the Written Torah [Bible] and later read this, and in that way he will know the entire Oral Torah without having to consult any other book in between.” Following its initial publication ca. 1180, the Mishneh torah would go on to exercise enormous influence on Jewish thought and practice, especially after Rabbis Jacob ben Asher (ca. 1270-1340) and Joseph Caro (1488-1575) elected to use it as one of the pillars upon which they structured their own vastly important halakhic codes, the Arba‘ah turim and Shulhan arukh, respectively.

The Mishneh torah was first printed circa 1473-1475 in Italy (probably Rome), then in other cities in Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, and Turkey. In 1524, the master Venetian printer Daniel Bomberg produced a beautiful, well-edited Mishneh torah in two large volumes as part of his entrepreneurial program to issue new editions of some of the most important Jewish texts: the Rabbinic Bible, the two Talmuds, and the halakhic compendia of Rabbis Isaac Alfasi, Moses of Coucy, Jacob ben Asher, and, of course, Maimonides. He intended to repeat the feat starting in 1546, but due in part to fierce competition from a rival Venetian printer, Marco Antonio Giustiniani, his hopes were frustrated and his publishing house shuttered in 1549.

In 1550, the new printing firm established by Alvise Bragadini came out with a Mishneh torah to which Maimonides’ treatise enumerating the 613 biblical commandments, known as Sefer ha-mitsvot, was appended for the first time (based on the Constantinople, ca. 1510-1525 edition). The Mishneh torah text largely mirrored, page-by-page, that of the aforementioned 1524 edition but was further edited and glossed by one of the most prominent Ashkenazic rabbis living in Italy at the time, Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen (Maharam of Padua; 1482-1565), and his son, Rabbi Samuel Judah (1521-1597). Giustiniani’s workers apparently got wind of the production of the Bragadini edition and, not to be upstaged, quickly printed their own (better edited) Sefer ha-mitsvot-cum-Mishneh torah, with a pirated version of some of Maharam of Padua’s glosses tacked on at the end. Strongly-worded introductions in Giustiniani’s two volumes cast aspersions on Maharam’s editorial work and scholarship, while a response by Bragadini toward the end of his second volume defended Maharam and his son and accused Giustiniani of trying to put him out of business and capture the market.

It seems that Maharam had made a significant investment in the Bragadini edition, and so he turned to his relative, the great halakhist Rabbi Moses Isserles (Rema; ca. 1520/1530-1572), seeking an injunction against the distribution of Giustiniani’s Mishneh torah. Rema famously ruled in Maharam’s favor, using the opportunity to compose one of the first extensive treatments of the topic of copyright in halakhic literature. Rema concluded his responsum, dated 4 Elul [5]310 (August 16, 1550), with a severe set of curses and bans against anyone “in our country” who would buy Giustiniani’s Mishneh torah instead of Bragadini’s. While it is unclear whether this particular dispute between the publishers led directly to the burning of the Talmud in Rome in early September 1553, it is not unlikely that their mutual animosity over the printing of the Mishneh torah set the stage for a future quarrel that did in fact precipitate that infamous event and its disastrous aftermath.

The present lot is a well-preserved copy of Giustiniani’s Mishneh torah, bound in three volumes. Significantly, it was owned by a member of the well-known Italian Foa family, some of whose members became printers of Hebrew books in Sabbioneta, Amsterdam, Venice, and Pisa. It also came into the possession of another important figure associated with the Italian book trade, the German Jewish antiquarian bookseller and publisher Leo Samuele Olschki (1861-1940).

Provenance

Leonis S. Olschki Bibliopolae Florentini (1:ex libris on pastedown of upper board)

Samson Meir Padua (1:[1], 3:534r, [772v])

“God’s is the land and its fullness [Ps. 24:1]. Jehiel Foa, may his Rock and Redeemer keep him, purchased this Maimuni [Mishneh torah], together with the rest of its volumes, at full price in Carpi [?] following the division that the brothers Foa divided amongst themselves. May God grant him the merit to meditate upon it – he, his descendants, and his descendants’ descendants, for all time, amen, so may it be His will. II Adar [5]312 [1552].” (1:[1], 3:534r)

“This arrived in my portion, I, Gerson ben Abraham of Padua, and I have written this so that no man come [from] outside for this, my book. Therefore, I have inscribed my name in the year 54…” (1:[1], 3:534r)

Literature

Meir Benayahu, Haskamah u-reshut bi-defusei venetsi’ah: ha-sefer ha-ivri me-et hava’ato li-defus ve-ad tseto le-or (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute; Mossad Harav Kook, 1971), 21-27.

Jacob I. Dienstag, “Mishneh torah le-ha-rambam: bibliyyogerafyah shel hotsa’ot,” in Charles Berlin (ed.), Studies in Jewish Bibliography[,] History and Literature in honor of I. Edward Kiev (New York: Ktav Publishing House, Inc., 1971), 21-108, at pp. 35-38 (no. 9).

A.M. Habermann, Ha-madpis cornelio adel kind u-beno daniyyel u-reshimat ha-sefarim she-nidpesu al yedeihem (Jerusalem: Rubin Mass, 1980), 50-60 (no. 60).

Marvin J. Heller, “Sibling Rivalry: Simultaneous Editions of Hebrew Books,” Quntres 2,1 (Winter 2011): 22-36, at pp. 22-26.

Moses Isserles, She’elot u-teshuvot (Krakow: Menahem Nahum Meisels, 1640), [18a]-22a (no. 10).

Neil W. Netanel, From Maimonides to Microsoft: The Jewish Law of Copyright Since the Birth of Print (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 71-116.

Neil W. Netanel, “Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani: The Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright,” Houston Law Review 44,4 (2007): 821-870.

Isaiah Sonne, “Tiyyulim be-historiyyah u-bibliyyogerafyah,” in Saul Lieberman (ed.), Sefer ha-yovel li-kevod alexander marx li-melot lo shiv‘im shanah (New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1950), 209-236 (Hebrew section), at pp. 211-216.

Yaakov S. Spiegel, “Mashehu al mishneh torah la-rambam mahadurot bragadin ve-yustinian,” Kiryat sefer 47,3 (June 1972): 493-501.

Vinograd, Venice 409