Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

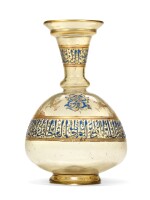

A HIGHLY IMPORTANT MAMLUK GILDED AND ENAMELLED GLASS FLASK, SYRIA, MID-13TH CENTURY

Auction Closed

October 27, 04:55 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

A HIGHLY IMPORTANT MAMLUK GILDED AND ENAMELLED GLASS FLASK, SYRIA, MID-13TH CENTURY

of squat baluster form with tall neck and flaring mouth, glass with a brownish-yellow tinge with bubbles of varying sizes, decorated with a blue enamelled inscriptive frieze to neck and body, between two gilt bands with red-outlines, shoulder with gilt split-palmette designs and blue-enamel arabesque motifs, white enamel highlights and four swimming fish, double pontil mark to underside of foot

24cm. height

Ex-private collection, France.

INSCRIPTIONS

Around the body:

‘izz li-mawlana al-sultan [filler] al-malik al-salim[?] al-‘adil al-ta’ali[?] al-sultan [filler] al-mu’ayyad al-sultan al-malik al-‘adil [filler]

‘Glory to our lord, the sultan … the king … the just … the sultan … the one supported (by God), the just king.’

Around the neck:

al-sultan al-sulta [sic] al-mu’ayyad al-islam[?] wa al-sultan

‘The sultan, the sultan, the one supported (by God) …’

This flask was conceived with an elegant but sparse scheme of gilding and enamelling that leaves much of the pale brownish glass body undecorated. A wide band of inscription in praise of an unnamed sultan encircles the centre of the vessel and a similar band is positioned around the flaring neck. The slender letters were painted first in gold and blue enamel was added afterwards so that each stroke of blue enamel is outlined in gold and in some cases overlaps the edge.

The most eye-catching and delicately rendered elements of the decoration are painted around the shoulder: two lobed arches in white enamel enclosing finely-drawn gilded foliate interlaces are symmetrically positioned on the top line of the inscription band and two more intricate scrolling interlaces in blue enamel float either side of them. Between each of these four motifs a fish, gilded and finely outlined in red enamel, swims vigorously upwards. As with the inscription, it is clear from the sometimes imprecise red lines that the artist painted the motifs first in gold, and then added the red enamel to provide visibility and definition to the overall design.

The shape of the bottle, with its pear-shaped body and flared neck, can be compared with two examples of a similar form but different dimensions. Almost identical in profile but slightly larger (H. 28.2 cm, diam. 17.8cm), is the unique bottle in the Furusiyya Arts Foundation which is largely decorated with scenes from a Christian monastery (Carboni and Whitehouse 2001, pp.242-7, no.121, fig. 1). Rather smaller (H. 17.5cm) and made of cobalt blue glass is a bottle in a private collection in Germany (Rütti 1981, p.141, no.632).

The elegantly drawn interlaces decorating the shoulder of the flask, created from stems with curving pointed leaves and trefoils which loop and cross each other, are characteristic of a group of enamelled pieces which, like this flask, probably date from around the mid-thirteenth century or a few decades later. They appear on both the previously cited flasks of the same shape, and can also be seen on the shoulder of the magnificent ‘Cavour’ vase, now in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (Carboni and Whitehouse 2001, pp.260-3, no.129). A somewhat sketchier version of the motif, reserved in gold against an enamelled blue ground and set into a pair of circular medallions, decorates the shoulders of one of the earliest datable examples of gilded and enamelled glass, a wine bottle inscribed with the name and titles of the Ayyubid ruler, Sultan al-Malik al-Nasir who ruled in Syria from 1237-60 (Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, inv. no.4261; Carboni 2001, pp.192-3, no.206). The closest comparison, however, is with a similarly sparsely decorated piece, a flared bowl on a short foot in the Royal Ontario Museum onto which, as with our flask, pairs of alternating interlace motifs are painted on a wide central band, which is otherwise left undecorated (inv. no.909.31.5; Lamm 1929, vol.2, pl.114).

Numerous glass beakers of this period, a few intact but mostly surviving in a fragmentary state, are painted with swimming fish like the ones on this bottle, always painted in gold and outlined in red. One important example is inscribed with the name and emblem of an atabeg in Mosul, Sanjar Shah (r.1180-1209). It represents the earliest datable example of enamelled and gilded glass although unfortunately its decoration is now entirely abraded and only the shadows of the fish and the inscription remain on the surface (long-term loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum; gift of John Gellatly, inv. no.1929.8.170.8; Carboni, 2001, p.189, no.198).

When filled with a clear liquid the gold would have flickered in the light, resembling the metallic scales of a fish twisting in the water. The same witty allusion was clearly intended for this bottle, which with its wide neck made a perfect container for the water that was offered to guests for hand-washing before and after meals. The typical brass ablution basin which caught the water, was often decorated on the base with shoals of swimming fish inlaid in silver and would have made a perfect companion piece.

The technical elements in evidence on this flask are all safe indicators that this vessel was produced during the Ayyubid or early Mamluk periods in one of the workshops of their capital cities. These include the chemical composition of the glass body and of the applied enamels; the light brownish colour of the glass; its texture, including a large bubble near the foot of the vessel; the ‘double’ pontil mark, meaning that the vessel was attached to a rod twice, first to help shape the flask and then to fire the gold and the enamels; and the process of designing the patterns first with gold and then superimposing the red and blue enamels for outlines, fills and highlights.

The decorative elements present on this beautifully preserved flask are all useful to place it into the fully developed, but rather early, production of enamelled and gilded glass vessels: the lightness of decoration with ample undecorated surface; the limited palette of gold, blue and red; the swimming fish; the intricate leafy motifs and cartouches; and the generic inscriptions.

The comparative objects mentioned above, some of which are datable between the late twelfth and the mid-thirteenth century, provide useful guidelines for the suggested attribution of this flask. In terms of shape, this object stands out among the most commonly produced long- and narrow-neck bottles because of its flared opening and bulge near the shoulder, the most striking comparison being with the celebrated Furusiyya bottle. While absence of evidence of similarly shaped bottles doesn’t provide evidence of absence especially in relation to glass objects, technical details such as this one can often help narrow down the location and the chronology of the glass workshop that produced the vessel. Admittedly, safely datable enamelled and gilded objects from the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods are few and far between and don’t provide an absolute timeline. However, all available evidence—both art historical and technical—points to a Syrian glass workshop toward the middle of the thirteenth century for this flask, which provides a welcome new addition to the group.

Analysis of the glass boday and enamels by Prof. Julian Henderson is consistent with a thirteenth-century Middle Eastern origin.

We are very grateful to Dr Melanie Gibson and Dr Stefano Carboni for cataloguing this lot.