Sculpture from the Collection of George Terasaki

Sculpture from the Collection of George Terasaki

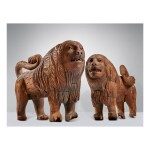

PAIR OF LIONS

Auction Closed

November 19, 09:20 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

PAIR OF LIONS

Probably Haida

Circa 1830-1860

Lion with tail to its side: Length: 41 ¾ in (106 cm); Height: 28 ¾ in (73 cm); Lion with tail curled on its back: Length: 46 ½ in (118 cm); Height: 28 ¾ in (73 cm)

Red cedar or spruce, iron nails

James Kronen Gallery, New York

George Terasaki, New York, acquired from the above in 1975

George Terasaki, advertisement, American Indian Art, Vol. 4, No. 1, Winter 1978, p. 1

Steven C. Brown, Transfigurations: North Pacific Coast Art. George Terasaki, Collector, Seattle, 2006, n.p., pl. 87 (two views)

Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse and Jisgang Nika Collison, "Gud Gii AanaaGung: Look at One Another", ab-Original, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2018, p. 278, fig. 5

“Monumental Legacy”, Native American Art, No. 23, October and November 2019, cover and p. 15

This magnificent pair of lions from the Terasaki Collection are unique masterworks, created by an artist, probably Haida, who has combined some of the classical traits of Northwest Coast sculpture with an extraordinary and unexpected choice of iconography. The remarkable subject matter reveals something of the complexity of life on the Northwest Coast in the 19th century, when the encounter between the people of the Northwest Coast and foreign visitors introduced a panoply of new images and experiences. It is the unexpected appearance of this iconography which raises the first question one might ask when looking at these extraordinary sculptures – how did a Northwest Coast artist come to sculpt a pair of lions, and how did he know what they looked like?

The question of how foreign iconography entered the sphere of Northwest Coast art has been discussed with great eloquence by the scholar Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse in several publications including, most recently, her article with the Haida scholar and curator Jisgang Nika Collison, in which these lions are illustrated. Bunn-Marcuse writes that what has been referred to, amongst other terms, as “‘Euro-American imagery’ became an integral part of Northwest Coast expression in the nineteenth century and should just be called ‘art’”, an integral part of the cultures which made it. (Bunn-Marcuse and Collison, “Gud Gii AanaaGung: Look at One Another”, ab-Original, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2018, p. 272).

There are a considerable number of Northwest Coast sculptures which depict “foreign” iconography introduced to the Northwest Coast through contact with European and American visitors; there are also several interesting examples of how foreign artworks themselves were sometimes appropriated by Northwest Coast people for their own purposes. Here we will confine these examples primarily to those found amongst the Haida, since we believe the lions are almost certainly the work of a Haida artist, as Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Bill Holm, and Steve Brown have suggested (although Brown has also considered the possibility of a Coast Tsimshian origin).

Aside from the vast canon of argillite sculptures produced principally for trade with foreign visitors (see lot 60 in this auction), there are several larger scale wood sculptures of foreign iconography by Haida artists. Amongst the most famous of these is the figure of a sphinx now in the British Museum, London (inv. no. Am1896,-.1202). This unusual but highly accomplished sculpture was made between 1874-1878 by the Haida artist Simeon Stilthda (c. 1799 – 1889), apparently based on a woodcut in an illustrated bible that was shown to him by the Anglican missionary William H. Collinson. Illustrated books, newspapers and magazines were vital sources of foreign imagery, and Bunn-Marcuse remarks that “historical photos from Haida Gwaii document that at least two houses in Old Massett [home of Sdiihldaa] - Star House and Chief Wiah’s Monster House - had collages of printed material, including newspapers” (ibid., p. 277).

Other sculptures provide a clear indication that foreign imagery was adapted to fit into the needs of existing traditions. A fascinating example of this is a highly naturalistic mask that represents, in the form of a monkey, the Tsimshian’s ba’wus, or “ground man”. The mask, collected in the early 1900s by George Emmons, is now in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, Cambridge (inv. no. 14-27-10/85877). When the museum acquired the mask in 1914 it was described as “[…] representing a mythical being found in the woods called today a monkey”. Monkeys first appeared on the Northwest Coast as seamen’s pets in the first half of the 19th century, and with their special talent for mischief, they must have immediately suggested a resemblance to the ba’wus, which although human-like is “without culture and acts in ways unacceptable to humans.” Despite its entirely foreign character, the image of the monkey was thus readily adapted to an existing masking tradition.

While the monkey, if rare, could have been seen at first hand, the source of the lion imagery in Northwest Coast art is somewhat more abstract, since it was derived from the presence of lion-like carvings on British ships, and its appearance in symbols of British heraldry such as flags and banners.

British ships historically had lion figureheads, although these had fallen out of fashion sometime before British vessels first visited the Northwest Coast, and a more likely source appears to be the “cathead” carvings which protruded over the bows of the ship, and to which the anchors were raised. These carvings take their name from the fact a lion’s head was the most popular motif carved on the end of these timbers. It is widely accepted that these catheads probably formed the model for certain Nulamal or "fool dancer" masks made by the Kwakwaka’wakw people of the Quatsino Sound region of Vancouver Island. An early example of the type, which dates to around 1830, and is particularly notable for its broadly naturalistic style, is in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum (inv. no. 91.1.27).

A small number of other works with lion iconography are recorded. Of these, the most closely related in terms of carving style is the “Lion Club” offered at Sotheby’s, New York, May 21, 2014, lot 87. In a letter to the owner of the Lion Club, Bill Holm, the eminent specialist of Northwest Coast sculpture, wrote that “I am quite in agreement that the lion club is very likely by the carver of the two lion figures [the present lot] and that the lion motif is of European derivation. […] Whether they were at one time a set is probably going to be impossible to determine, but it certainly is possible.” (Bill Holm, personal communication, April 27, 1995). Another apparently related sculpture is more enigmatic. This is an object in the collection of the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria (inv. no. 2876) which the museum identifies as a Coast Tsimshian Mask. Holm believed that this “the lion-like carving (it is not a mask) […] described as ‘found in the first Christian church in old Metlakatla’ […] is probably a ship’s carving” rather than the work of a Northwest Coast artist” (Bill Holm, personal communication, April 27, 1995). The carving style is, however, quite atypical for a ship’s cathead and we suspect that it is, in fact, Northwest Coast.

While the lion heads depicted on catheads appear to have been the source for these mask and mask-like objects, the two more sophisticated and fully in the round Terasaki sculptures, must have been based on a source which showed lions more completely, particularly when one accounts for the overall realism of the style. Certain Haida bracelets (see Bunn-Marcuse, ibid., p. 273, fig. 2 and p. 279, fig. 6) show fully realized lions, although of a somewhat more stylized and heraldic character than the more naturalistic appearance of the Terasaki lions, and of course executed on a much smaller scale. Similarly, there is a small argillite lion, posed somewhat like a sphinx, in the collection of the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria (inv. no. 15687 R). Despite their differences in scale and certain important aspects of style, these works do all share certain characteristics, and as Steve Brown notes, “the flowing manes and tufted tail tips display similarities to the European style foliate carving of some Northwest Coast silver and gold bracelets […]. The curled and pierced-through form of the tails is also not unlike some aspects of early argillite carvings, suggesting that the artist may have been a Haida carver of silver bracelets and argillite pipes or figures.” (Brown, Transfigurations: North Pacific Coast Art. George Terasaki, Collector, Seattle, 2006, n.p.).

While in all respects the Terasaki lions show themselves to be the work of a single artist, they are highly individual. Beyond certain differences in the positioning of the tail and their gait, it is in their faces that we see the most distinction. Their expressions seem to embody two distinct personalities, one perhaps more reserved, the other with a prepossessing confidence. It is interesting here to briefly consider that we can say, with some certainty, that the artist who made these sculptures never saw a lion in the flesh. The emotion he has given the sculptures was doubtless based on his observation of his fellow man, and his sensitivity in that vein must have matched his talent as an artist. He has given these sculptures an impression of deep and stirring soulfulness, the faces of the noble beasts imbued with touching humanity by the hand of man.