JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME | THE HAREM IN THE KIOSK

Auction Closed

October 22, 05:34 PM GMT

Estimate

3,000,000 - 5,000,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME

French

1824 - 1904

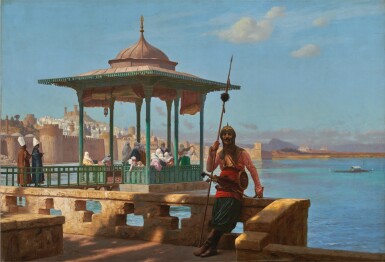

THE HAREM IN THE KIOSK

signed J.L.GEROME lower right on the wall

oil on canvas

76 by 112cm., 30 by 44in.

We are grateful to Dr Emily M. Weeks for her assistance in cataloguing this work which will be included in her revision of the artist's catalogue raisonné by Gerald M. Ackerman.

Goupil & Cie., Paris

Knoedler, New York (purchased from the above in 1880)

Jay Gould, New York (purchased from the above in 1881. Gould, 1836-1892, was a prominent railroad financier. His acquisition of the present work is indicative of Gérôme's fame in the USA during the artist's lifetime; among other contemporary American collectors were Alexander Turney Stewart, William Henry Vanderbilt, and John Taylor Johnston. His estate sale: Kende Galleries at Gimbel Brothers, New York, 12-14 November 1942, lot 594)

Maurice Alce, Flemington, New Jersey (sale: Sotheby's Parke Bernet, New York, 23 February 1968, lot 183)

Bernard K. Crawford, Montclair, New Jersey

The Fine Art Society, Ltd., London

Kurt E. Schon, Ltd., New Orleans, Louisiana

Coral Petroleum, Inc., Texas (sale: Sotheby's, New York, 22 May 1985, lot 26)

Mathaf Gallery, London

Purchased from the above

Dayton, Dayton Art Institute; Minneapolis, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Baltimore, The Walters Art Gallery, Jean Léon Gérôme, 1824-1904, 1972-73, no. 22, illustrated

London, The Fine Art Society, Ltd., Eastern Encounters: Orientalist Painters of the Nineteenth Century, 1978, no. 4

London, Royal Academy of Arts; Washington, D.C., The National Gallery of Arts, The Orientalists: Delacroix to Matisse, 1984, no. 33, illustrated in the catalogue

Sydney, The Art Gallery of New South Wales; Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Orientalism: Delacroix to Klee, 1997-98, no. 44, illustrated in the catalogue

Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique; Munich, Kunstahalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung; Marseille, Centre de la Vieille Charité, Orientalismus in Europa: Von Delacroix bis Kandinsky, 2011, no. 150, illustrated in the catalogue

Goupil stock book, vol. X, no. 14906 (as Femmes dans un Kiosque)

Knoedler stock book, vol. III, no. 3304 (as Femme dans un Kiosque)

Edward Strahan, ed., Gérôme, A Collection of the Works of J. L. Gérôme in One Hundred Photogravures, vol. 4, New York, 1881, illustrated

Possibly, Catalogue de Paris, 1883, p. 49 (as Le Harem dans le kiosque and dated v. 1870. It is likely this is the oil sketch for the present work, which was in a private collection in New York by this time.)

Fanny Field Hering, Gérôme, His Life and Works, New York, 1892, p. 241, illustrated opposite p. 252

ed. Coral Petroleum, A Near Eastern Adventure, Houston, n.d, n.p. illustrated

Lynne Thornton, Les Orientalistes: peintres voyageurs 1828-1908, Paris, 1983, p. 118, catalogued & illustrated

Gerald M. Ackerman, The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Paris, 1986, p. 97, illustrated, pp. 230-32, no. 211, catalogued & illustrated (as Harem in the Kiosk [The Guardian of the Seraglio] and dated circa 1870)

Gerald M. Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme: His Life, His Work, Paris, 1997, p. 103, catalogued & illustrated

Caroline Juler, Najd Collection of Orientalist Paintings, London, 1991, p. 133, catalogued & illustrated; p. 134, discussed

Gerald M. Ackerman, Jean-Léon Gérôme, monographie révisée, Paris, 2000, pp. 276-77, no. 211, catalogued & illustrated (and dated 1870)

Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Harems of the Mind: Passages in Western Art and Literature, New Haven and London, 2000, pp. 74 & 127, discussed, pl. 23, illustrated

Rosemary J. Barrow, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, London, 2001, p. 27, discussed, catalogued & illustrated

Lynne Thornton, Les Orientalistes: peintres voyageurs 1828-1908, Paris, 2001, p. 135, catalogued & illustrated

‘The poetry of the waning day as the landscape on the nearby shore begins to fade, the refinement of the tones of grey that veil all while revealing all, this sky and these figures all have the special charm of something exotic very carefully brought back home.’

Edmond About

Painted circa 1870-75.

This painting marks the culmination of a theme which had absorbed Gérôme for a decade. Bought by the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes before it had even been shown at the Paris Salon, The Prisoner was followed in 1869 by another Nile scene, Excursion of the Harem (fig. 1). In the present work the excursion is transposed from Egypt to Turkey, marking a bourgeoning shift in Gérôme's subjects more generally. A change of palette follows the change in setting. Rather than portray the earth tones of a sunset over the Nile, the present work depicts the blue-turquoise hues that the artist clearly associated with the waters surrounding Istanbul or the Turkish Iznik-tiled interiors that one can see in works such as Before the Audience (lot 17).

Unlike The Excursion, which features harem women in their boat, the present work arranges the ladies in several groupings beneath an Ottoman kiosk (curiously, the work may be alluding to The Excursion by including the distant boat in the background towards which the women are waving). Against this is the backdrop of a walled city on the Bosphorus or the shores of the Sea of Marmara. Under the awning of the pavilion, a group of veiled ladies and their daughters, chaperoned by the Grand Vizier and a eunuch and guarded by a formidable armed sentry, take the air. The imagined voluptuous sensuality of the harem, a favourite motif in the West’s imaginary Orient, is merely suggested here. Rather than unveil their charms, Gérôme hides the women beneath their flowing robes and veils and positions them in the background of the composition, partially obscured by the kiosk railing. Standing between us and their world is the guard, who, seemingly about to speak, scrutinises the viewer with a quizzical expression. He wears a Safavid helmet and boasts armaments including a yatagan and pistol around his waist, as well as a spear almost identical to the one carried by the rider in Riders Crossing the Desert, painted the same year (lot 12).

Since male strangers were barred from harems, artists often perpetuated the idea of harems as havens of sensual pleasure and voluptuous fantasies. However, harems were not places where hundreds of women would wait their turn to pleasure the Sultan (as Ingres notably imagined in The Turkish Bath). On the contrary, they were highly complex and hierarchical institutions. Turkey's most important harem was the Royal harem of the Seraglio. Some nineteenth century literature, as well as paintings by Osman Hamdy Bey, Alberto Pasini and others, reveal how Turkish harems of the time operated with less restrictions than one might assume. Women would enjoy outdoor walks in gardens and patios or go on excursions such as those represented in the present work. At the time, more and more Europeans recognised and admired the respectable and familial aspects of the harem. As a well-travelled man, Gérôme was surely aware of these shifting attitudes. Moreover, his experience with strict Victorian moral codes during his 1870 stay in Britain may have steered him toward a more measured and less eroticised take on the harem subject.

When Gérôme painted the present work and Excursion of the Harem, he was recalling his own trips to the Orient, specifically to Constantinople and Anatolia. He often relied on photographs taken during these trips to craft the backdrop, architecture, and costumes in the painting. Gérôme perhaps drew upon his own master Charles Gleyre’s Lost Illusions (fig. 2) in choosing to apply the overall effect of reverie—an ideal scene imbued with a melancholic restraint. Armand Silvestre seems to allude to this connection in his praise for Excursion of the Harem that can just as well describe the present work: ‘This thoroughly remarkable composition exudes an infinite calm, the calm of warm evenings over quiet waters, before the light wing of night flutteringly disturbs the polished surface of the river and fills the atmosphere with imperceptible vibrations.’ Perhaps not without irony, Paul Casimir-Périer praised Gérôme’s way of skilfully exploiting his painterly qualities: ‘The artist has again taken the course that best furthers the virtues of his painting and mostly eliminates its defects: space, water, small figures, special locations, and recollections or impressions that are personal and characteristic.’