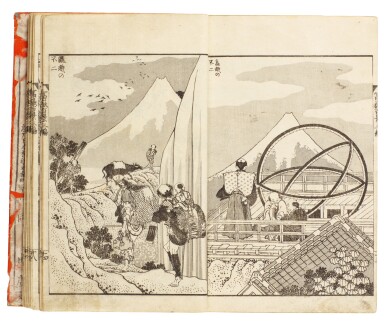

KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI (1760–1849), EDO PERIOD, 19TH CENTURY | ONE HUNDRED VIEWS OF MOUNT FUJI (FUGAKU HYAKKEI)

Auction Closed

November 5, 04:06 PM GMT

Estimate

50,000 - 70,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI (1760–1849), EDO PERIOD, 19TH CENTURY

ONE HUNDRED VIEWS OF MOUNT FUJI (FUGAKU HYAKKEI)

woodblock-printed illustrated books (3 volumes): ink on paper; 3 volumes; vols. 1 and 2 pink embossed paper covers with printed falcon-feather title slips; vol. 3 orange red paper cover with printed title slip now blue; block cutters Egawa Tomekichi (vols. 1, 2) and Egawa Sentaro (vol. 3); published in Nagoya by Eirakuya Toshiro (Tohekido) and in Edo by Kadomaruya Jinsuke, Nishimuraya Yuzo and Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudo) and others, vols. 1, 2; published in Nagoya by Eirakuya Toshiro (Tohekido) and others, vol. 3; artist’s signature zen Hokusai Iitsu aratame Gakyōrōjin Manji [Old Man Mad about Painting]; preface by Ryutei Tanehiko (1783-1842), volume 1 (1834), volume 2 (1835), volume 3 (1849?)

All vertical fukurotojibon (pouch binding)/ hanshibon:

(3)

each approx. 22.8 x 15.8 cm., 9 x 61/4 in.

Manji Hokusai at the age of seventy-five added a short autobiographical colophon in the first volume, in which he manifests a positive self-assessment and accomplishment of his long artistic career. He further expressed his aspiration to practice until the age of 110. Hokusai was determined in his belief of getting better as he grew older.

From the age of six I had a penchant for copying the form of things, and from about fifty, my pictures were frequently published; but until the age of seventy, nothing that I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish. Thus, when I reach eighty years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at ninety to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at one hundred years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at one hundred and then, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive. Those of you who live long enough, bear witness that these words of mine prove not false. Told by Gakyō Rōjin Manji (This translation from Henry Smith, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, (New York, 1999), p.7.)

He clearly saw the One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji as the beginning of a new phase in his artistic career and thereby awarded himself a new artist’s name of Manji and signed zen Hokusai Iitsu aratame Gakyōrōjin Manji [Old Man Mad about Painting]. Manji is also the same reading as the swastika (Manji), the giver of life and fortune. With this manifesto, he declares his longing for perfection and immortality. He was no longer just Iitsu Hokusai [formerly Hokusai].

The art historian Jack Hillier (1912–1995) praised the One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji as Hokusai’s “masterwork” and further states that “it [One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji] was to sum up his artistic philosophy and practice.”1 In this work, Hokusai, indeed, returned to several of the themes that had fascinated him for years, including Mount Fuji, waves, craftsmen in motion. This set of three albums depicting Mount Fuji from place to place, from various angels truly manifests the genuine and immortal effect of Hokusai.

1Jack Hillier, The Art of Hokusai in Book Illustration, (California, 1980), p. 214.

For a detailed description of each album see, Jack Hillier and F.W. Dickens, One Hundred Views of Fuji by Hokusai: Fugaku Hyaku-kei, (London, 1958).; Jack Hillier, The Art of Hokusai in Book Illustration, (California, 1980), pp. 214-225.

For a similar example in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accession no. 1997.811.1-2. go to: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/334906.