CHARLES CARYL COLEMAN | THE ANTIQUARY

Auction Closed

September 17, 04:16 PM GMT

Estimate

8,000 - 12,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

CHARLES CARYL COLEMAN

1840 - 1928

THE ANTIQUARY

signed with monogrammed initials CCC and dated 1865. (lower left)

oil on canvas

21 by 20 inches

(53.3 by 50.8 cm)

This work will be included in Adrienne Baxter Bell’s forthcoming critical study and catalogue of the works of Charles Caryl Coleman.

The artist

Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Buffalo, New York, 1866 (acquired from the above)

Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 1905

Private collection, 1961 (acquired from the above)

By descent to the present owner

New York, National Academy of Design, 40th Annual Exhibition, no. 518

Brooklyn, New York, Brooklyn Art Association, Spring Exhibition, 12th Reception, March 1866, no. 171

Buffalo, New York, Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Annual Exhibitions, 1866, no. 75; 1867-76, no. 21

"Artist Coleman Seriously Ill," The Buffalo Commercial, May 10, 1910, p. 11

"C.C. Coleman Dies; American Painter," The New York Times, December 6, 1928, p. 31

Regina Soria, Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century American Artists in Italy, 1760-1914, 1982, Rutherford, New Jersey, p. 92, illustrated p. 117

Glen B. Opitz, ed., Mantle Fielding's Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers, 1986, Poughkeepsie, New York, p. 165

We would like to thank Adrienne Baxter Bell for preparing the following essay:

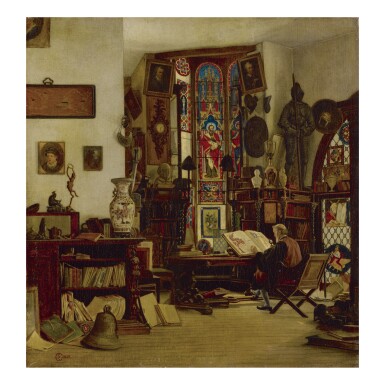

The title of this painting derives from the identity of its primary subject: the man, seated right of center, who has evidently collected the many antique objects represented. Wearing a deep-rose tunic with billowing, dark blue sleeves, Cornflower blue tights, and shoes ornamented with decorative buckles, the Antiquary examines an illuminated manuscript page with the aid of the small, circular magnifying glass in his right hand. The book before him is probably an album of dispersed leaves, as the styles of the two visible leaves are different, the left vaguely Celtic or 12th century Italian and the right evocative of fifteenth-century manuscript painting.[1] The album rests on a long, wooden, Gothic Revival library table. The three, large stained-glass lancet windows in front of him supply less light than the arched, diamond-field, leaded-glass window to his right. Superimposed on the latter are several smaller stained-glass panels. The large, squarish one shows a “horned” Moses—a reference, perhaps, to Michelangelo’s more famous sculpted version in San Pietro in Vincoli (ca. 1513-15)—displaying two stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Underneath it is a stained-glass roundel showing a haloed St. John the Evangelist, accompanied by his emblematic eagle.

The high-ceilinged room is filled to the brim with brick-à-brac. Certain items stand out. At the left, books and portfolios of papers spill from an overstuffed wooden shelving unit, the style of which is remarkably similar to the cassone in Elihu Vedder’s The Dead Alchemist (1868; Brooklyn Museum); the close friendship between Coleman and Vedder would last nearly seven decades. The bell in the left foreground is a replica, reduced in scale, of the Liberty Bell.[2] Given the pivotal date of Coleman’s painting, its inclusion surely alludes to the passing by the House of Representatives of the Thirteenth Amendment (31 January 1865), the inaugural role that Philadelphia (“First in Freedom”) took in abolishing slavery, and perhaps more generally to the liberation of the country from the bloodiest conflict on American soil. Having served as a Lieutenant for the Union cause in the Civil War, Coleman must have personally felt the impact of these historic events.

The large vase on top of the wooden shelf may be identified as a Canton export famille-rose vase in baluster form with a flaring neck and two dragon handles. Although it is loosely painted here, the original vase probably showed a courtly scene in a pavilion on a dense ground of flowering peonies. To the right, on top of another set of shelves, is a marble bust portrait of Shakespeare, a favor author of the artist; mounted on the wall above it is a cartel clock in an elaborately carved wooden frame. As a final flourish, Coleman tucked a suit of armor into the far-right corner of the room.

Given the extent and nature of the contents of this highly theatrical setting, it seems appropriate that it was once affiliated with a space deeply entwined in the theatrical history of New York.

In 1860, the stained-glass maker William Gibson acquired land on the northeast corner of Broadway and 13th street in New York for a new home for his business. According to Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, in the 1850s, the “stained-glass trade took root on or near Broadway, the primary commercial district of the city and also home to numerous churches that were built during the period and required its services”; moreover, these stained-glass panels were frequently made in the Gothic Revival style.[3] Having started one of the earliest stained-glass businesses, Gibson came to be known as “the father of glass painting” in America. He leased part of his property (844 Broadway, entrance on Broadway) to the actor/theatre manager James William Wallack (ca. 1794-1864) for the construction of a new theatre.[4] As the first performance at Wallack’s Theatre took place on 25 September 1861, the Gibson Building (at 840 Broadway, entrance on the corner of Thirteenth and Broadway) must have been completed around this time as well.[5] A photograph of the exterior of this structure, taken around 1865 and previously identified only as Wallack’s Theatre, is also clearly the Gibson Building, as we see the words “ECCLESIASTICAL GLASS & IRON” and “W. GIBSON” applied to the building’s exterior (fig. 1).

After serving in the Civil War, Coleman (1840-1928) resumed his painting career in New York. In 1865, the year he was elected an Associate at the National Academy of Design, he listed his address with the NAD as the Gibson Building.[6] The space represented in The Antiquary lies directly behind the canted stained-glass lancet windows and adjacent arched window in the photograph of Wallack’s Theatre / the Gibson Building (see arrows in fig. 1). Indeed, these lancet windows closely resemble much of Gibson’s later work, notably in Trinity Episcopal Church, Abbeville, SC, consecrated in 1860, and in Grace Episcopal Church, Amherst, MA, consecrated in 1866. In keeping with this ecclesiastical theme, the central lancet window in The Antiquary shows a haloed St. Peter holding his emblematic key in his left hand; directly below this panel, we see the Apostle Peter again, this time being crucified upside down, in a square stained-glass panel.

In 1883, Wallack’s Theatre / the Gibson Building was re-christened the Star Theatre. A number of famous actors and actresses performed there, including the great British Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928). A photograph of the building taken around 1900 shows the results of renovations; the three striking lancet windows and the small balcony above it have been replaced by a single arched window and all of the stained glass from the large arched windows on the second floor has been removed (fig. 2). The entire building was demolished in April 1901. Remarkably, the Library of Congress possesses a time-lapse film of its demise.[7] Coleman’s The Antiquary therefore preserves a small part of an extraordinary building—a landmark in the architectural, theatrical, artistic, and metropolitan history of New York and, more broadly, the history of the United States.

The identification of this painting as The Antiquary, made here for the first time, stems from two facts: first, the subject matter—evidently a man who collects and enjoys examining antiques—and second, a stamp on the reverse of the canvas that reads “Property of the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy.”

Coleman first showed a painting entitled “The Antiquary” at the National Academy of Design in 1865; at the time, he was listed as the painting’s owner. The following year, he sent the painting to the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, which included it in their annual exhibitions every year until 1876. Founded in December 1862, with former President Millard Fillmore among its incorporators, the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy thrived until 1905, when it was subsumed into the Albright Art Gallery. Coleman had been born in Buffalo; despite living abroad for much of his adult life, he maintained close ties to his home town. In the 1910s, he helped to establish the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences, which also became part of the Albright Art Gallery. When additional buildings were added in 1962, the entire structure was re-named the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. According to Vedder biographer Regina Soria, The Antiquary was deaccessioned one year before this re-identification.[8] Since then, it had been unlocated.

In the coming years, medieval subjects would figure centrally into Coleman’s body of work. While the Antiquary himself is clearly not a self-portrait—Coleman was only twenty-five years old in 1865—it may represent the man that, in a sense, he would become. After settling in Rome in January 1867, Coleman engaged deeply with the work of the Macchiaioli, including their patriotic revival of Italian history through quattrocento themes. He would paint numerous scenes of medieval musicians in medieval settings during the late 1860s and 1870s, and even as late as 1912.

Moreover, Coleman would become one of the most prodigious collectors of antiquities of his generation. Numerous visitors to his studios in Rome (at via Margutta, 33) and on Capri (Villa Narcissus) remarked on his unparalleled collections of ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, Middle Eastern, and Far Eastern objets d’art. Many of these objects appeared in his paintings. In the late 1890s and 1900s, he would become an agent for the sale of antiquities to Gilded Age collectors. Therefore, the image of the antiquarian foreshadows not only Coleman’s devotion to the quattrocento revival but also his identity as a prolific antiquities collector himself.

[1] My thanks to Roger S. Wieck, Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, Morgan Library and Museum, for advice on this issue.

[2] As with the original Liberty Bell, this one is inscribed “1751,” the year the Bell was commissioned to mark the 50th anniversary of William Penn’s 1701 Charter of Privileges, which served as Pennsylvania’s original Constitution.

[3] Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, "Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramics and Glass in New York City," in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825-1861 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), p. 351. Gibson came from a family of stained-glass makers, as his brothers John and George Gibson made the stained-glass skylights in the U.S. Capitol Dome in 1859-60. See Jean M. Farnsworth, "The Artistry of John and George Gibson and the Capitol's Spectacular Stained-Glass Skylights," The Capitol Dome 49:1 (Winter 2012): 10-18.

[4] “The New Theatre,” The New York Times (8 October 1860): 4. The Wallack family figured centrally into this history of American theatre; in fact, Wallack’s Theatre was “for more than twenty years the most famous playhouse in America.” See Arthur Hornblow, A History of Theatre in America from its Beginnings to the Present Time (Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1919), vol. II, p. 189.

[5] Hornblow, p. 192 (for the date of the first performance at Wallack’s Theatre).

[6] Maria Naylor, ed., The National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1861-1900 (New York: Kennedy Galleries, Inc., 1973), vol. I, p. 174.

[7] "Star Theatre," American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1902. Copyright: American Mutoscope & Biograph Co.; 18Apr1902; H16735; https://www.loc.gov/item/00694388.

[8] Regina Soria, Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century American Artists in Italy, 1760-1914 (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1982), p. 92.