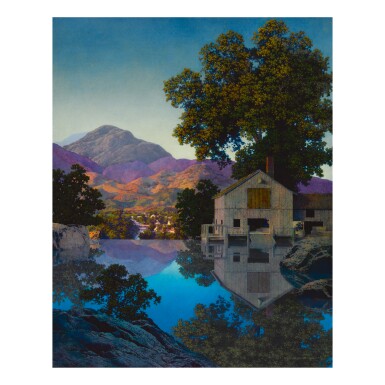

MAXFIELD PARRISH | MILL POND

Auction Closed

November 19, 04:22 PM GMT

Estimate

600,000 - 800,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

MAXFIELD PARRISH

1870 - 1966

MILL POND

signed Maxfield Parrish and dated 1945 (lower right); also signed and dated again and titled "Mill Pond" (on the reverse)

oil on Masonite

23 by 18 ½ inches

(58.4 by 47 cm)

The artist

Ralph A. Powers, Montville, Connecticut, by 1964 (acquired from the above)

[with]La Galeria, San Mateo, California

Acquired by the present owner from the above, 1974

Bennington, Vermont, Bennington College; New York, Gallery of Modern Art, Maxfield Parrish, May-July 1964, no. 36, n.p.

Brown & Bigelow Publishing Company, St. Paul, Minnesota, regular calendar, 1948

Coy Ludwig, Maxfield Parrish, New York, 1973, no. 795, pp. 184, 200, 214, illustrated pl. 57, p. 178; p. 181

Maxfield Parrish Jr., Illustrated Catalog of Painting and Sketches By Maxfield Parrish, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1973, p. 25

Alma M. Gilbert, The Maxfield Parrish Poster Book, Petaluma, California, 1989, p. 12, illustrated p. 11

Alma M. Gilbert, The Make-Believe World of Maxfield Parrish and Sue Lewin, Petaluma, California, 1990, illustrated p. 66

Alma M. Gilbert, Maxfield Parrish: The Masterworks, Berkeley, California, 1992, 1995, p. 171, illustrated fig. 8.8, p. 175

Laurence S. Cutler, Judy Goffman and The American Illustrators Gallery, Maxfield Parrish, London, 1993, p. 88, illustrated p. 89

Alma M. Gilbert, The Mechanic Who Loved to Paint: The Other Side of Maxfield Parrish, Burlingame, California, 1995, no. 53, p. 95, illustrated p. 68

Alma M. Gilbert, Maxfield Parrish: The Landscapes, Berkeley, California, 1998, pp. 17, 52, 92, illustrated p. 93

Painted in 1945, Mill Pond is one Maxfield Parrish’s of most commercially successful landscapes and among the most recognizable paintings in the artist’s oeuvre. It is listed as one of Parrish’s thirteen masterworks in Alma M. Gilbert’s publication Maxfield Parrish: The Masterworks (Berkeley, California, 1992) and was the most popular image that Parrish created for the Brown & Bigelow Publishing Company.

In 1931, at the height of his popularity in America, Parrish issued a statement to the Associated Press announcing his decision to abandon the figurative work that had made him a household name. Four years later in 1935, he signed a contract with Brown & Bigelow to provide illustrations for the company’s popular line of calendars, greeting cards, and playing cards. The agreement proved profitable for both sides—between 1936 and 1961, Parrish painted approximately 100 landscapes for the publishing company, which sold millions of calendars, three million greeting cards, and one million prints to customers worldwide.

Of the nearly 100 landscapes that Parrish produced for Brown & Bigelow, Mill Pond was the artist’s most successful. In a letter to the artist dated January 13, 1955, the publishing company’s art director Clair Fry stated: "The three pictures that stacked up the greatest volume were Millpond [sic] in 1948 number one, Shadows in 1953 number two, and Evening in 1944...The most successful pictures seem to be created around a structure of some kind that is immediately grasped at a glance...The thing that I am really sure of is that a successful picture must have strength and simplicity that catch the attention and is comprehended at a glance. This is the one factor that is evident in every successful calendar picture in our experience” (as quoted in Alma M. Gilbert, Maxfield Parrish: The Landscapes, Berkeley, California, 1998, p. 17). According to Parrish scholar Coy Ludwig, Mill Pond “had a poster-like directness and romantic setting that made it the most commercially successful calendar landscape of all those Parrish created for Brown & Bigelow” (Maxfield Parrish, New York, 1973, p. 184).

The popularity of Mill Pond is a result of Parrish’s meticulous interdisciplinary artistic process, which engaged both photography and woodworking (Fig. 1). "Parrish took a great deal of pains to ‘plan a picture’…,” explains Alma M. Gilbert, “His photographs allowed him to take the details back to the studio with him. He kept a cabinet in the studio with small compartments labeled 'Rocks,' 'Trees,' 'Streams,' etc., where he kept glass negatives of his images...In his studio machine shop, he would build elaborate balsa-wood models. A skylight was cut out over his easel so that he could throw the skylight open, lay some branches across the opening, and study their patterns and effects on the floor, in order to render a particular shading. Then he would study the models and play with light sources to obtain the right emphasis and mood. After that, he drew a pencil sketch dividing the composition, using Jay Hambidge's theory of symmetry. Sometimes a watercolor might surface; however, he preferred to sketch in oils. The final work would take the artist approximately two to three months to complete because of his meticulous glazing technique between layers of paint. This was necessary to give the works the luminosity that has remained the hallmark of Parrish's work" (Maxfield Parrish: The Landscapes, Berkeley, California, 1998, pp. 19-20).

In preparation for Mill Pond, Parrish photographed the nineteenth-century mill located in Quechee, Vermont (still extant today) and then created a model of the structure in his machine shop, which he also captured on film. Of this photograph (Fig. 2), Coy Ludwig writes: “One such interesting photograph from the artist's studio collection shows the model setup used for The Millpond [sic], published in 1948 by Brown & Bigelow. The elaborate wooden model made by the artist is seen reflected in a mirror, representing the reflection in the still water of the millpond. The model is detailed even to the tiny boards leaning against the side of the storage shed and the logs floating int he water. A silhouette of a tree painted on a sheet of paper is attached to the wall behind the model with a thumbtack. The artist created in this studio still life all the major elements of the painting. By using such models and props he was able to manipulate the scene and the lighting until he arrived at the exact effect that he wanted to paint" (Maxfield Parrish, New York, 1973, p. 200).