Property from a Private Collection

EMILY CARR | SKEDANS

Auction Closed

November 19, 04:22 PM GMT

Estimate

3,000,000 - 5,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private Collection

EMILY CARR

1871 - 1945

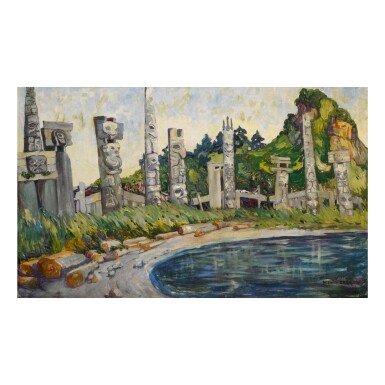

SKEDANS

signed M. EMILY CARR. (lower right)

oil on canvas

35 ¼ by 58 ¼ inches

(89.5 by 148 cm)

Painted in 1912.

The artist

David Neil Hossie, Vancouver, Canada, 1940 (acquired from the above)

Private collection, Canada (by descent)

Acquired by the present owner from the above, 1999

Vancouver, Canada, Drummond Hall, Paintings of Indian Totem Poles and Indian Life by Emily Carr, April 1913

Ottawa, Canada, National Gallery of Canada, Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art—Native and Modern, December 1927, no. 15, p. 14

Ottawa, Canada, National Gallery of Canada, Emily Carr, June-September 1990, no. 54

Kelowna, Canada, Kelowna Art Gallery, 1996

Maria Tippett, Emily Carr: A Biography, Toronto, Canada, 1979, illustrated p. 149 (in situ)

Doris Shadbolt, Emily Carr, Vancouver, Canada, 1990, p. 127

Anne Newlands, Emily Carr: An Introduction to Her Life and Art, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, 1996, illustrated p. 31 (in situ)

A.K. Prakash, Canadian Art: Selected Masters from Private Collections, Ottawa, Canada, 2003, pp. 88-89, illustrated pl. 52

Gerta Moray, Unsettling Encounters, First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr, Vancouver, Canada, 2006, pp. 7, 118-119, illustrated p. 7 (in situ)

Skedans beach was wide. Sea-drift was scattered over it. Behind the logs the ground sloped up a little to the old village site. It was smothered now under a green tangle, just one grey roof still squatted there among the bushes, and a battered row of totem poles circled the bay; many of them were mortuary poles, high with square fronts on top. The fronts were carved with totem designs of birds and beasts. The tops of the poles behind these carved fronts were hollowed out and the coffins stood, each in its hole on its end, the square front hiding it. Some of the old mortuary poles were broken and you saw skulls peeping out through the cracks.

…I went out to sketch the poles.

They were in a long straggling row the entire length of the bay and pointed this way and that; but no matter how drunken their tilt, the Haida poles never lost their dignity. They looked sadder, perhaps, when they bowed forward and more stern when they tipped back. They were bleached to a pinkish silver color and cracked by the sun, but nothing could make them mean or poor, because the Indians had put strong thought into them and had believed sincerely in what they were trying to express.

The twisted trees and high tossed driftwood hinted that Skedans could be as thoroughly fierce as she was calm. She was downright about everything.

Emily Carr, “Skedans”, Klee Wyck (the artist’s memoirs, published in 1941)

Emily Carr was a rebellious and pioneering Canadian artist who found inspiration in the forest, sea and sky of her native British Columbia, as well as the indigenous communities she encountered there. Appearing at auction for the first time in its history, Skedans is a masterpiece of the artist’s early period. Notable for its monumental scale, matched only by Yan, Queen Charlotte Islands (1912, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Fig. 1), it demonstrates the modern sensibility and artistic verve that she had acquired while studying in France, applied to the subject she loved and which would fuel her throughout her career.

Talented and determined, Carr defied convention. She was one of few female artists in the early twentieth century to reject conventional painting subjects to engage a political, spiritual and ecological dialogue. Although she did not forge deep relationships with them, remaining somewhat isolated in the Pacific Northwest, Carr’s interests ran parallel to her contemporaries’, Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo: a respected professional stature, an attachment to place and nationality, an intense connection to nature, and a strong interest in indigenous cultures. Each overcame general and individual prejudices to become her nation’s preeminent woman painter of the early twentieth century (Sharyn Rohlfsen Udell, Carr, O’Keeffe, Kahlo, Places of Their Own, New Haven, Connecticut, 2000, p. VII).

In her lifetime, Carr was often regarded as an eccentric, known in Victoria, British Columbia, for keeping a rooming house and surrounding herself with an eclectic array of animals including sheep dogs, cats, chipmunks, rats, and her Javanese monkey, Woo, for whom she made brightly colored dresses. One of five sisters, she lost her mother at the age of fourteen and her father passed only two years later, leaving her eldest sister to provide for the family. From a young age she was drawing cartoons and caricatures, and studied at the California School of Design in San Francisco, returning in 1893. By teaching art she saved money to travel to England in 1899, first studying at the Westminster School of Art, where she was disappointed by the conservative atmosphere, and then invited to St. Ives, an artist colony near Cornwall. Perhaps as a consequence of her tireless ambition, she was diagnosed with hysteria and hospitalized at East Anglican Sanatorium for over a year, finally retrieved by her sister and brought back to Canada in 1904.

Upon her return she established herself as a cartoonist, albeit an ambitious one. In 1907, she and her sister, Alice, traveled the west coast as far north as Sitka, Alaska, where she saw totem poles for the first time. To describe the journey as “intrepid” would be an understatement. Many of the remote villages were reachable only by canoe, fishing boat or trail, guided by the indigenous people with whom she stayed, or else on her own in the forest, enduring torrential rain and other challenges. This trip proved pivotal, however, as she determined to document these aboriginal villages and their totems before they were lost forever, either to nature through disintegration or removed by museums and government intervention. Returning in 1908 and 1909, she wrote:

“Whenever I could afford it I went up north, among the Indians and the woods, and forgot all about everything in the joy of those lonely places. I decided to try and make as good a representative collection of those old villages and totem poles as I could, for the love of the people and the love of the places and the love of the art; whether anybody liked them or not… I painted them to please myself in my own way, but I also stuck rigidly to the facts" (Emily Carr, Opposite Contraries: The Unknown Journals of Emily Carr and Other Writings, ed. Susan Crean, Vancouver, Canada, 2003, p. 204).

In 1910, she mounted an exhibition of the resulting works and an auction in her studio to raise money for study in Paris, then the undisputed center of the international art world. Studying with the English painter Henry Phelan Gibb, Carr was exposed to modern developments in painting and specifically to the Fauves, who expanded her palette to include bold, saturated colors and animated her brushwork. Success and praise was found as two of her paintings were accepted in the 1911 Salon d’Autumne, Autumn in France (1911, National Gallery of Canada) and Paysage (1911, Audain Art Museum, Whistler, British Columbia). These were hung alongside those of her Canadian contemporary, James Wilson Morrice, as well as influential artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse and Edouard Vuillard.

Carr was an energized, if not radicalized artist when she returned to Canada in 1912, and she immediately mounted an exhibition of her new paintings in Vancouver. The French period works, which included oils based on her earlier West Coast watercolors, were not well received or understood. Harsh criticism was launched against her, to which she responded in the city’s newspaper with characteristic defiance; a manifesto as much as an editorial:

Art is art, nature is nature, you cannot improve on it … Pictures should be inspired by nature, but made in the soul of the artist, no two individualities could behold the same thing and express it alike, either in words or in painting; it is the soul of the individual that counts. Extract the essence of your subject and paint yourself into it; forget the little petty things that don’t count; try for the bigger side.

The poor mere copyist has no chance, he is too busy worrying over the number of leaves on his tree, he forgets the big grand character of the whole, and the something that speaks … he has tried for the ‘look’ but forgotten the ‘feel’.

Contrary to my having ‘given up my inspirations’, I have only just found them, and I have tasted the joys of the new. I am a Westerner and I am going to extract all that I can to the best of my small ability out of the big glorious west. The new ideas are big and they fit this big land … I do not say mine is the only way to paint. I only say it’s the way that appeals to me; to people lacking imagination it could not appeal. With the warm kindly criticism of some of the best men in Paris still ringing in my ears, why should I bother over criticisms from those whose ideals and views have been stationary for the past twenty years?

(Emily Carr, Province, Vancouver, April 8, 1912)

Later that year, she planned another six-week trip, visiting fifteen First Nations villages, including Skedans in the Haida Gwaii (then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands), working feverishly in her new style. Unlike the ethnographic paintings of her predecessors, George Catlin and Paul Kane, Carr positioned herself within the context of her painting, evidenced in the perspective of Skedans, where she has situated her easel among the logs on the beach. As Sarah Milroy writes, “In her day, Carr’s approach to depicting Indigenous culture was distinctive in several important ways. First, she was diligent and persistent in her quest to understand. This is evident in the field sketches of totem poles, which often bear rusted thumbtack holes from when she temporarily displayed them in the villages at her workday’s end. Frequently Carr inscribed these sketches with notes on color and iconographic meaning: aesthetic delectation alone was not enough. Her early watercolors of abandoned Native villages, such as Skedans Poles, Queen Charlotte Islands (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3), stroke a studious and humble tone, offering a record not only of these sites with their monumental carvings but also her own attentive, solitary seeing” (From the Forest to the Sea, Emily Carr in British Columbia, Fredericton, Canada, 2014, p. 41).

While it is tempting to associate Carr’s choice of imagery with the “Primitivism” that was being explored by Picasso and Braque just before she arrived in France, her interests were distinctly her own. Carr brought an empathetic eye to her subject. An inquisitive outsider, she was concerned by a culture on the brink of extinction, sensitive to the perception that she was complicit in the colonization of these places. In her 1913 Lecture on Totems, she declared that “It is indeed an honor and a privilege to be taken in an Indian’s confidence… for they are and have good reason to be suspicious of the whites” adding “you must be absolutely honest and true in the depicting of a totem, for meaning is attached to every line; you must be most particular about detail and proportion. I never use the camera nor work from photos; every pole in my collection has been studied from its actual reality in its own original setting and I have, as you might term it, been personally acquainted with every pole shown here” ("Lecture on Totems," Opposite Contraries: The Unknown Journals of Emily Carr, pp. 194-195). This lecture coincided with a major exhibition of her works from this period, mounted at Drummond Hall in Vancouver. While no list of works in this exhibition is known, Skedans must certainly have been included.

With its wide panoramic format, Skedans conveys the power of this place and the wonder with which she greeted it. The overall scene is unified by expressive brushwork, and the treatment of the thoughtfully articulated totem carvings is consistent with the landscape, reasserting their spiritual connection to one another. Her palette is carefully chosen, as the weathered totems appear sun bleached through chromatic grey hues, while the tangle of growth and earth is described in brilliant, Fauve-like color. In both her earliest watercolors and her mature oils on paper from the 1930s, Carr favors a wet consistency in her paints, as seen here. This technique lends immediacy to her process and gives movement to the subject, striking a contrast to the labored impasto of her contemporaries.

When her second Vancouver exhibition failed to attract an audience, Carr had few resources and nearly abandoned painting. It wasn’t until 1927 that Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada, approached her to exhibit paintings in Ottawa at the suggestion of ethnographer Marius Barbeau, Carr sent twenty-six paintings, including Skedans (it was for this exhibition that she constructed the painting’s current frame out of found wood). This exhibition connected her to the Group of Seven for the first time and, pointedly, to Lawren Harris, who developed a deep collaborative friendship with Carr and introduced her to contemporary currents in art, both in Canada and the United States, and to Georgia O’Keeffe. This reenergized her career and led to the expressive body of work for which she is now known. By this time, the world around her had changed, and her relationship to the totems and carvings of the First Nations people became more symbolic. She returned to Skedans and painted Vanquished (1930, Vancouver Art Gallery), among others, and described what she saw:

“I had once before visited these three villages, Skedans, Tanoo and Cumshewa. The bitter-sweet of their over-whelming loneliness created a longing to return to them. The Indian had never thwarted the growth-force springing up so terrifically in them. He had but homed himself there awhile, making use of what he needed, leaving the rest as it always was. Civilization crept nearer and the Indian went to meet it, abandoning his old haunts. Then the rush of wild growth swooped and gobbled up all that was foreign to it. Rapidly it was obliterating every trace of man. Now only a few hand-hewn cedar planks and roof beams remained, moss-grown and sagging - a few totem poles, greyed and split.”

(Emily Carr, “Salt Water”, Klee Wyck, pp. 78–79)