MAHER RAIF | UNTITLED (THE FISHERWOMAN AND THE NET)

Auction Closed

October 22, 02:26 PM GMT

Estimate

40,000 - 60,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

MAHER RAIF

1926 - 1999

Egyptian

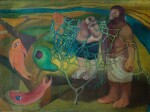

UNTITLED (THE FISHERWOMAN AND THE NET)

(ii) signed and dated 1948 in Arabic; signed and dated M. Raif.

oil on canvas, double-sided

60 by 85cm.; 23½ by 33½in.

Private Collection, Cairo

Private Collection, Greece (acquired directly from the above by the present owner in 2015)

Paris, Centre Pompidou; Dusseldorf, Kunst Sammlung; Madrid, Museo Reina Sofia;

Liverpool, Tate Liverpool, Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938 - 1948), 2016-2018

Exh. Cat., Paris, Centre Pompidou, Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938 - 1948), 2016, pp. 140-141, illustrated in colour

Mahir Raif was born in Cairo in 1926 and was part of the Contemporary Art Group, a movement that emphasized popular arts and culture and festivals as integral subjects for their art. These artists emphasized the everyday and the masses in their subject matter. They developed a style entirely their own. While Egyptian Surrealism was driven by artists who firmly believed that mimetic practice and foreign inspiration was unnecessary and at best, peripheral, the Contemporary Art Group was particularly successful in expanding a visual understanding of what constituted folkloric art. Folkloric art was expanded from being simply a window into an ontological past, to an ongoing, organic and very much, contemporary aesthetic and vessel into Egyptian modernity.

These two striking works by Maher Raif embody the power and vitality of arguably one of the most historically important social artistic movements in Egypt. Both compositionally adept through the balance of the figures created by Raif's surrealistic folkloric imagery, the artist captures peasant polity through the stylistic balance between symbolic mythology and realism.

The Contemporary Art Group came after the Art and Liberty movement. The Art and Liberty Group created an Egyptian surrealist aesthetic whose philosophical underpinnings were rooted in a defiance to fascism and a rejection of colonialism. Importantly, the Contemporary Art Group differed to these artists in so far as their preeminent concern seemed not to produce ‘defiant’ art but rather, to create work that was deeply grounded in the engagement and maneuvering of their local communities. Their interest lay more in exploring the collective conscious, as well as the subconscious ravaged by the psychological extremities of poverty, superstitions and the tragic ignorance that fatalism breeds.

Although both works allude to the fragility and struggle of the collective, stylistically, the boldness of the figures and the assuredness of their physicality lend an implicit strength to the subject matter – it is their resilience that we can draw hope from. We see this in particular, in the bodies of the fishermen, but also in the symbolism of the cave.

Specific iconography was featured often in the works of artists in the Contemporary Art Group to illustrate particular concepts or ideas. Cave iconography was referenced often in the works of this group (Abdel Hadi El Gazzar and Hamed Nada for instance) as they became representations of Sufi themes, as caves served as Sufi retreats or shelters from persecution. The suppression of the Sufis by the State resurfaced constantly in the subject matter of the Group between the 1930s and 1950s.

The book, Politics of Art in Modern Egypt references a drawing entitled, Fi-l Kahf (In the Cave) 1952 which was included in the final issue of al-Thaqafa, December 1952. The illustration implies that the location of the caves is Moqattem hills, known for its caves and Sufi retreat. This sketch bears many similarities to the work presented in this sale.

Untitled (Cave) depict bodies lying huddled in a cave – in solace and shelter. Their bald heads are accentuated which makes clear reference to their Sufi belonging and their almost fetal like positioning points to clear persecution and fear – made more impactful through the small figures hiding in baskets. The figures in the foreground are large and although one remains seated and almost folded in on himself, the Sufi standing to his right, rests his hand almost reassuringly on his head (though he rests his own head in the palm of his hand – either in calm resignation or hopeful patience). In this way, the work is not so morose and less foreboding in feeling: we are still able to feel community and strength here, in spite of deeply, trying times. The bodies are boldly defined in a style characteristic of Raif’s figurative work. However, he manages to visually paint these figures into the background of the cave. He does this through the blending of a shared coloured palette and flattened picture planes. Whether intentional or not, we can not help but draw on similarities to Edvard Munch’s iconic painting, The Scream (1893). Compositionally they are strikingly similar, but it is also the (now ubiquitous) cultural understanding of The Scream (its angst humanity’s plight) that is unavoidably brought into the fold of Raif’s depiction of this scene.

The 1940s and 1950s were characterized by a surrealist and realist visual narrative. It was only in the 1960s that the use of symbolic mythology, painted through more abstract terms, became the more prevalent style. Untitled (The Fisherwoman and the Net) was painted slightly earlier and there is no overt reference to mythological tropes, but we can perhaps still cast an allegorical net. These men are the Nile fisherman: we know this from the clear rendering of the Nile river in the background. The strength of the visual narrative is carried by its folkloric imagery: expressed through its story-telling subject matter and colour palette. The unusual, double-sided work on paper allow us to further unfold its story. In this way, Raif is able to show us in an incredibly powerful way, the delicate binary of existence, particularly one that is pulled between ‘land and sea’. The livelihoods of these fishermen moved in tandem with high and low tide – a precarious existence entirely dependent on dry or high seasons and the bounty of a catch.

On one side of the canvas, we see abundance. The vibrancy and depth of the river’s blue, mirrors plentiful return. Our fishermen appear to emerge unrestrained and ‘unshackled’ by the net – which in this instance, resembles a rooted tree, blossoming in fruitful abundance. The adroit application of colour mimics this symbology through the brown tones (of its ‘rooted’ net) that blend into deep shades of evergreen. The figures too, appear physically grounded. They stand resolute and empowered: their feet anchored in the knowledge of their bounty.

We move to another reality on the reverse side of this work. Raif depicts the same scene but uses its symbols and imagery, poignantly and powerfully, to show a life that is barren versus abundant – there is nothing implicit in our reading of an imminent metaphorical darkness and all-consuming defeat. A cast-out anchor is a visual embodiment and an antithesis to the anchored stance of the fisherman on the painting’s reverse. The river here is dull, the land barren, as seen in the brown and umber hues. Decay and desperation are also painted into the single, dark and flattened fish. The three fishermen here are swathed in what we feel is an unbreathable net, and indeed, the two less prominently illustrated fisherman are all but indistinguishable. Deeply poignant and almost evading attention is the small figure of a distant (almost forlorn looking) woman in the top left of the canvas – perhaps, this is where the work gets it pseudo-title. Its reference is to family and continued existence: a woman as a symbol that embodies it all: wife or mother – she is a symbol of home and abundant life.

Movement and colour are laden with movingly, existential readings. This works shows us a humble, simple and entirely vulnerable life, one whose tool for survival: a net, can either liberate or suffocate.

Both works are beautiful examples by an artist who was able to marry artistic prowess with the power of folkloric story telling. He created works laden with meaning, that spoke to social plight but importantly still somehow managed to visually embody a spirit of resistance and fortitude.