A head of the Prints & Multiples sale on 20 September, Alice Correia Morton looks back at the grand tradition of artists borrowing from the masters that came before them.

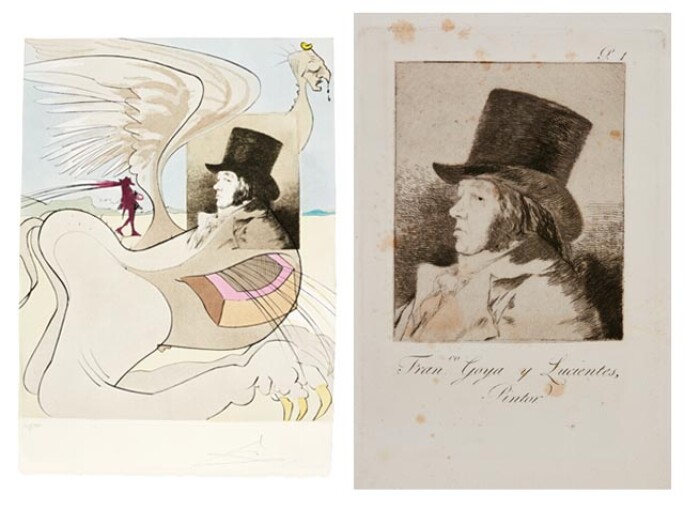

SALVADOR DALÍ, LES CAPRICES DE GOYA DE DALI (MICHLER & LÖPSINGER 848-927; FIELD PAGE 111-116). ESTIMATE: £15,000—20,000; FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE GOYA Y LUCIENTES, LOS CAPRICHOS (D. 38-117; H. 36-115). ESTIMATE: £5,000—7,000.

Since its inception the use of pre-existing images has been an important facet in the tradition of printmaking. Before today's world of the internet and photographic technology, printed reproductions of original works in other media could be used to disseminate an artist's oeuvre to a wider audience. For example, Marcantonio Raimondi (ironically well-known for being involved in one of the earliest intellectual property disputes concerning Albrecht Dürer's etchings) translated some of Raphael's drawings into engravings with a view to enhancing the artist’s reputation.

After developments in photography, publishing and an increased availability of image based communication, prints within movements such as Pop Art often used both pre-existing commercial images and photographs to create the finished work – Andy Warhol's Soup Can and his celebrity portraits being prime examples. Essentially, it is possible to broadly separate the use of pre-existing images in printmaking into two different strands: that of original designs and that of reproductive images. In the forthcoming sale, several lots use or reference earlier artworks, and sometimes even earlier prints. In doing so, their artists examine their place both within artistic traditions and specifically within the tradition of printmaking.

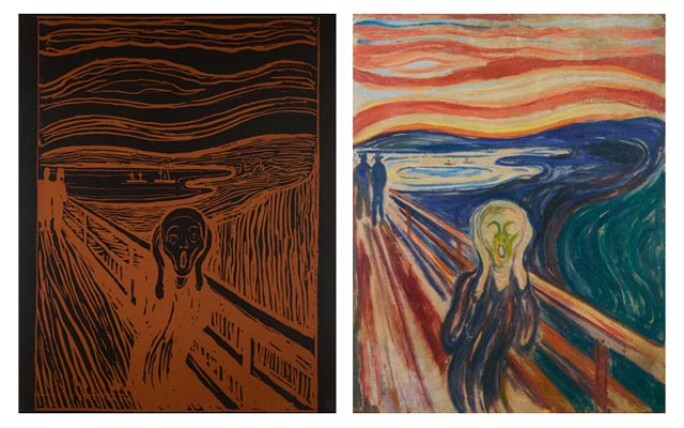

ANDY WARHOL, THE SCREAM (AFTER MUNCH, (FELDMAN & SCHELLMANN IIIA.58). ESTIMATE: 60,000—90,000; EDVARD MUNCH, THE SCREAM, 1893. COLLECTION NASJONALMUSEET, OSLO.

Salvador Dalí's Les Caprices de Goya is an excellent example of an explicit reference to an earlier work of the Western canon of printmaking. This earlier work by Goya himself, Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes Los Caprichos, is also included in the sale. Dalí's portfolio is not simply inspired by, but even makes use of images of the Spanish master's aquatints from 200 years earlier. He transforms Goya's often bizarre series into a surrealist masterpiece. The fantastical connotations of the title Los Caprichos (The Caprices) suggests Goya's favouring of imagination over reality; noticeable in the more outlandish of Goya's plates, and firmly at the forefront of Dali’s interpretation.

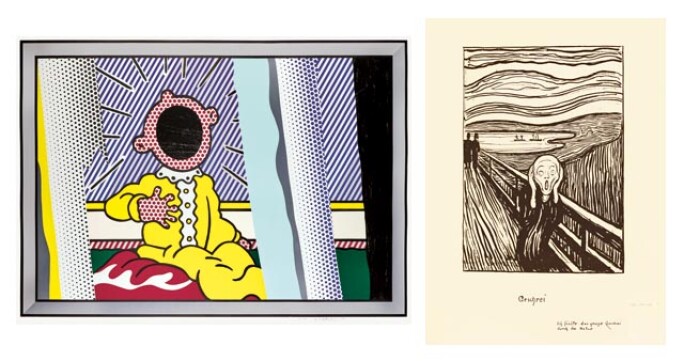

Edvard Munch's Geschrei has been designated by Gerhardt Woll as: "perhaps the most famous visual motif in the entire history of European art". Both Warhol's The Scream (After Munch) and Lichtenstein's Reflections on The Scream make reference to the work in their own creative projects. Although nearly a century apart, Warhol and Munch have a certain affinity. Behind Warhol's fashionable exterior was a shy personality perhaps not dissimilar to our impression of Munch as a rather solitary and melancholic character. Moreover, both artists were keen printmakers, enjoying experimenting with their designs. Indeed Munch, even before he made his printed versions, made his Scream in a variety of media, including paint and pastels.

ROY LICHTENSTEIN, REFLECTIONS ON THE SCREAM (C. 243). ESTIMATE: 70,000—90,000; EDVARD MUNCH, THE SCREAM. SOLD FOR: 1,805,000.

To Warhol part of the appeal of Munch's image was its iconic status. His version, though varying in colour, is compositionally close to the original. By the 1980s the imagery of many famous works of modern art had become available in the form of mass-produced posters and souvenirs. Playing with this idea of the commercialisation of fine art Warhol translated the iconography of Munch's The Scream into a Pop icon. Lichtenstein does something slightly different; he makes a tongue in cheek reference to the iconic piece though his work is visually far removed from that of Munch. By signalling his reference in the title he plays with the expectations of the viewer, encouraging an interpretation through the lens of the earlier work.

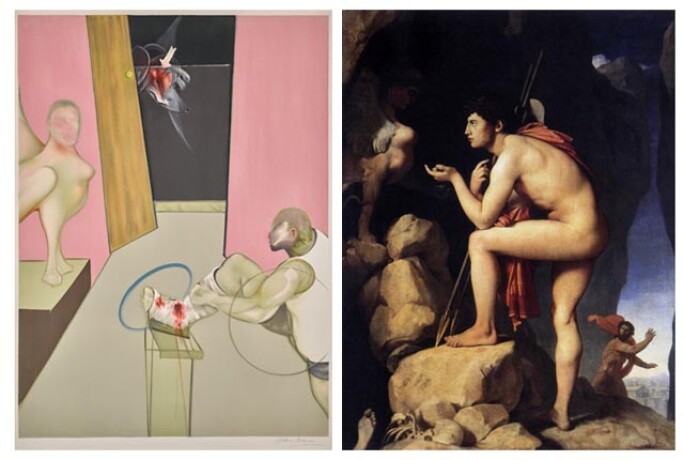

FRANCIS BACON, ŒDIPE AND THE SPHINX AFTER INGRES (SABATIER 18). ESTIMATE: 7,000—9,000; JEAN AUGUSTE DOMINIQUE INGRES, OEDIPUS AND THE SPHINX, 1827.

This approach is not dissimilar to Francis Bacon's use of Ingres' Oedipus and the Sphinx which he overtly references in his title Oedipe and the Sphinx after Ingres (Sabatier 18), acknowledging the inspiration drawn from the Neoclassical artist's three versions on the theme. It might then come as a surprise that this print ostensibly bears little in common to Ingres' aesthetic. However, the piece is alive with allusion, both to Ingres and to the literary tradition of Oedipus which inspired him. The title encourages the viewer to recognise motifs and guides interpretation of the sparse composition.

Though they do so in different ways, in referencing earlier works, each of these artists plays with the notion of the tensions between reproduction, originality, and artistic value integral to the genre of printmaking. Whilst highlighting the idea of copying and reproduction, they bring to the forefront the capacity for vitality and artistic manipulation. These prints negotiate the place of multiples between commercial printing and fine art.