‘T he point of art is to explore grey areas,’ says Louisa Macmillan, a researcher on Arab Modernism who led a panel on the relationship between traditional and modern art at Art Dubai in March, ‘And to find exceptions to every rule.’

Macmillan was speaking in the context of the Islamic Arts Biennale, the ambitious exhibition that opened in Jeddah in January 2023, with Sotheby’s as a supporting partner. The biggest exhibition of Islamic art to have been staged since the World of Islam Festival in the UK in 1976, it's situated within the Hajj Terminal of King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah, where purpose-built galleries and exhibition spaces present a curated selection of cultural, intellectual, and artistic achievements across centuries. It's a vivid, kaleidoscopic trip through centuries of art, ancient treasures, contemporary design, architecture, ceramics, sacred texts, cutting-edge multimedia installations and much more, sourced from prestigious Islamic arts collections worldwide.

It’s an intriguing proposition: What exactly constitutes an Islamic Arts Biennale? Saudi Arabia’s first biennale, the 2021 Contemporary Art Biennale at the JAX District in Diriyah, was a straightforward proposition: contemporary art works, global purview, stated curatorial thesis. But an Islamic arts biennale? Beyond ‘Islamic art’ being itself a fluid category, the idea of explicitly foregrounding religious themes within the secular context of contemporary art isn’t straightforward. Like listening to a story told by music – the Biennale’s venue brings you through the darkness of the new, purpose-built galleries for both contemporary commissions and Islamic artefacts, into expansive light, drawing you in, under the billowing tents of an airport terminal specifically built for Hajj pilgrims. One had to blink a moment to forget the beauty and think about the implications and wider context of the show.

For this is contentious territory to be wading into. Is ‘Islamic’ a geographical, chronological, or thematic marker? Or does it just mean that an artist is Muslim? Even defining ‘art’ is difficult: many scholars have argued that ‘art’, in the sense of Islamic art, is a Western construct and too narrowly visual to fully comprehend the vast sensorial and spiritual range of Islamic culture.

These questions are worth mentioning because they show that the Islamic Arts Biennale is a pretty radical proposition – and one the Diriyah Biennale Foundation has emphatically succeeded in addressing, by refusing to give stated definitions, and instead, allowing the works themselves to offer up their own interpretations.

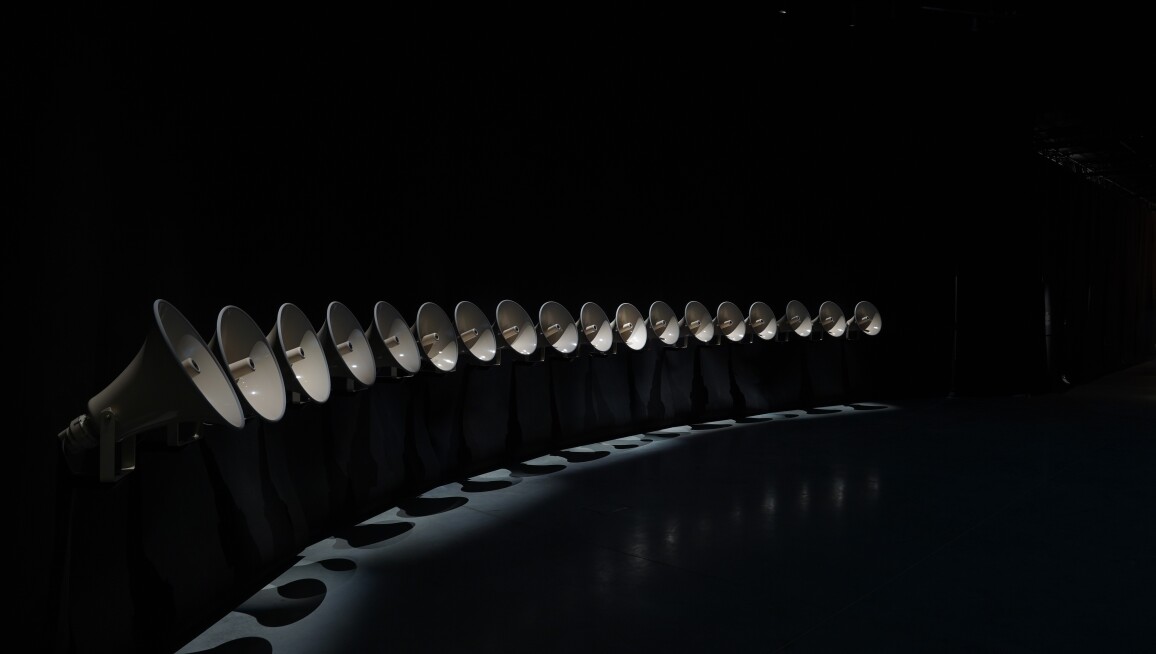

So, for instance, we encounter contemporary commissions that respond to elements of Islam, such as Joe Namy’s installation inspired by the adhan (call to prayer), that opens the show. Or, we find ourselves exploring the sense of memory and connectedness found in Bangladeshi artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin’s knotted The River Remembers (2023). Further into the exhibition and we encounter the simplicity in designating a space set apart from the ordinary world with a simple border made of rocks, in the The Last Tashahud by Moath Alofi, developed with Sumayya Vally, one of the four curators of the exhibition.

The Islamic Art Biennale juxtaposes ancient artefacts and contemporary works - another aberration from the usual biennale strategy of sticking to present-day art (albeit with increasing exceptions) - which, to me, shows a measure of confidence by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

And it’s not a confidence to be taken lightly. Saudi Arabia is an Islamic country, and the interest and the religious commitment among its general populace might mean staging an Islamic arts biennale makes more sense than a contemporary art biennale. When I was there, the visitors comprised a few groups of young Saudi Arabian women; two international KOLs (key opinion leaders, in consultant-speak) and a trio of Pakistani men in shalwar kameez, all very taken by Muhannad Shono’s sublime installation Lines in Light, Lines We Write, 2023.)

This is the second major Saudi-adjacent show I’ve seen over the past 12 months that freely mixed work from different time periods and categories (art, decorative arts, documents, and artefacts). The first was the Lyon Biennial, curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, to which the Diriyah Biennale Foundation loaned five works. Bardaouil and Fellrath used art and artefacts from the state museum collections of Lyon to engineer a mise-en-scene, about the historical relationship between the textile industry of Lyon and its markets in Beirut – acknowledging a running bass note of racism and colonialism.

The penchant of biennales towards theatricality in general tends to take place via the exhibition’s setting; think of the 2006 Berlin Biennial’s Of Mice and Men, curated by Maurizio Cattelan, Ali Subotnick, and Massimiliano Gioni, which used evocative spaces along Berlin’s Auguststraße, such as a historic former Jewish girls’ school, to create a show that ‘unfolded like a novel,’ as they said at the time. For the Islamic Art Biennale, the sheer scale of the installation conveyed a massive sense of accomplishment. As Sotheby's Mai Eldib commented, after visiting the Jeddah site of the architecture. 'I can’t even begin to express the scale, it is a magnificent space, it's very moving. There is nothing like this in terms of scale for Islamic art anywhere in the world, that combines ancient and modern. It's amazing.'

'There is nothing like this in terms of scale for Islamic art anywhere in the world, that combines ancient and modern, it's amazing'

Now the curatorial creative hand is moving to the selection of artworks itself, significantly, happening in, among other places, non-Western or post-colonial contexts. But the categories between these art forms are indeed Western constructs, and one could argue that among Saudi Arabian contemporary artists, such categories are unprecedentedly fluid, due to the still-emerging art infrastructure in Saudi Arabia.

Today, young creative Saudis are coming to fine arts having trained in a broad diversity of disciplines, such as art and architecture (Bricklab), art and design (Basmah Felemban), or art, architecture, and calligraphy (Nasser Al Salem).

The exhibition at the Islamic Arts Biennale in total, was a celebration of the beauty of Islam, from finely-woven prayer mats to the calligraphy of Qurans, and an argument that the aesthetic and spiritual value of Islam is not limited to historical documents of religion but also to realms that are coded as progressive and international, such as that of contemporary art. This sense of a recuperation of Islamic art - however one defines the category - accounted for the acclaim afforded the biennial’s reception.

‘Islamic art can be quite a dry subject,’ says Venetia Porter, the former curator of Islamic art at the British Museum. ‘I use scripts and ceramics and metalwork – but you don't ever look at the object; you don't think of them as living. What they did in the biennial was to turn them into living things. And then the contemporary pieces echoed back. It was absolutely sensational.’

Sotheby's Specialist Benedict Carter Selects his Biennale Highlights

Sotheby’s specialist Benedict Carter was on the ground at the launch of the Biennale as part of the Sotheby's team conducting guided tours and participating on panel discussions. He sent us his reactions to the Biennale and selected works on view.

‘I can’t think of a single exhibition that’s been attempted on this scale before, not at least since the 1976 World of Islam Festival in the UK. And my impression here is that everyone - from the staff at the biennale venue, the organisers, to the taxi drivers and everyone at my hotel- wanted this to work and be a success.

I heard a lot of visitors commenting on what a phenomenal undertaking and success it was.

And we had a real variety of people attending the Sotheby’s tours of Gallery 5, including a contemporary art advisor from Dubai, an artist from Kazakhstan who wanted to know about the Islamic and classical art world and of course, members of the public.

People on the tours were interested to learn about the classical Islamic pieces, to understand the other side of the Middle Eastern art world, and there was a particular interest in the birth of forms such as calligraphy and the craftsmanship, from the first centuries of Islam. There was a good mix of engaged people from different backgrounds, who were working in diverse spheres. Highlights for me included Haroon Gunn-Salie’s Amongst Men, with 1,000 cast kufiyah hats commemorating the 1969 funeral of South African Imam and activist Abdullah Haron, and beyond that was a huge bed of tombstones, dating from between the 9th and 13th centuries. Another strong piece was Moroccan artist M’barek Bouhchichi’s commission Kolona min Torab, (Everyone is from Earth), made of clay markers of various colours.

One of the most interesting perspectives for me and anyone interested in Islamic history is the exhibiting of hitherto unpublished manuscript materials from the Shrine Library in Medina. Most interesting and important amongst these finds are a group of huge bifolia from a monumental Qur’an, being seen in public for the first time at the Biennale. They are installed to maximise size and space, alongside the various contemporary art installations.

It was already a fragmentary Qur’an manuscript, so double pages are spread across various cases to emphasise the monumental size. It is huge, a metre tall – and royal quality, from the Timurid period in the early 15th century. It was endowed to the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and is a highlight of the Biennale.

Also on view is one of the greatest daggers from any culture or period, loaned from the Al Sabah collection in Kuwait, on show in Gallery 5. It stems from the early 17th century, from the period of the great Mughal emperor Jahangir. The scabbard and the hilt displays 1600 rubies and 2000 gemstones altogether. It’s a fantastically sumptuous royal piece, made for an emperor.

A pair of two carved marble columns from the 8th century were also a talking point of the Biennale. Displayed alongside a spectacular set of doors from the Ka’ba itself, the two marble columns have never been seen in public before and have real impact in the setting. They are inscribed from “the people of Kufa” in Iraq, and either made by itinerant Iraqi craftsmen working in the Hijaz - or actually shipped from Kufa itself as an endowment to Mecca. They are pretty spectacular works.

A pair of Ka’ba doors from the 17th century in the Mecca pavilion are fabulous – with centuries of wear giving them a real presence and patina. And the inclusion of a 20th-century Qur’an written in Braille was also fascinating. These are just a few of the things, in my view, that make the Biennale exceptional.