Leonard A. Lauder, Collector

Gustav Klimt

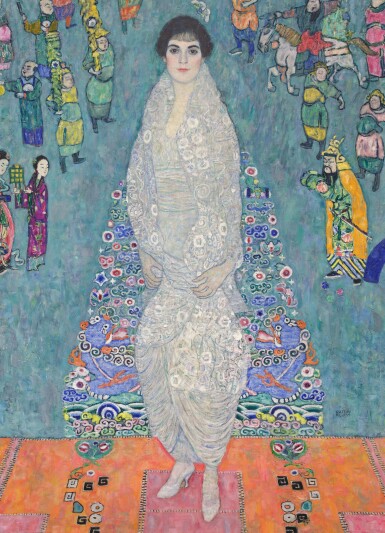

Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer)

Auction Closed

November 19, 12:41 AM GMT

Estimate

Upon Request

Lot Details

Description

Leonard A. Lauder, Collector

Gustav Klimt

(1862 - 1918)

Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer)

signed Gustav Klimt (toward lower right)

oil on canvas

71 by 51 ⅜ in. 180.4 by 130.5 cm.

Executed in 1914-16.

August and Serena Lederer, Vienna (commissioned from the artist in 1914 and acquired in 1916)

Impounded in situ at Bartensteingasse 8 by Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz, 26 November 1938

Seized by Landesgericht Wien and deposited at Kirchner & Co, Vienna, 10 December 1939

Termination of seizure, 30 September 1948

Restituted to Erich Lederer, Geneva in 1948 (son of Serena Lederer and brother of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, née Lederer)

Serge Sabarsky Gallery, New York (acquired from the above by 1983)

Acquired from the above in December 1985 by the present owner

Stockholm, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Österrikiska Konstutställningen, 1917, no. 104, p. 15 (titled Porträtt, fru L.)

(possibly) Vienna, Verein der Museumsfreunde, Ausstellung von Erwerbungen und Widmungen zu Gunsten der öffentlichen Sammlungen des Vereins der Museumsfreunde Wien 1912–1936 sowie von Kunstwerken aus Privatbesitz, 1936, no. 2, p. 8 (titled Junges Mädchen)

New York, Museum of Modern Art, Vienna 1900: Art,

Architecture and Design, 1986, p. 160; p. 204, illustrated in color (titled Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated 1914)

Vienna, Belvedere, Klimt’s Women, 2000-01, pp. 59, 63 and 133-34; p. 132, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

New York, Neue Galerie, New Worlds: German and Austrian Art, 1890-1940, 2001-02, no. I.14, p. 65, illustrated in color; p. 127 (titled Bildnis Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

New York, Neue Galerie and Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Viennese Silver: Modernist Design 1780-1918, 2003-04

New York, Neue Galerie, Birth of the Modern, Style and Identity in Vienna 1900, 2011, no. 62, p. 158, illustrated in color; p. 279 (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

New York, Neue Galerie, Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900-1918, 2016-17, n.n., pp. 56, 68 and 139, illustrated in color; pp. 57 and 141, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room); pp. 58, 60-61, 63, 65-67, 70-78, 138 and 140; p. 62, illustrated (in installation photograph of Stockholm, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Österrikiska Konstutställningen, 1917); p. 69, illustrated (detail); p. 70, illustrated in color (detail)

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, 2017-2025 (long term loan)

Max Eisler, Gustav Klimt, Vienna, 1921, p. 49

Max Eisler, ed., Gustav Klimt, Eine Nachlese, Vienna, 1931, p. 16; pl. 22, illustrated in color (titled Bildnis Baronin Bachofen-Echt)

“Gustav Klimt,” Moderne Welt, vol. 32, no. 3, December 1931, p. 13, illustrated (titled Baronin Bachofen)

Ingomar Hatle, Gustav Klimt, ein Wiener Maler des Jugendstils, Dissertation, Universität Graz, 1955, pp. 98 and 99; pl. 116, illustrated (titled Bildnis der Baronin Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1915)

Emil Pirchan, Gustav Klimt, Vienna, 1956, p. 47; pl. 100, illustrated (titled Porträt Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Exh. Cat., Vienna, Galerie Christian M. Nebehay, Gustav Klimt: Eine Nachlese, 1963, n.p., illustrated (titled Porträt Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1910)

Fritz Novotny and Johannes Dobai, Gustav Klimt, with a Catalogue Raisonné of His Paintings, Boston, 1968, no. 188, pp. 39 and 45; pl. 92, illustrated in color; p. 360, illustrated (titled Bildnis Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Christian M. Nebehay, ed., Gustav Klimt: Dokumentation, Vienna, 1969, no. 596, pl. II, illustrated (detail); pl. VII, illustrated in color (detail); p. 467; p. 469, illustrated (titled Bildnis Baronin Bachofen-Echt (Tochter von S. Lederer) and dated circa 1914)

Alice Strobl, Gustav Klimt. Drawings and Paintings, Salzburg, 1973, pl. 70, illustrated in color; p. 119 (titled Portrait of the Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1912)

Alessandra Comini, Gustav Klimt, New York, 1975, p. 30; pl. 12, illustrated in color (titled Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

British Museum, ed., The Classical Tradition, London, 1976, p. 282 (dated 1914-15)

Johannes Dobai, L’Opera completa di Klimt, Milan, 1978, no. 174, p. 16; pl. LVI, illustrated in color; p. 108, illustrated (titled Ritratto della Baronessa Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Maly and Dietfried Gerhardus, Symbolism and Art Nouveau, Oxford, 1979, no. 25, pp. 9 and 56, illustrated in color and illustrated in color on the back cover (titled Portrait of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Exh. Cat., New York, Galerie St. Etienne, Gustav Klimt Egon Schiele, 1980, p. 27

Alice Strobl, Gustav Klimt: Die Zeichnungen, vol. III, Salzburg, 1984, pp. 91, 93-94 and 96; p. 92, illustrated; vol. IV, p. 192 (titled Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer and dated 1916)

Christian Nebehay, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele und die Familie Lederer, Bern, 1987, pp. 26 and 29; p. 27, illustrated in color (titled Porträt Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, Schwester von Erich Lederer and dated 1914)

Steven Beller, Vienna and the Jews, 1867-1938: A Cultural History, Cambridge, 1989, p. 28

Jane Kallir, Gustav Klimt: 25 Masterworks, New York, 1989, pl. 21, p. 52; p. 53, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of the Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914-16)

Gerbert Frodl, Klimt, London, 1992, no. 2, p. 155, illustrated (titled Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Gilles Néret, Gustav Klimt, 1862-1918, Cologne, 1992, pp. 68 and 95; p. 80, illustrated in color (titled Bildnis Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Christian M. Nebehay, Gustav Klimt: From Drawing to Painting, London and New York, 1994, no. 240, p. 203, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Catherine Dean, Klimt, London, 1996, fig. 14, pp. 21 and 30; p. 23, illustrated (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Exh. Cat., Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Gustav Klimt: Modernism in the Making, 2001, fig. 197, p. 210, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Claude Cernuschi, Re/Casting Kokoschka: Ethics and Aesthetics, Epistemology and Politics in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna, Madison, Teaneck and London, 2002, p. 129

Exh. Cat., Vienna, Belvedere and Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Gustav Klimt Landscapes, 2002-03, pp. 41 and 43; p. 206, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room) (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Sophie Lillie, Was einmal war: Handbuch der enteigneten Kunstsammlungen Wiens, Vienna, 2003, pp. 145 and 1245

Tobias G. Natter, Die Welt von Klimt, Schiele und Kokoschka. Sammler und Mäzene, Cologne, 2003, pp. 121-22, 124 and 135; p. 123, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room); p. 125, illustrated in color (titled Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer)

Rainer Metzger, Gustav Klimt Drawings & Watercolors, New York, 2005, no. 236, p. 308, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Christian Brandstätter, ed., Vienna 1900 and the Heroes of Modernism, London, 2006, p. 105, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Exh. Cat., Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum and New York, Neue Galerie, Vincent van Gogh and Expressionism, 2006-07, p. 107; p. 108, illustrated in color (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Alfred Weidinger, ed., Gustav Klimt, New York, 2007, no. 227, p. 226; p. 300, illustrated in color; p. 301, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room)

Exh. Cat., New York, Neue Galerie, Gustav Klimt: The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, 2007-08, no. 23, fig. 15, pp. 56, 60, 64 and 83; pp. 25 and 65, illustrated in color; p. 65, illustrated (in a photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room) (titled Portrait of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Exh. Cat., Liverpool, Tate Gallery, Gustav Klimt Painting, Design and Modern Life in Vienna, 2008, p. 192 (dated circa 1914)

John Updike, Higher Gossip: Essays and Criticism, New York, 2011, p. 317 (titled Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt and dated circa 1914)

Tobias G. Natter, ed., Gustav Klimt, The Complete Paintings, Cologne, 2012, no. 212, pp. 194, 202, 205, 248 and 627; p. 246, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room); pp. 247 and 626, illustrated in color (titled Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer)

Elizabeth Clegg, “War and peace at the Stockholm ‘Austrian Art Exhibition’ of 1917,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. CLIV, October 2012, p. 680, illustrated (in installation photograph of Stockholm, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Österrikiska Konstutställningen, 1917); p. 688 (titled Elisabeth Lederer)

Anne-Marie O’Connor, The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, New York, 2012, pp. 63-64, 157, 198; p. 158, illustrated (titled The Portrait of Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Ken Johnson, “Ethereal and Exalted Spirits of Femininity,” The New York Times, 14 October 2016, p. 17

Exh. Cat., New York, Neue Galerie, Masterworks from the Neue Galerie New York, 2016-17, pp. 231 and 238, illustrated in color (in installation photographs of New York, Neue Galerie, Viennese Silver: Modern Design, 1780 and 1918, 2003-04 and New York, Neue Galerie, Vienna 1900: Style and Identity, 2011)

Tobias G. Natter, ed., Gustav Klimt. Complete Paintings, Vienna, 2017, no. 212, pp. 186 and 571; p. 238, illustrated (in photograph of Serena Lederer’s drawing room); pp. 239 and 570, illustrated in color

Exh. Cat., Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, Gluck: Art and Identity, 2017-18, p. 90 (dated 1914-15)

Uwe Fleckner, Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Christian Huemer, eds., Markt und Macht: Der Kunsthandel im »Dritten Reich«, Boston and Berlin, 2018, pp. 297, 313, 318, note 27 and 319, note 68 (titled Bildnis Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt)

Megan Brandow-Faller, The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy, University Park, 2020, p. 32

Alys X. George, The Naked Truth: Viennese Modernism and the Body, Chicago, 2020, p. 136

Megan Brandow-Faller and Laura Morowitz, eds., Erasures and Eradications in Modern Viennese Art, Architecture and Design, New York and London, 2022, fig. 1.1, p. 67; p. 68, illustrated

Standing at the apex of Gustav Klimt’s career, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer befits the couple who commissioned it—Serena and August Lederer, the artist’s most important patrons. In this magnificent portrait, Klimt brilliantly captured the social prominence and beauty of the sitter, the Lederers’ daughter Elisabeth, through the painting’s lush ornament details, complex palette, dazzling brushwork, and carefully choreographed iconography. Commanding and seductive in scale (measuring six by four feet or 183 by 122 centimeters), Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer was realized when the artist was at the height of his powers and reputation as the premier artist of Austrian modernism.

The painting’s history tells multiple stories. It is the second of three portraits that the artist rendered of three generations of Lederer women, a record of private commissions like none other in his prestigious career. Perhaps more than any other of Klimt’s works, it vividly celebrates the artist’s fascination with and connoisseurship of Chinese art. Confiscated by the Nazi regime during World War II, the canvas narrowly escaped the fate of other works by Klimt in the Lederers’ collection, which were likewise seized but ultimately destroyed in a fire at the war’s end. The portrait has been in Leonard A. Lauder’s collection for forty years, residing less than a mile from the image Klimt rendered many years earlier, Portrait of Serena Lederer (1899), which hangs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (see fig. 1).

One of the final, fully-formulated expressions of Klimt’s oeuvre, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer has Elisabeth frontally placed, standing at center. Her gaze is direct and calm, unlike many of the aloof or dreamy women he captured looking beyond, or without regard for, the viewer. Here, Klimt reveals a fully self-possessed young woman, barely twenty years old. True to the sitter’s features, the face nonetheless bears the artist’s subtle touches, such as the tiny lines at either side of the mouth that turn her otherwise emotionless lips upward in an enigmatic smile. Any expression of self-consciousness is absent, though the rendering of her hands betrays restlessness if not a touch of angst. Venerated by the costumed figures who flank her, she is fantastically attired and wears a regal robe. The work’s symbolism through fashion is paramount to its conceptualization: her clothes project hierarchy and rank, contemporaneity and tradition, individual taste and worldly sophistication. The background’s atmospheric brushwork appears in brushstrokes at once distinct and melding, in ineffable tones of pale blues and greens mottled by passages of peach and rose pink. Every aspect of this painting, from the carpeted floor to the white flower atop her coiffure, from the halo of background figures to the dragon robe adorning her—not to mention the penetrating black of her eyes—was carefully envisioned to seize the viewer’s attention and imagination.

This masterpiece was not realized overnight; Klimt worked on it for years. Whether accurate or not, the story about his inability to let go of the painting involves an exasperated Serena Lederer who, arriving in a car at Klimt’s studio in 1916 (in an early automobile, then a luxury exclusive to the elite), allegedly absconded with the work, fearing that the artist would never part with it otherwise. This portrait would not be the last wherein Klimt depicted a member of the Lederer family; indeed, in 1917, Serena commissioned the artist for a portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, her elegant, elderly mother (and Elisabeth’s grandmother) (see fig. 2).

Klimt first portrayed Serena Lederer when he was just twenty-six years old, including her as one of the many Viennese notables whom he depicted in his city-commissioned view of the old Burgtheater shortly before its relocation in 1888 (see fig. 4). As Tobias G. Natter relates, “Klimt’s painting of the Burgtheater is a key testimony to Viennese society, artistically and sociologically. . . bearers of the highest offices at court, members of the Imperial government, members of the Archduke’s family, actors and actresses, and in the tiers the ‘nouveaux riches.’ Even Serena Lederer, then still bearing her maiden name Pulitzer, is immortalized there” (Exh. Cat. Vienna, Belvedere, Klimt’s Women, 2000-01, p. 62). Serena Lederer, with her lush, black brows and long-lashed, kohl-rimmed eyes, akin to those of her daughter, is shown at upper left in full evening dress complimented by a suitably towering black hat. Most strikingly, she confronts the viewer directly, that is, aware of the artist looking at her and seemingly appraising him.

At this juncture, Klimt was firmly positioned in the Viennese establishment. The artist was primarily employed through official government commissions, including the rococo-infused mythological frescos he painted for the new Burgtheater alongside his brother Ernst Klimt and fellow Austrian artist Franz Matsch. Further commissions followed, notably what would become the infamous 1894 commission of three monumental canvases by the University of Vienna for their Festsaal of the Fakultätsbilder (Faculty Paintings) (see fig. 5).

As with other avant-garde artists across Europe, Klimt and his modernist peers broke with the status quo, namely the Vienna Künstlerhaus, founding the Wiener Secession in 1897. By the time he presented his first of the Fakultätsbilder in 1901, the artist was already growing increasingly controversial. The unsparing nudity of his allegorical figures, an integral part of the murals’ narrative inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of biological evolution, enraged the conservative factions—although a few aligned critics defended him and the Lederers stepped in, Klimt reacted in kind to scathing public criticism. “In 1905, Klimt withdrew the paintings in protest and, with August Lederer’s help, returned his honorarium of thirty thousand kronen. In return, Lederer acquired Philosophy…. To make space for the 13-by-10-foot panel, the Lederers had two rooms knocked into one and invited Josef Hoffmann to redesign the space in 1905” (Sophie Lillie in Exh. Cat., New York, Neue Galerie, Gustav Klimt, The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collection, 2007-08, p. 59).

In the ensuing years, the Lederer family would add the second of the three rejected Faculty murals, Jurisprudence, to their collection, as well as the related oil sketches. And this was not all: landscapes, figure paintings, the famed Schubert at the Piano (which Hermann Bahr called “the most beautiful painting ever painted by an Austrian” (quoted in ibid., p. 60) (see fig. 6), the Beethoven Frieze, Music II and, by all accounts, hundreds of drawings, formed the most important and largest collection of Klimt’s work ever assembled. As one might expect from this level of patronage, Klimt enjoyed a close and privileged relationship with the Lederer family. “The Lederer’s unequivocal endorsement of Klimt’s work led to the artist’s acceptance into their social circle, and at the salons held by Serena—whom Josef Hoffmann called ‘the best-dressed woman in Vienna.’ Klimt was invited to weekly lunches at the Lederer home and was hired as a drawing teacher for both Serena and her young daughter Elisabeth. Klimt was also responsible for introducing Egon Schiele to the Lederers and for arranging his invitation in 1912 to the family home in Györ… where Schiele was to paint the portrait of the Lederer’s oldest son, Erich, then aged fifteen” (ibid., p. 61) (see fig. 3). Serena’s piercingly intelligent gaze, which Klimt had encountered early on in the Burgtheater image, had met its mark.

It is against this backdrop that the intense emotion and intimate grandeur of Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer comes into full focus. Klimt had known Elisabeth since childhood; in the intervening fifteen years since he painted her mother, the artist had moved from his “Whistler-inspired” ethereal portraits of ladies in white, grey, and peach tones (see fig. 7) to his mosaic-like, glittering golden works—Adele Bloch-Bauer I and The Kiss—to the full flowering of his mature portrait style (see fig. 8).

Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer strikes a balance between delicacy and authority. The full-length portrait format has its earliest traces in sculpture from antiquity; in the sixteenth century it was used by monarchs throughout Europe, such as Elizabeth I, to assert dominance and their divine right (see fig. 9). Such compositions also convey wealth in no uncertain terms. The cost of a full-length portrait and the display of fabulous textiles are a statement of political, cultural and economic power. By the nineteenth century this mode of aristocratic portraiture was adopted by government officials and the wealthy bourgeoisie. To be sure, many members of European high society such as those depicted in Klimt’s 1888 painting of the old Burgtheater could—and did—commission full-length conservative effigies in shades of brown and black or vivacious “swagger” portraits, but very few immortalized themselves in daring modernist form.

Klimt’s paintings had always been influenced by what he perceived as the exotic, though informed by first-hand encounters with works in museums, private collections, and curio shops. As Angela Volker writes, “Klimt’s allegories and portraits of his early period look to the art of classical antiquity, by the turn of the century his main inspiration seems to be Japanese and Ancient Egyptian ornament, and, following a journey undertaken in 1903, the magnificent and sumptuous mosaics of Ravenna. From around 1909 until his death, he became increasingly interested in Chinese art. A visit to the Musée Guimet, housing the largest collection of Far Eastern art in Paris, made a lasting impression on him in 1909” (Exh. Cat., Vienna, Belvedere, Klimt’s Women, 2000-01, pp. 44-45). While in Paris, he may well have seen the work of the Fauves; furthermore, Henri Matisse’s work was featured at the Internationale Kunstschau in 1909, which Klimt would have attended. Matisse’s compositions were likely a source of inspiration for Klimt’s increasingly flattened spaces, achieved by merging the floor and wall and embellishing the canvas surface with a profusion of decorative arabesques and floral elements, as seen in Adele Bloch-Bauer II (see figs. 10 and 11). The Fauves’ unleashing of emotive color probably also had a liberating effect, though Klimt’s brilliant pastel hues, punctuated by bold greens and oranges as well as fluid, individuated brushstroke, were his alone.

As Emily Braun has demonstrated in her focused study on the present painting and its iconography, “the Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer is one of several full-length images of society women dating from 1912-18…. They announce two new developments for Klimt in the genre of commissioned portraiture…. The first of these is his ‘carpet paradigm,’ wherein the floor design adds a whole other register of exuberant and directional patterning that flattens the space, while simultaneously creating depth of field… Beginning in 1912, the artist decorates a distinct floor area perpendicular to the wall that allows the viewer greater access into the picture…. The second novelty is the appearance of East Asian motifs and their profusion in carpets, backplanes, and dress…” (Exh. Cat. New York, Neue Galerie, Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900-1918, 2016-17, p. 58). Here, Elisabeth Lederer is presented on a carpet dominated by orange and pink hues, with elements reminiscent of both Josef Hoffmann’s designs for the Wiener Werkstätte (the black and white borders) and ancient Chinese jades (the irregular green and white circles) (see fig. 12).

The most telling motif in this regard is the ornate Chinese Dragon Robe that forms her gossamer train, a garment that symbolizes political and social power; indeed, such an ornate robe was only worn by the Emperor and specific members of the Court, denoting imperial presence. Klimt wove these historical references and ornamental fantasies into his pictorial tapestry.

Closer examination of the Dragon Robe, other bespoke motifs, and the painting’s compositional design lends specificity to the influence of Chinese art on Klimt’s work; the shapes of the dragons indicate that this was likely based on a robe from the late Qing dynasty during the Guangxu period (see fig. 13). Beyond the dragons, the composition is laden with symbols, all signifying specific meaning. For example, as Braun explains, “The numerous little ‘mushroom caps’ represent the curly profiles of clouds in the stylized form of the lingzhi fungus, an auspicious symbol for longevity. Pink and white bats stand for good luck, as they fly amidst blossoms and stars” (ibid., p. 72). These ornate robes are also visible in painted portraits (see fig. 14). The figure—whether Emperor or, as in the case of the painting illustrated here, Consort Chunhui—is always posed frontally, seated on an elaborate throne placed on a patterned carpet. When compared to the present work, the structural similarities are striking.

Chinese and Japanese artworks were not just curiosities for the artist. He “was deeply familiar with Chinese and Japanese art and artifacts,” writes Braun, “and his own collection was stored and exhibited in the front room of his studio in black cabinets designed by Hoffmann (see fig. 15). The artist’s holdings included Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, kimonos, netsuke, and lacquered pieces, as well as Chinese samurai and Qing court robes, porcelain, theater puppets, and other decorative objects” (ibid., p. 70). A picture of his companion Emilie Flöge dressed in a dragon robe, taken in 1913 during a summer trip to the Attersee, further attests to Klimt’s fascination with and appreciation for East Asian art (see fig. 16). Such awareness is embodied in the worldliness of the Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer.

It is likely that some of the characters who frame and greet Elisabeth Lederer were based on prints and objects from Klimt’s own collection. These actors in a supporting role include the two women at center left and the bright-orange-cloaked male figure at center right. The female figures turn their faces to the subject of our gaze, Elisabeth Lederer, holding a lantern between them that illuminates a path toward her. With his sword sheathed and arms slightly raised, the man at right pays her deference. At upper left, two scholar figures with shaven heads clutch fans. Other tiny, if mighty, attendants include military types bearing standards and another astride a white horse. Each character is distinct and separate from the others, unlike the more bohemian Bildnis Friederike Maria Beer (1914) where the overlapping figures form a chaotic screen (see fig. 17), seemingly more focused on their internal battle scene than on the figure posed before them. In Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer, “the courtiers attend to her and we pay attention as she receives our gaze in a coordinated act of looking” (ibid., p. 71). Infra-red reflectography conducted on the painting reveals that Klimt had planned two other figures on either side of Elisabeth much lower down, just above the carpet; he likely removed these anchoring touches because they would have compromised the floating, otherwise otherworldly atmosphere of the backdrop.

Despite the imperial allusions, Elisabeth Lederer is clearly a contemporary woman dressed in the most current continental fashion—a Poiret or Poiret-inspired hobble skirt evening ensemble complete with an elegant floral wrap encircling her bodice. The flower or butterfly that sits just above the sitter’s head evokes the delicacy of the floating butterflies and white flowers in Harmony in Grey and Green by James McNeill Whistler (see fig. 18). Whistler, the pioneer of modernist portraiture, notably excelled in his treatment of flattened space and free-floating ornamental details to create an enveloping mood, an aesthetic strategy which Klimt took even further.

Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer was painted during World War I—the so-called “Great War”—for its unprecedented loss of life, untold destruction, and destabilization of the balance of power in Europe. It is all the more impressive, then, that shortly after its completion, the portrait travelled through Europe during the height of the conflict in 1917 to be exhibited in the Österrikiska Konstutställningen at the Liljevalchs Konsthall in Stockholm. Klimt died a year later, just as the Empire collapsed. In her memoirs, Elisabeth Lederer, who was very close to the artist and called him “Uncle,” remembers his death as the first great emotional blow in her life. In 1921 she converted to Protestantism and married Wolfgang Bachofen von Echt, the heir to a beer-brewery dynasty. She became the Baroness Bachofen von Echt—indeed, much of the historic literature on the present work bears this title. She and her husband had only one child, a son who died young shortly after the Anschluss in 1938; that same year, her husband divorced her. Under the Nazi regime, Elisabeth’s situation as a single, Jewish woman was precarious. In 1939 she penned a memoir about her young life, especially her closeness to Klimt. She submitted this as part of a petition to have Gustav Klimt, not August Lederer, recognized as her biological father—a life-saving fiction with which her mother complied. Serena, who herself would flee to Budapest that year, signed a document acknowledging Klimt’s paternity. After various types of examinations, Elisabeth was recognized as the artist’s illegitimate daughter and therefore as possessing some of his “Aryan” blood. She died in Vienna in 1944 and was buried next to her son at Hietzing Cemetery, where Klimt was also interred.

Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer had always hung in the Vienna home of August and Serena Lederer (they also had a country estate in Serena’s native Hungary). Their art collection was among the most distinguished in Vienna, including prized renaissance paintings and bronzes by Simone Martini, Lucas Cranach, and Benvenuto Cellini—not to mention over eleven paintings by Klimt and hundreds of his drawings. In 1938, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer was impounded by the Nazi government and transferred in 1939 to a storage facility, where it remained for the duration of the war alongside Klimt’s portrait of Serena Lederer and Schiele’s portrait of Erich Lederer, as well as furniture and decorative objects that had also been looted. Referred to as the family pictures (Familienbilder), these paintings were not included in the 1943 Klimt retrospective at the Belvedere, which featured eleven others from the Lederer’s incomparable trove. Subsequently and to protect this cache from harm, the eleven paintings (but not the portraits) along with other works from the museum were transferred to the Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria. At the end of the war as the Nazis fled, the building and all the artworks inside went up in flames. In 1948 the three family portraits were returned to Erich Lederer, who had fled to Switzerland during the war. It is a great—and poignant—irony that these paintings, which depicted members of a Jewish family, survived the war because of their segregation from the rest of the Lederer’s collection.

One of the most enduring fascinations with the culture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire is the beauty of the works that encapsulated its breathtaking creativity and that also survived. Yet as much as Klimt’s Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer embodies a specific moment in time, it also transcends it. Painted on the cusp between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it is a masterpiece of portraiture, one whose pictorial inventiveness, daring and decorative effusion, propelled the course of modernism.