Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio

“Art dies but is saved by gesture.”

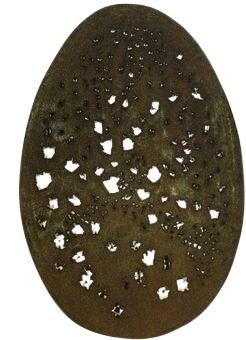

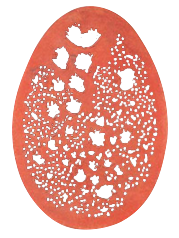

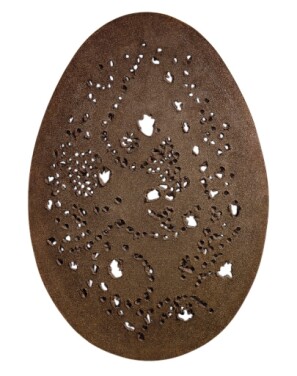

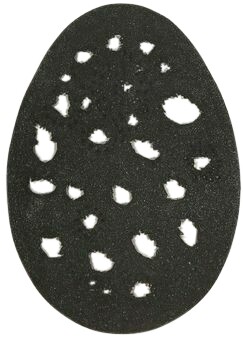

Through lacerated cavities, impassioned apertures, and the ghost of the artist’s own hand clawing at the canvas, Lucio Fontana plumbs the absolute limits of painting as he assails the burnished bronze of Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio’s lustrous surface, thus asserting his most powerful contribution to twentieth century art: the rupture of the picture plane. Executed in 1963, the present work ranks among the most significant of La fine di Dio, or “The End of God”, paintings, which represents the utter apex of his artistic enterprise. Of the thirty-eight works in the series, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio is the third to be recorded in the artist’s catalogue raisonné and is one of just ten rarified examples executed with glitter, others of which reside in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid and Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan. Moored by its conceptual rigor and treasured in just two other private collections in its lifetime before being acquired by visionary dealer and advisor Daniella Luxembourg, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio exudes a bombastic yet sepulchral majesty as it preaches the death of painting as we know it. If it were the masters of the High Renaissance who constructed linear perspective, the Impressionists who distilled the image into rippling color and light, the Cubists who shattered form and space, and the Abstract Expressionists who eschewed representation altogether, then it is Fontana’s La fine di Dio paintings that constitute the total massacre of the surface to which Western art has been beholden for centuries.

"Now in space there is no longer any measurement. Now you see infinity in the Milky Way, now there are billions and billions… And my art too is all based on this purity of the philosophy of nothing, which is not a destructive nothing but a creative nothing… And the slash, and the holes, the first holes, were not the destruction of the painting… it was a dimension beyond the painting, the freedom to conceive art through any means, through any form."

Here, Fontana takes the very basis long regarded as an illusionistic portal or didactic vessel and, in a spectacular display of ingenuity and irreverence, literally pierces the perennially exalted picture plane. The so-called window represented within the confines of his stretcher bars has been impaled, and what it contains, Fontana reveals, is only an immeasurable void. “With one bold stroke,” art historian Erika Billeter observed, “he pierces the canvas and tears it to shreds. Through this action he declares before the entire world that the canvas is no longer a pictorial vehicle and asserts that easel painting, a constant in art heretofore, is called into question. Implied in this gesture is both the termination of a five-hundred year evolution in Western painting and a new beginning, for destruction carries innovation in its wake.” (Erika Billeter quoted in: Exh. Cat., New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, 2006-07, p. 21) Digging his own fingers into pastose layers of rose gold glitter and pinko oil, Fontana draws upon codified aesthetic and theoretical lineages only to cast them to history, instead engendering in La fine di Dio an ever-palpable present in which his catalytic impressions of severity and radicality remain immortalized.

The spellbinding twilight effects of Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio’s umber luster further underscore how formative the scientific developments in space exploration of Fontana’s lifetime were on his output, from J. Robert Oppenheimer’s 1939 theory on black holes to the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to Yuri Gagarin’s odyssey into space. Fontana labored for more than a decade on his Spatialist theories, producing tagli and buchi before arriving at La fine di Dio, which allowed him to advance artmaking into a dimension far more radical than the previous aims of Modernist abstraction, thus expanding the idea of space itself—space as volume, the cosmos, a creative gesture, and artistic theory. The result is aptly one which brings to life Georges Lemaître’s description of the Big Bang: “the Cosmic Egg exploding at the moment of creation.” Expanding upon Fontana’s obsession with space, Anthony White writes: “This radical emptying out in favor of space culminated in the End of God, a series of canvases shaped in the form of an oval. Painted in highly synthetic colors, torn open with holes, and labeled ‘astral eggs’ for exhibition at Galerie Iris Clert, Paris, in 1964, these works evoke a vastly expanded, infinite conception of the cosmos. Speaking about the far reaches of space into which vehicles such as the Russian satellite Sputnik I penetrated, in 1957-58, Fontana argued that ‘here is the void, man is reduced to nothing.’ If the breathtaking discoveries of space travel had inspired the German Zero artists to celebrate the idea of ‘shooting the viewer into space,’ for Fontana they became the basis for a zen-like prophecy of a posthuman future.” (Anthony White, “Not an Against but a For: Fontana and European Art, 1947-1968,” quoted in: Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, January - April 2019, pp. 58-59)

Lucio Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, La Fine di Dio Paintings with Glitter, 1963-64

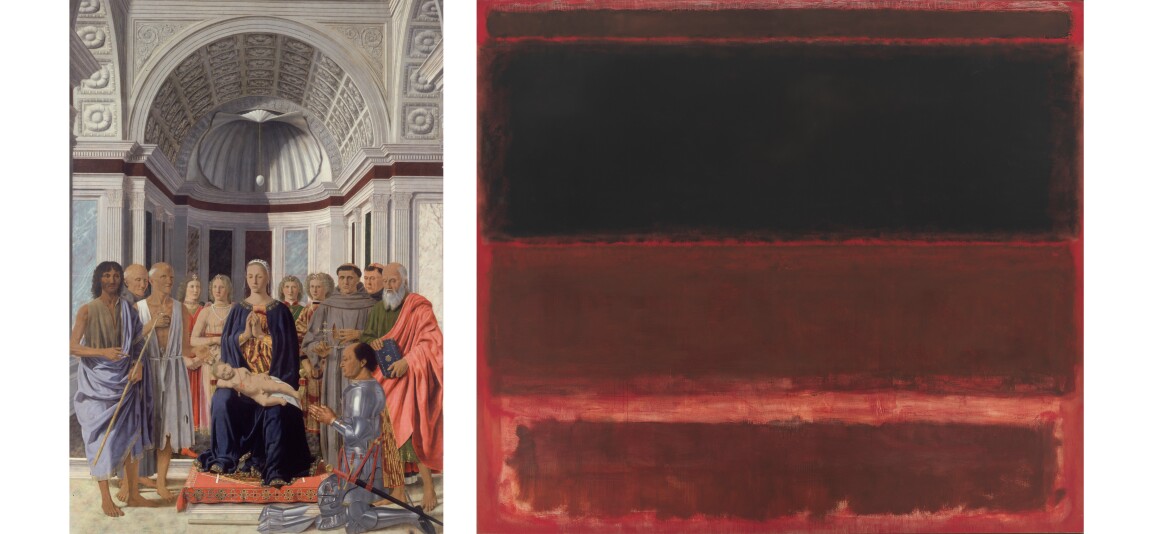

La Fine di Dio series was executed alongside three critical exhibitions in Zurich, Milan, and Paris. Though shown at Galleria dell'Arte, Milan in 1963 as Le Ova—or “the eggs”—and Galerie Iris Clert, Paris as Les Oeufs célestes—or "the celestial eggs"—Fontana subsequently changed their collective title to La fine di Dio. Their ovoid form culls from vast and potent historical associations with fertility and regeneration, spanning Egyptian hieroglyphs, Hieronymus Bosch, Piero della Francesca, and Constantin Brancusi. Thus, the myriad semiotic interpretations of the image are invoked, made into a site of catastrophe as Fontana eviscerates its image. Its punctures betray the process of its manufacture, divorcing the painter from his brush and earth from existence. “Man must free himself completely from the earth,” Fontana explained, “only then will the direction that he will take in the future become clear. I believe in man’s intelligence—it is the only thing in which I believe, more so than in God, for me God is man’s intelligence—I am convinced that the man of the future will have a completely new world.” (Lucio Fontana in June 1968, quoted in: Exh. Cat., London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Lucio Fontana, 1988, p. 36)

“Man must free himself completely from the earth,” Fontana explained, “only then will the direction that he will take in the future become clear. I believe in man’s intelligence—it is the only thing in which I believe, more so than in God, for me God is man’s intelligence—I am convinced that the man of the future will have a completely new world.”

If the governing law of physics states that energy can be neither created nor destroyed, Fontana achieves a conceptual coup that defies the constitution of space itself, mourning the end of painting while heralding the birth of an artform altogether new – collapsing a conceptual death and birth into one canvas. Its constellations, which erupt across glints of pewter glitter and cast shadows through its openings, and like Yves Klein’s leap into the void or Alberto Burri’s flaming plastic, Fontana here finds himself at the very threshold of creation. “Art dies,” he wrote in 1948, “but is saved by gesture.” (the artist quoted in: Exh. Cat., New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Lucio Fontana 1899-1968: A Retrospective, 1977, p. 19) With every blow to the surface in Concetto Spaziale, La fine di Dio, Fontana proves this to be true—an utter triumph of invention which redirected, indelibly, the course of art history.