“A blot is not an abstraction, really, because we know what it is. It’s a blot. And a blot is a particular kind of figure. I wanted to disrupt expectations immediately. I thought that was a dramatic way of introducing looking and seeing.”

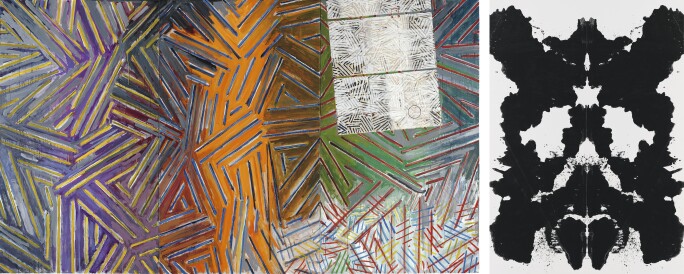

Exploding with chromatic vibrance, Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Blot) from 2015 powerfully embodies the artist’s continued negotiation of the Western art historical canon through a nuanced investigation of the tenets of race and representation. Within Marshall’s figurative oeuvre, the Blot series uniquely locates his work in the context of what Clement Greenberg described as ‘American-Type’ painting. Within the mesmerizing abstraction of the present work, Marshall invokes the legacy of the Abstract Expressionist and Color-Field painters while simultaneously summoning the Pop legacy of Andy Warhol’s iconic Rorschach paintings – a series of Twentieth Century art movements which celebrated conspicuously few Black artists. By exploring abstraction, Marshall interrogates the gendered and racialized practices of art history, reinserting Black art into a movement it was obscured from. Marshall explains, “A blot is not an abstraction, really, because we know what it is. It’s a blot. And a blot is a particular kind of figure. I wanted to disrupt expectations immediately. I thought that was a dramatic way of introducing looking and seeing.” (Kerry James Marshall in conversation with Sarah Douglas, ArtNews, 2 March 2016) Underscoring the significance of the present work, Marshall notably selected the present work to be shown at the 2015 Venice Biennale, when the artist was exhibited as part of the group show All the World’s Futures at the Central Pavilion, alongside another (Untitled) Blot from 2015, which is today held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“For people of color, securing a place in the modern story of art is fraught with confusion and contradictions about what and who they should be—black artists, or artists who happen to be black. A modernist has always looked like a white man, in one way or another. Universality has, unquestionably, been his gift to bestow on others.”

Born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, from 1963, just a couple years before the eruption of the Watts Riot, Marshall’s upbringing greatly influenced his desire to readdress, reinsert and re-envisage black representation within artistic discourse. Amongst his potent yet nuanced embodiments, in Untitled (Blot), Marshall’s striking color palette of red, black and green is charged with symbolic potency. With its origins in the Universal Negro Improvement Association (U.N.I.A.) founded in the 1920s by the Jamaican-born black nationalist Marcus Garvey, this tricolor forms the tripartite chromatic register of the Pan-African flag. Symbolizing the blood, skin and land of the African people, the flag would become an emblem of the Black Power Movement, specifically the more radical Black Panther Party, in its address to the African diaspora for which it proposed a radical new solidarity between all peoples of African descent. Recalling David Hammons’s influential series of African American Flags (1990), Marshall’s integration of the tricolor in Untitled (Blot), situates this work within a wider history of social justice and activism.

Right: ANDY WARHOL, RORSCHACH, 1984. MUSEUM BRANDHORST, MUNICH. ART © 2020 ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

The present monumental abstraction is reminiscent of the Rorschach psychological tests, designed to understand one’s underlying emotions and personality. Through the mirroring of intricate layers of luscious jet-black, greens, and red intensified by its reflection across the canvas, Marshall encourages the viewer to use the blot as a self-diagnostic tool. Rife with symbolism, Marshall’s Blot series subverts the hegemonic concept of perception, illuminating the prejudice and assumptions inherent to race relations in America. Through the iconography of mirrors and optical deception, Marshall illustrates the realities of privilege, a concept that may seem obscure to the self and require a counter-presence to reflect reality, and reimagines the ink-blot tests to question the underlying lens through which Black and white Americans perceive each other and themselves. Exemplifying the intent which defines the very heart of his practice, Untitled (Blot) amalgamates Marshall’s aesthetic and intellectual pursuit to insert postcolonial narrative into the history of art.