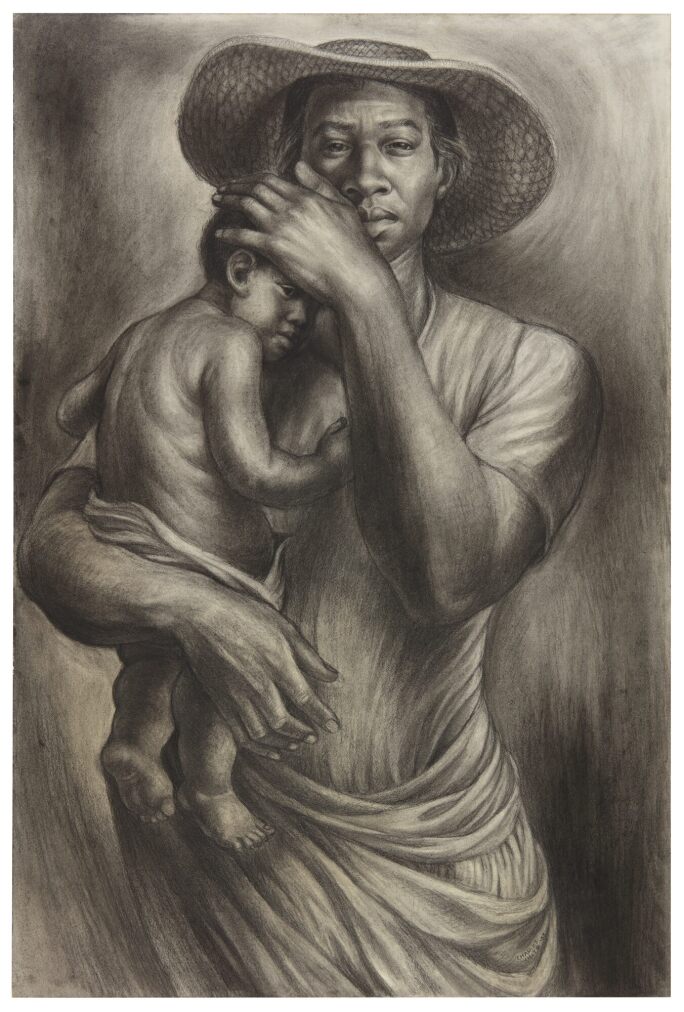

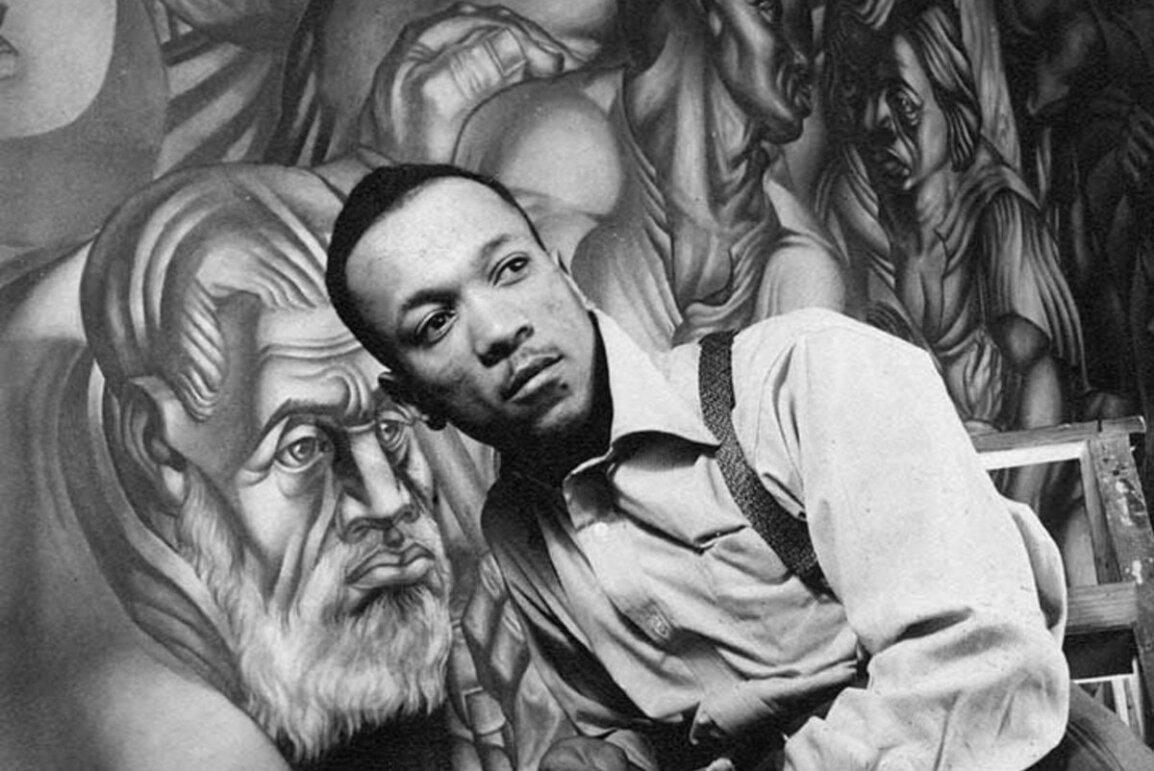

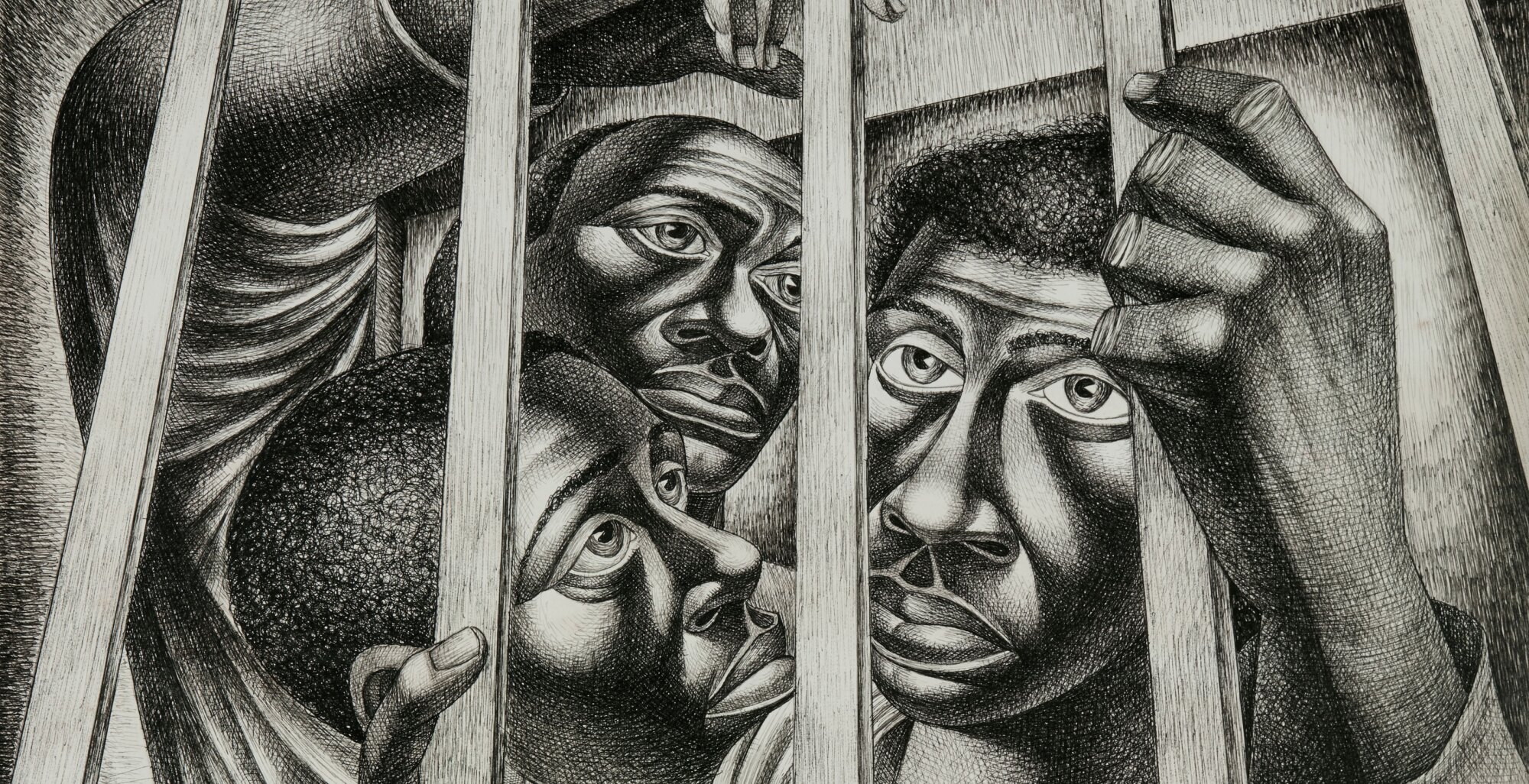

Majestic yet harrowing, poetic yet potent, The Ingram Case from 1949 is a stirring testament to the emotive power and immediate graphic force of Charles White’s celebrated oeuvre. Rendered in ballpoint ink, this work testifies to White’s unprecedented aptitude as a draftsman: composed of innumerable minute motions, White sculpts his figures in ink as if shaping them from clay, resulting in an image so multi-dimensional that it almost defies the limitations of the sheet. Created at a time when Abstract Expressionism had begun to take hold in America, The Ingram Case epitomizes White’s groundbreaking use of figuration to create conversation around the social issues of his day. Testament to White's significance within the narrative of Twentieth Century American Art, the artist was recently the subject of a major retrospective exhibition, organized by and traveling to the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2018-2019. In the present work, White gives vision to the story of Rosa Lee Ingram and her two sons – a family who, in the 1940s, became the subject of the most explosive capital punishment cases in American history. As potent representation of this key moment in the Black American history, the present work powerfully exemplifies the socially committed and activist-inspired nature of White’s practice, while simultaneously testifying to his staggering technical skill. As eloquently summarized by Harry Belafonte, famed musician and friend of the artist: “There is a powerful, sometimes violent beauty in his artistic interpretation of [Black] Americana.” (Harry Belafonte in: Harry Belafonte, James Porter and Benjamin Horowitz, Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White, Los Angeles 1967, p. 1)

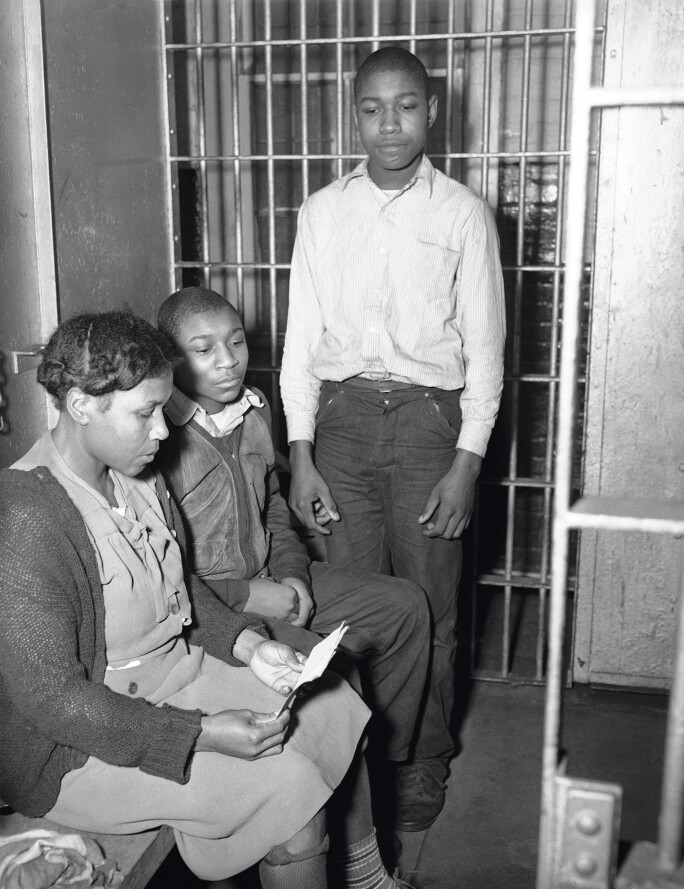

“Notice in his pictures the use he has made of hands – not hands as an anatomical detail, not hands which are abstract forms for design, but hands which proudly demonstrate the glory of man as man… hand[s] pregnant with resistance and strength – even as the hands of Mrs. Ingram and her two sons overwhelm the iron bars which they clutch”

PRIVATE COLLECTION. SOLD AT SOTHEBY'S NEW YORK IN 2019 FOR $1,760,000

Art © 2021 The Charles White Archives

Within White’s celebrated output, The Ingram Case is a particularly poignant embodiment of the artist’s championing of civil rights causes. In the present work, White presents the figures of Rosa Lee Ingram and her two sons – figures who would become icons for the civil rights and social justice movement. In 1947, Ingram, a widowed mother of fourteen, and two of her sons were accused of killing their neighbor, a white sharecropper, after enduring years of his harassment and abuse; although all three were initially sentenced to death, the public outcry was so immediate and vigorous that the three sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. The continued protest against the incarceration of the Ingram family became a central catalyst for civil rights activists – and in particular, women – across the political spectrum and served as a rallying cry and key cause for such groups as the Women’s Committee for Equal Justice and the Sojourners for Truth and Justice. The public outcry continued and intensified until, in August 1959, the Georgia Supreme Court was forced to cede to the consistent protests and granted Rosa Lee Ingram and her two sons parole.

The present work is one of two seminal drawings in which White explores the subject of the Ingrams: the other, Ye Shall Inherit the Earth from 1953, was used as illustration on a Mother’s Day Card sent to Ingram in prison in 1954, assuring her of the continued efforts being made on her behalf. Despite the specificity of White’s narrative however, there is an undeniable universality to the poetic beauty of the three figures within The Ingram Case. As described by Belfaonte, in the early monograph Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White: “When in the presence of Mr. White’s work, his people take on a reality all their own. You feel that somewhere, sometime, some place you have known these people before… You are enriched by the experience of having known Charles White’s people, who are like characters from a great novel that remain with you long after the pages of the book have been closed.” (Ibid., p. 1)

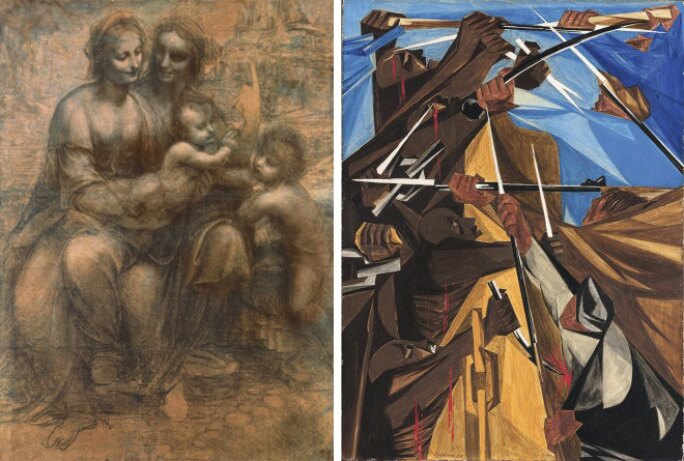

Right: JACOB LAWRENCE, FROM THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE: PANEL NO. 5, 1954 AND 1956. IMAGE © THE JACOB AND GWENDOLYN LAWRENCE FOUNDATION / ART RESOURCE, NY. Art © 2021 Jacob Lawrence / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As she meets the viewer’s gaze, the foremost figure of White’s drawing exudes a palpable strength, one fist reaching towards us and the other clenched with totemic solemnity upon the bars of her cell. Behind her, the figures of Ingram’s two sons look and reach, not towards us, but towards their mother, as if to draw strength or resolve from her quiet dignity. By shaping the silhouettes and shadows of his forms through minute lines and delicate crosshatches in ink, White’s figures present with a statuesque intensity: the drawing is at once sharp yet supple, bold yet nuanced. White’s unprecedented skill as a draftsman is perhaps most evident in the faces – and particularly, in the gazes – —of his figures, where deep contours and subtle gradients draw a staggering emotive depth from the monochromatic visages. Speaking in terms particularly reminiscent of the present work, Belafonte describes: “His strokes are bold, courageous and affirmative. His lines are clear, his people are alive… the story of living manifest in their faces and their bodies.” (Ibid., p. 1) In a moment where many artists abandoned figuration for the schools of abstraction and nonobjectivity, White continued to strive for more potent expressions of humanity and to explore greater depths of truth through representation. Nowhere is this more evident than in The Ingram Case, where figuration achieves an honesty and poignancy perhaps impossible in pure abstraction.

Exemplified within The Ingram Case, White’s distinctive approach to portraiture communicates universal human themes while simultaneously exploring intensely personalized narratives, ultimately creating a body of work that continues to resonate deeply today. His contribution to the course of Twentieth Century art history cannot be understated, not only as a supremely talented artist and social historian, but also as a mentor and teacher to some of today’s best-known artists. In the preface of the exhibition catalogue for Charles White: A Retrospective, former student Kerry James Marshall writes of his beloved teacher at the Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles County: “The labor, the work, in Charlie’s drawings is palpable. One can follow the process through his technique and understand exactly how the image came to be on the page or the canvas. His most accomplished drawings achieve true perfection. The effect is dazzling, efficient, and never extravagant. An atmosphere of stillness and quietude envelops the space in and around the work. I can’t help remembering a Shaker motto I read somewhere that governs their sense of piety and discipline: ‘Hands to work, hearts to God.’ The terms art and work gain embodied meaning in the best of his pictures.” (Kerry James Marshall, “A Black Artist Named White,” in: Exh. Cat., Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago (and traveling), Charles White: A Retrospective, 2018, p. 19) Indeed, White’s commitment to creating powerful images of Black Americans—and the distinctive figurative style in which he did so – has served as key influence not only for Marshall’s work, but for that of Kehinde Wiley, Jordan Casteel, and numerous celebrated others who render Black figures with searing specificity. Marshall concludes: “Under Charles White’s influence I always knew that I wanted to make work that was about something: history, culture, politics, social issues. … It was just a matter of mastering the skills to actually do it.” (Ibid.)