D8575

-

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story -

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's -

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

“It might be that Lichtenstein only appears to conform to this old model of sculpture, in part to complicate it, even to refashion it for his own ends... Yet in Lichtenstein there is no stable, a priori ground—it is often, quite literally, a void, an empty space—and meaning accrues through the image alone.’”

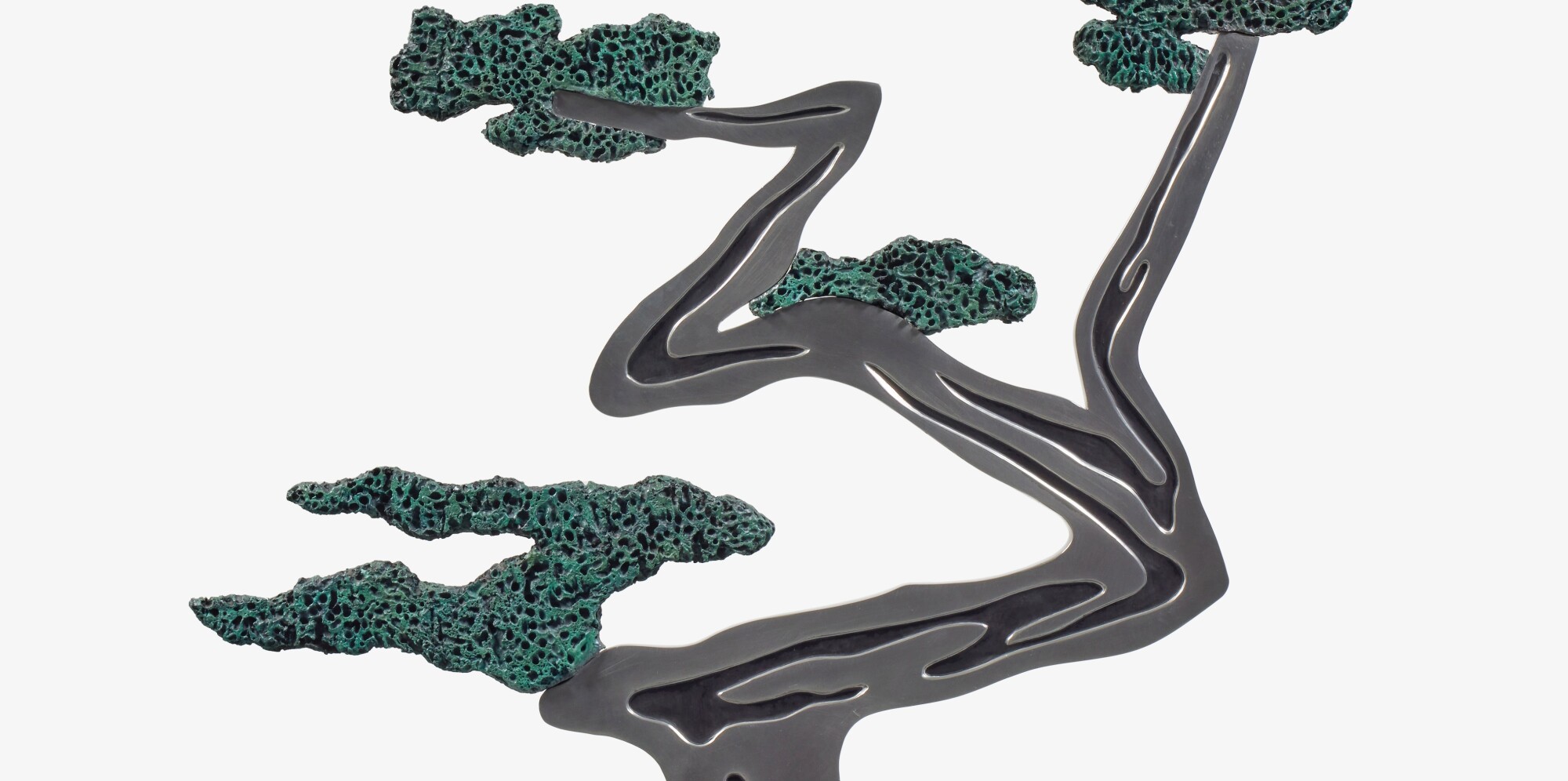

Serene and refined, Bonsai Tree elegantly evokes the iconic Japanese practice of cultivating serpentine trees in striking forms, embodying Roy Lichtenstein’s career-long synthesis of cross-cultural influences through his distinctive Pop sensibility. The history and masterful artistry of Bonsai in Japan and the similar Chinese tradition of Penjing, which originated approximately 1300 years ago, represent a form of rarefied, controlled beauty through sustained patience and care. Through economy of line and striking three-dimensional composition, Lichtenstein echoes the graceful contours of the Japanese artform in Bonsai Tree. Simultaneously majestic and subtle, expressive and tranquil, Lichtenstein here uses his signature Pop technique and irreverent inquiry both to pay homage to a cultural tradition and to illuminate the frequent generalization of Eastern motifs by Western artists for centuries. In the 1990s, Lichtenstein embarked on his final two major series, Landscapes in the Chinese Style and his Interiors, through both of which he would continue his career-long investigation and reinterpretation of art history and contemporary culture through his distinctive Pop vernacular. Situated between these two series, Bonsai Tree is an exemplar of Lichtenstein’s mature practice and exploration of three-dimensional expression, embodying the radical inquiry and masterful invention of his oeuvre.

In the 1960s, Lichtenstein began his probe of the art historical canon, contending with a range of influences from Pablo Picasso’s Cubism to Piet Mondrian’s abstracted picture planes and the architectural monuments of ancient Egypt and Greece. Lichtenstein reinterpreted and reevaluated these visual icons through the representational systems of contemporary mass media. Applying the visual strategies of comic books and advertisements, Lichtenstein developed his compositions using Ben-Day Dots, bold contour lines, and flat planes of color. In each case, Lichtenstein played with a representational cliche of an artist or cultural iconography, responding to the commodification and proliferation of art as a symbol in the image-saturated culture of the Post-War era.

In 1991, Lichtenstein turned his focus to East Asian art, developing a series of paintings, collages, works on paper and sculptures inspired by the visual tropes of East Asian art in the Western imagination. Lichtenstein’s interest in Chinese art though began almost five decades prior. Stationed in London during World War II, twenty-one-year-old Lichtenstein wrote home to his parents: “I bought a book on Chinese painting, which I could have gotten in New York half the price. I’ll probably send it home with my collection of African masks, as my duffle bag now weighs more than I do, with all the art supplies.” (the artist cited in: Exh. Cat., Hong Kong, Gagosian Gallery, Roy Lichtenstein: Landscapes in the Chinese Style, 2011, p. 7) Later, when Lichtenstein returned to Ohio State University to complete his undergraduate and graduate degrees after the war, he enrolled in classes on East Asian art history. Lichtenstein recalled: “The thing that interested me was the mountains in front of mountains in front of mountains, and huge nature with little people… We all have a vague idea of what Chinese landscape look like—that sense of grandeur the Chinese felt about nature.” (the artist quoted in: Calvin Tomkins, “The Good China,” The New Yorker, 30 September 30 1996 (online))

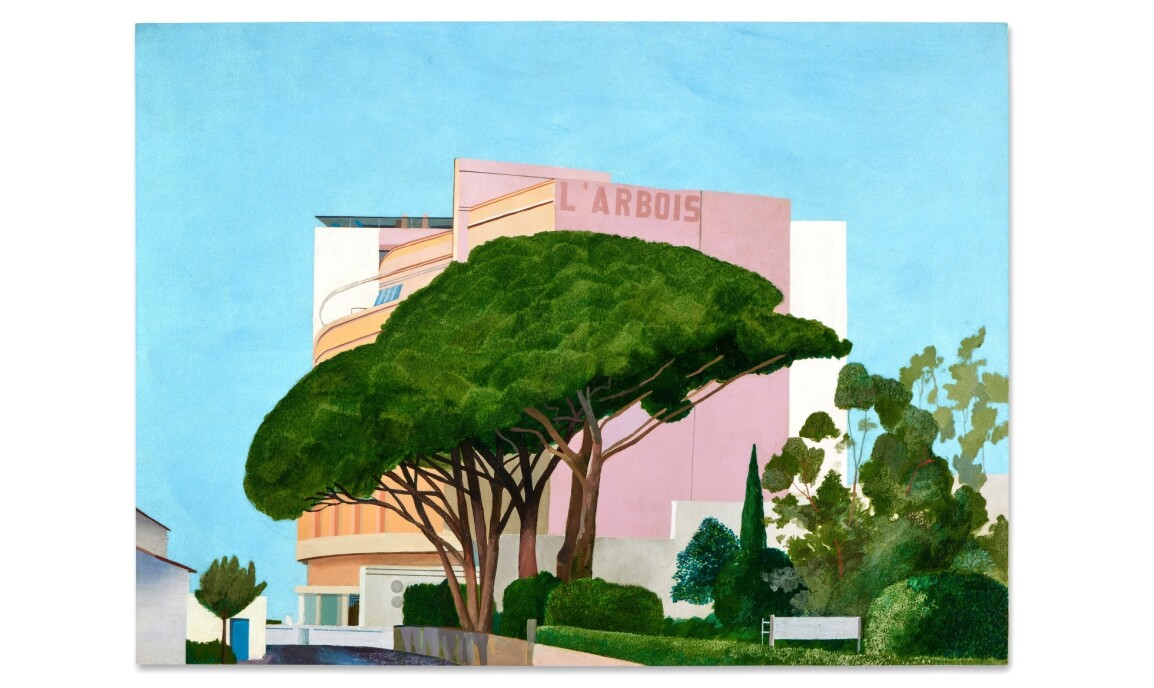

Lichtenstein’s pursuit of East Asian visual tropes through his Landscapes in the Chinese Style series developed in parallel with his iconic Interiors series. Inspired by the domestic interiors illustrated in the Yellow Pages, Lichtenstein’s Interiors featured living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens, which frequently included miniature versions of his own artworks or those from art history. Both series would occupy the artist in his final decade, representing the artist’s continued quest for reinvention and reflection in his mature practice. The present work sits at the nexus of these two seminal series. The image of the Bonsai tree first appears in Lichtenstein’s oeuvre in 1991 in his painting, Interior with Bonsai Tree. Throughout the series, Lichtenstein sought to insert instantly recognizable art historical and cultural symbols in his compositions, creating layered dimensionality and reflecting upon both the canon and his own practice.

"The thing that interested me was the mountains in front of mountains in front of mountains… And the huge nature with little people. We all have a vague idea of what Chinese landscapes look like--that sense of grandeur the Chinese felt about nature. In my paintings, it's not nature, of course, it's just dots. But it wasn't nature when they did it, either. Any painting is so far from the real look. It's a symbol that reminds you of reality, sometimes, if it does."

Lichtenstein’s quotations from visual culture are inherent reproductions—reductive representations which stimulate the viewer’s recognition through sparse means. Through refined lines and a voided space, Lichtenstein evokes the presence of the potted Bonsai tree and profoundly disrupts the basis of the sculptural form. Lichtenstein’s Bonsai Tree retains the planar, comic-book-like two-dimensionality of his paintings and drawings but exists as a three-dimensional form. The sponge-like application of pigment in his painting Interior with Bonsai takes on a three-dimensional presence in the present work. The artist blurs the boundaries of the sculptural medium, challenging its very substance and definition. He renders space and volume through absence; in transposing his visual systems and cues, such as bold contours used to convey depth and volume. Bonsai Tree is a superlative example of Lichtenstein’s acclaimed mature sculptural practice, embodying the central artistic explorations of his final decade.