Executed in vibrant shades of red, blue and black, David Hockney’s Ian Watching Television is the artist's quintessential Cubist portrait, and embodies a pivotal moment in his oeuvre. It was during this time that Hockney – already an internationally celebrated artist—truly mastered his Cubist exploration of portraiture and space, a style he had begun interrogating in earnest in 1980. Having long been fascinated by the Spanish master, the 1980 Pablo Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York reinvigorated Hockney’s belief that Cubism marked a critical turning point in pictorial representation. Ian Falconer, subject of the present work and both a collaborator and former boyfriend of Hockney’s, who would go on to provide creative direction for opera and theatre productions around the world and create the highly successful Olivia children’s book series, served as a muse and frequent model throughout this explorative period. Each drawing and painting of Falconer brought Hockney closer to the all-encompassing, dynamic, physical effect he sought to bring to his Cubist-style portraits. More than any other portrait he produced in the 1980s, Ian Watching Television achieves Hockney’s radical desire to obliterate the space between viewer and painting through his use of multiple perspectives. Testament to its quality, the painting was included in Hockney’s travelling retrospective in 1988-89, which travelled from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York before ending at the Tate Gallery in London, and entered the prestigious collection of Morris and Rita Pynoos in 1988.

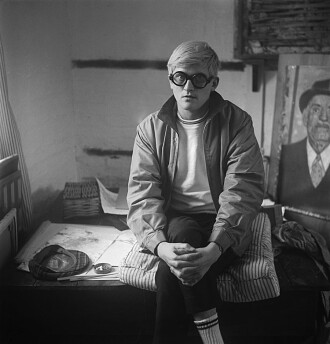

Falconer and Hockney were introduced by Henry Geldzahler at a party in 1979 or ‘80 and immediately formed a strong bond. Falconer had just begun his classes at Parsons and was quickly drawn under Hockney’s creative wing; shortly after, the young artist moved to Los Angeles and attended the Otis Art Institute while working in Hockney’s studio. “David taught me how to draw but, more importantly, he taught me how to look at paintings,” Falconer recalled, “He taught me how to see.” (Ian Falconer quoted in: “The David Hockney Compedium”, Sessums Magazine, 12 September 2017 (online)) Although the two men’s romantic relationship was brief, ending by August 1983, they developed a lasting friendship, and Hockney invested trust and confidence in this young talent, inviting Falconer to work with him on many of his stage design projects during the ‘80s and ‘90s. From 1986 to 1987, the year in which Ian Watching Television was painted, Falconer assisted Hockney with the costume designs for the Los Angeles Opera’s production of Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. The project consumed Hockney: he produced no paintings during the latter half of 1986 and created only a few paintings of the opera’s characters and staging in 1987 for his own use while planning the design. Hockney was already exploring Cubist ideas of multiple perspectives in three dimensions in his stage designs and was excited by the potential implications they could have on his two-dimensional work.

It was during this time that Hockney revisited his earlier portraits of Falconer. Hockney had begun investigating Cubist viewpoints in earnest in 1982, when he began joining Polaroids together to create a composite image of multiple views in the fashion of Cubist still-lifes. Falconer was featured in some of the earliest of these works, which Hockney continues to explore today, such as Ian with Self-Portrait (2 March 1982) and Ian and Me Watching a Fred Astaire Movie on Television (6 March 1982). That summer, he began a large painting that showed the immediate effects of his Polaroid experiments, entitled Four Friends or later David, Celia, Stephen and Ian, August 1982. This work consists of 8 panels depicting the 4 sitters, each with multiple facial features or extra limbs. Falconer is featured in the far-right panel with a black background and a burnt orange floor, in stark contrast to the bright blues and yellows in the other portraits. He has blonde hair, blue eyelashes, a third arm and leg, and a second chin. There is a sense of movement in his body: far from being static, we feel that Falconer is moving on the canvas, or that we ourselves are walking by him quickly. His arms feel unfinished, as though he is still in motion, an impression underscored by the blurring of his shoe. Another indelible influence on Hockney was the work of Henri Matisse and his rendering of space and the human form. The present work specifically calls to mind Matisse's 1906 Young Sailor II with the angularity of the subjects face and postural contortion.

"The camera does not bring anything close to you; it’s only more of the same void that we see. This is also true of television, and the movies… you’re simply looking through a window. Cubism is a much more involved form of vision. It’s a better way of depicting reality, and I think it’s a truer way… You can sense when a picture is not felt through space."

Hockney explored this subject again in 1985 in his drawing Ian Watching Television which, though conceived as an independent work of art, would serve as the basis for the present work two years later. Slightly smaller than the eventual painting, the drawing demonstrated Hockney’s desire to envelop the viewer into the scene by his use of multiple vanishing points. This sense of illusionistic space is underscored by the unsteady lines that crisscross the picture and the dark rhombus that floats behind Falconer’s head. The figure has three legs—a nod to David, Celia, Stephen and Ian, August 1982—and an organically shaped hand with a cigarette perched between his fingers. His face, deeply shadowed on one side, is well articulated, as is the lounge chair that seems to envelop him. The television is only recognizable as such from the title; a casual observer might think it no more than a congruence of unparallel lines. Taken as a whole, the drawing is a fascinating study of Cubist portraiture, but does not fulfill Hockney’s desire to bring his portraits into the “real world,” or rather, to bring the viewer into his portraits. Hockney attributed this fault to the lack of color, observing during a visit made to his studio by Peter Weber, his biographer, that in his most successful works of this period the “intensity of the tones and the bold shapes make the edges of the canvases disappear. So the picture leaps out at you. It all comes from my Xeroxes, working in layers and with collages. I am making your eyes move about… If you can make the eye move about, you make the viewer aware of the element of time, and so time and space will be interconnected.” (The artist quoted in: Peter Webb, Portrait of David Hockney, New York 1988, pp. 234-35)

Right: HENRY MATISSE, YOUNG SAILOR II, 1906 IMAGE © THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART. IMAGE SOURCE: ART RESOURCE, NY ART © 2021 SUCCESSION H. MATISSE / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

The following year, inspired by his studies in stage design and his Xerox collages, Hockney revisited his portrait of Falconer. As powerfully evidenced in the present work, Hockney now knew how to make the picture leap out at the viewer. The present work, like David, Celia, Stephen and Ian, August 1982, is primarily painted in black and red, with blues incorporated as highlights and a soft yellow to depict Falconer’s short, blonde hair. His Picasso-esque hand (cigarette still dangling) is a bright, peachy tone that stands in stark contrast to the rest of his body, which is bathed in blues and purples. There is no single vanishing point, but rather multiple white lines that radiate from the different angles of the television represent both the shafts of light emanating from it and the varying viewpoints from which one could view the scene if one was standing in the living room too. The lounge chair has expanded beyond the border of the picture, while the edges of the canvas appear to recede— we are there, watching television with Falconer, whose cigarette laden hand also functions as a compositional pivot for the painting; Hockney is not only depicting an object from multiple perspectives simultaneously but asks that the viewer change their approach in order to see the scene in a different way. Speaking about Picasso’s Cubist work in 1983, Hockney observed, “People complain when they see a portrait by Picasso with three eyes, they say ‘But people don’t have three eyes!’ It’s much simpler than that. It’s not that the person has three eyes, it’s that one of the eyes was seen twice.” (David Hockney, Lecture at the Victoria & Albert Museum, November 1983, p. 21) Similarly, in the present work, Ian does not have three legs – one leg has simply been seen twice. Continuing his conversation with Weber in his studio in 1986, Hockney described: “So you have to understand that physics and art are closely related. It’s amazing that the art world doesn’t seem to have woken up to that yet… The philosophical basis of quantum physics is that there is no such thing as a neutral viewpoint. It has to be a participatory viewpoint. Well, Cubism is like that—putting our bodies back into space. It’s about you, you are a part of it, not outside it.” (Op. cit., p. 235)

“Every time you look, there’s something different. Again, the figure is painted differently each time […] He’s still looking. Each time, he’s seeing different things. Here is a painting clearly about weight, about volume, in the way some are not. They’re about something else. There’s a thousand subjects. There’s a thousand ways of seeing."

Ian Watching Television is a triumph of looking. In 1984, Hockley had delivered a talk on the great paintings of the 1960s at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and devoted it entirely to Picasso. Flipping through Christian Zervos’ catalogue raisonné, Hockney wondered at the infinite variety of Picasso’s portraits: “Every time you look, there’s something different. Again, the figure is painted differently each time […] He’s still looking. Each time, he’s seeing different things. Here is a painting clearly about weight, about volume, in the way some are not. They’re about something else. There’s a thousand subjects. There’s a thousand ways of seeing… one must look, one must look, one must look, and the more one looks, the more variety there is.” (David Hockney, Picasso: Paintings of the 1960s, 3 March 1984, Reel-to-Reel Collection A0004, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York) The present work represents the apex of Hockney’s reinterpretation of Picasso’s Cubism, whilst also referencing Futurism’s fascination with depicting movement in stasis.

Ian Watching Television speaks directly to Hockney’s life-long study of what the artist referred to as “methods of depiction,”, and the profound influence of changing cultural visual mediums, with the television dominant at that time. Hockney playfully leaves the screen itself blank, but nods to the mesmerizing effects of television through the shafts of light that fly towards Falconer’s face. The Cubist elements of the picture therefore have another function in this work: to suggest the experience of movement and time while watching, as Ian fidgets and shifts his way through his program. In depicting the act of watching television in the language of Cubism, Hockney demonstrates one of his key artistic beliefs, that painting, and Cubism in particular, can illustrate space in a way that the camera cannot; in his words, “the camera does not bring anything close to you; it’s only more of the same void that we see. This is also true of television, and the movies… you’re simply looking through a window. Cubism is a much more involved form of vision. It’s a better way of depicting reality, and I think it’s a truer way… You can sense when a picture is not felt through space” (Op. cit.) The present work represents a unique opportunity to join Hockney in his joyful studies of physics and art, Cubism and modern photography. Remarkably vibrant and beautifully painted, Ian Watching Television represents a pivotal moment in Hockney’s relentless exploration of methods of representation, and stands among the finest of the artist’s portraits from the 1980s.