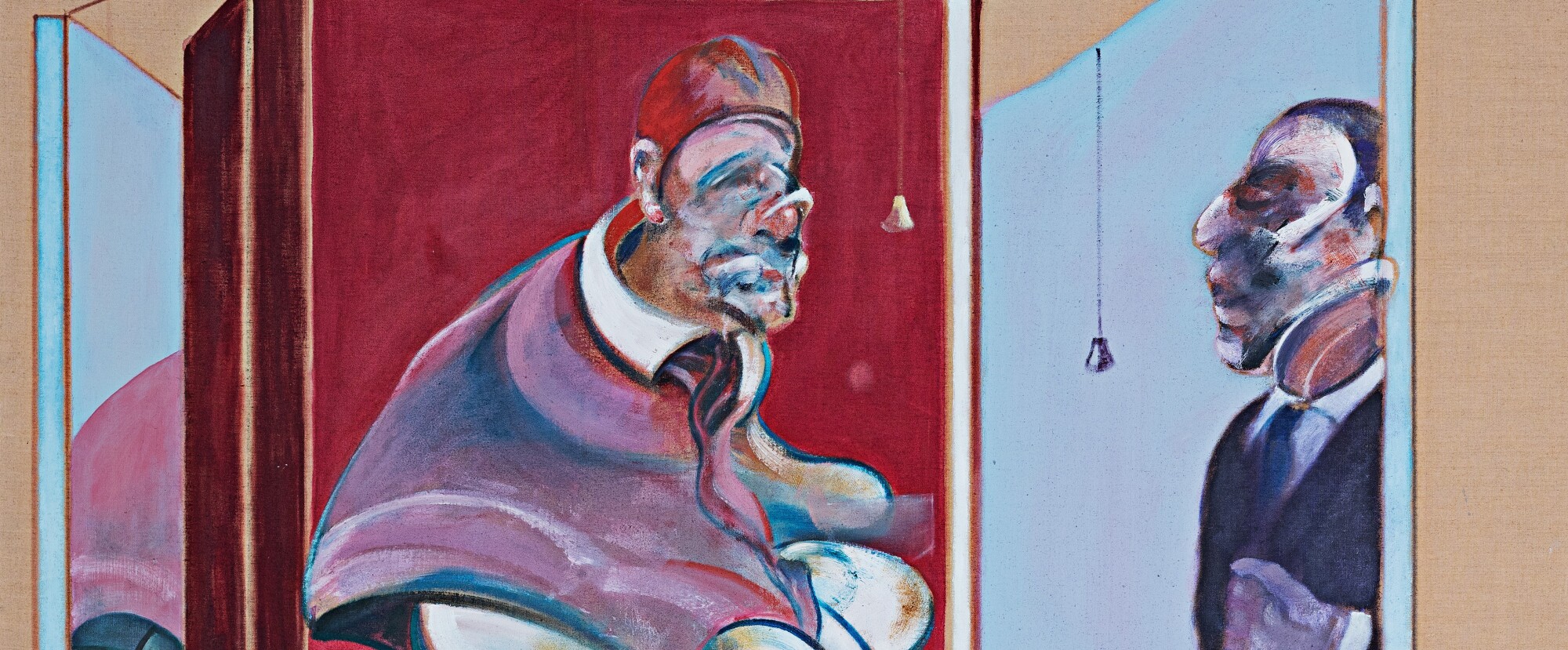

"Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971… is the final work in the series. Once again, Bacon introduces an element that complicates the spatial situation and sharpens the challenge to the viewer's perceptions. The element in question is the mirror, an inherently ambivalent image that can also be read as a window. Here, too, the backrest of the throne has the function of a picture within a picture, but in this case, it is extended to form a triptych, a winged altarpiece whose two side-panels are folded out so that the viewer sees only their inner surface."

A defining masterpiece and triumphant finale to the artist's seminal series of Pope paintings, Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 depicts the first and only encounter within Francis Bacon's oeuvre between his two most important subjects: the Pope raised on a dais, drawn from Diego Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X,1650, and George Dyer, the love of Bacon's life and one of his most celebrated muses. First unveiled at Bacon's landmark retrospective at the Grand Palais in 1971, a career-defining exhibition and an accolade only previously afforded to Pablo Picasso among living painters, Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 remains a testament to Bacon's limitless capacity to provoke and capture the most fundamental of human emotions. In the present work, Bacon reworks the composition of his 1962 painting Study from Innocent X, revising the portrait to include his love George Dyer, as if the figure of the Pope, not only the progenitor of Bacon's practice but a stand-in for authority, the canon, and the father, finds its counterpart in Bacon's lover, instantly identifiable by his curved nose. On October 26th, 1971, the Francis Bacon retrospective opened to great acclaim, the galleries at the Grand Palais were filled with admirers, yet George Dyer's presence was tragically absent. Less than thirty-six hours prior, Dyer had taken his own life in their Paris hotel room. Executed shortly before the Retrospective, Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 reveals a haunting premonition of the devastating loss of Bacon's lifelong love, a singular meeting of his two greatest muses and charts Bacon's artistic maturation between 1962 and 1971. Having remained in private hands since 1972, the present work's importance is further attested to by its inclusion in the major retrospective Francis Bacon Books and Painting at the Centre Pompidou in 2019.

“In the lives of all of us there is a human being whom we least wish to lose. Bacon sustained that particular loss at the time of his retrospective exhibition in Paris in 1971-1972. He bore it with a stoicism for which even Homer would have been hard put to find words; but in his real-life – his life as a painter, that is to say – it came to the fore over and over again.”

A tragic loss and profoundly emotional soul, Dyer was often portrayed in Bacon's oeuvre as in motion or in a mirror. As John Russell describes: "A compact and chunky force of nature, with a vivid and highly unparsonical turn of phrase, he embodied a pent-up energy... a spirit of mischief, touched at times by melancholia... his wild humour, his sense of life as a gamble and the alarm system that had been bred into him from boyhood... George Dyer will live forever in the iconography of the English face." (John Russell, Francis Bacon, London 1993, pp. 160-65) Dyer's passing would continue to haunt Francis Bacon's artwork throughout his career. A now legendary portrait, Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 is one of the last images Bacon made of Dyer prior to his death, embodying Bacon's fervent attempt to find catharsis in the canvas. Bacon's portraits of George Dyer are some of his most passionate and psychologically arresting paintings; the spectral figures incisively convey the dichotomously tortured and heroic, romantic and tempestuous nature of their relationship.

Dyer and Bacon met in the fall of 1963 for the first time at a Soho pub; Dyer famously introduced himself to the artist's party with the gambit "You all seem to be having a good time. Can I buy you a drink?" (Jonathan Fryer, Soho in the Fifties and Sixties, London 1998, p. 9) A charming, handsome man, Dyer would soon become Bacon's lover and muse. Underneath this beautiful façade, however, Dyer was deeply conflicted and vulnerable. Their relationship was passionate and tumultuous, tender and brutal. Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 reflects on the eight years they had together, the artistic and emotional transformation Francis Bacon encountered following their meeting in late 1963. During this period, Bacon sought to capture Dyer's likeness with a painterly dynamism that captured his inner turmoil and the mercurial, fierce passion of their relationship. In Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971, Dyer meets the Pope from behind a mirror; he resembles a trapped spectral reflection under that stirring gaze. A macabre and disquieting prophecy, Bacon illustrates Dyer as a shadow, a memory trapped stoically behind the glass, a seminal meeting with the conflicted head of the Catholic Church.

Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 endures as a fervidly fraught and harrowing grande finale to the incomparably momentous series of pontiffs that Bacon obsessively reworked in the 1950s and 1960s, transmitting a palpable vulnerability through the profound aesthetic translation of their psychological tension into painted form. "In any one period, there are only a finite number of images with almost limitless connotations. In our time, along with perhaps Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon, Duchamp's La Grande Verre and a Giacommeti Femme debout, Bacon's Popes are not only the centerpiece of all his paintings...but a centerpiece of the whole of twentieth-century art." (Michael Peppiatt, Exh. Cat., Norwich, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (and travelling), Francis Bacon in the 1950s, 2006, p. 28) A titan of twentieth-century portraiture and one of the most iconic bodies of work, Bacon's Pope paintings were inspired by Diego Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1650.

Bacon was deeply affected by the work, which he described to David Sylvester as "one of the greatest portraits to have ever been made" (Interviews, the green edition, p. 26), and the series became his most famous arena for the rendering of flesh in all its tactile glory and psychological deconstruction. Bacon's chosen task in painting the Pope was not one of representing an image but rather re-representing the meanings inherent to Velázquez's portrait: stature, presence, public role and the very mechanics of being. Bacon gets under the skin and goes beyond the surface of the image, engaging a series of emotions that lie at the heart of ordinary daily existence in the most extraordinary way.

A symbol of authority and power, the Pope that Bacon illustrates, distorts the infallibility of the figure. In many portraits, he is seen erupting in screams, writhing or disfigured. Through his depictions of the Pope, which he began after he first came across a reproduction of Velásquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X around 1946, Bacon would launch an exploration of the nature of existence that would guide his portraiture throughout his career, including those of George Dyer. In Velásquez's portrait, Bacon became infatuated by the raw and tormented figure he glimpsed, a poignant juxtaposition to the figure's exalted status.

"Bacon's mirrors can be anything you like - except a reflecting surface... Bacon does not experience the mirror in the same way as Lewis Carroll. The body enters the mirror and lodges itself inside it, itself and its shadow. Hence the fascination: nothing is behind the mirror, everything is inside it."

A retired army captain and racehorse trainer with a puritanical and vindictive streak, Bacon's father Eddy tyrannized the family household, and in particular his son, with whom he was at odds. Allergic to his father's horses, asthmatic and unashamedly effeminate, Bacon was expelled from the family home after being caught admiring himself in the mirror wearing his mother's underwear. That the Pope – the Holy Father – was to be Bacon's first subject when he reached artistic maturity is perhaps in part owing to a working-through of personal trauma. Bacon created approximately 50 canvases in the series of Popes, including early works from 1946 to 1950, which he subsequently destroyed, depicting Pope Innocent X, a man afflicted by the weight of his own authority. In the 1960s, Bacon turned to some of his most arresting and intensely captivating muse, his great love.

In 1971, for the retrospective Francis Bacon at the Grand Palais, the artist revised two of his most celebrated works, the present work and Second Version of 'Painting' 1946 (1971), held in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Bacon's insistence that this image be included in the exhibition, despite its then owner's refusal to lend it, coupled with the new inclusion of the intimate portrayal of an emotionally fraught George Dyer, evidences Bacon's regard for the importance of this piece and composition. Together Study for Innocent X and Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 chart the changes in technique, form and style that Bacon employed over the intervening nine years; the Baroque richness of color evident in his 1962 painting differs from the sparingly applied paint and raw canvas in Bacon's later work.

The dynamic passages of painterly strokes of impasto juxtaposed against the bare canvas highlight the dramaturgy of the composition, the curved mirrors and fragmented space almost seem to foreshadow the iconic Black Triptychs executed following Dyer's death. Furthermore, the inclusion of George Dyer evidences a palpable emotional reverence. Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 elevates the personal to the universal, transmitting a palpable vulnerability and arresting intensity. The work marked the end of an era for both muses, the final papal portrait and one of the last portraits of Dyer prior to his death; the light cords that dangle between them are suspenseful and threatening, a premonition of Dyer's death. Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971 singularly embodies the profound artistic reckoning between 1962 and 1971, becoming the ultimate encapsulation of Bacon's most transformative decade.

As Wieland Schmied describes, "Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971… is the final work in the series. Once again, Bacon introduces an element that complicates the spatial situation and sharpens the challenge to the viewer's perceptions. The element in question is the mirror, an inherently ambivalent image that can also be read as a window. Here, too, the backrest of the throne has the function of a picture within a picture, but in this case, it is extended to form a triptych, a winged altarpiece whose two side-panels are folded out so that the viewer sees only their inner surface." (Wieland Schmied, Francis Bacon, CITY 2006, p. 23) Bacon worked from printed photographs of both the Velásquez Pope and Dyer, disfiguring and morphing their images to illustrate the burden and complexities of their internal psyche. He felt that by referring to secondary sources, he was able to remove their literal appearance and instead capture the essence of their selves. Equally conflicted characters, wrestling with power and vulnerability, the Pope and Dyer meet in the present work confronting each other's gaze with a binding intensity.

One of the most radical iconoclasts, Bacon's obsession with the Pope and Dyer, both fundamentally impacted his oeuvre and, more broadly, twentieth-century painting. Coupled together in the present composition, akin to a devotional diptych, the Pope and Dyer's figures appear twisted, fractured and densely worked. Together, united as subjects of Bacon's painterly obsession, they deftly embody the fragility of the human experience. In Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971, the reference to his painting from nine years earlier offers unique insight into Bacon's artistic evolution in the intervening years, a period that marked the most important decade in his life, culminating with the Grand Palais retrospective. Through Study of Red Pope 1962, 2nd version 1971, Bacon is in dialogue with himself, his muse, his lover, his past and his present, rendering a sublime commentary on the human condition with a fervent passion and incisive vigor. Staging the encounter between his great love, Dyer, and his greatest obsession, the Pope, Francis Bacon reveals a tragic premonition of Dyer's fateful passing and a seminal reverent homage to his two most renowned muses finally united together.