“You really were able to capture not only the profound sense of looking at someone but also the someone else looking out into the world.”

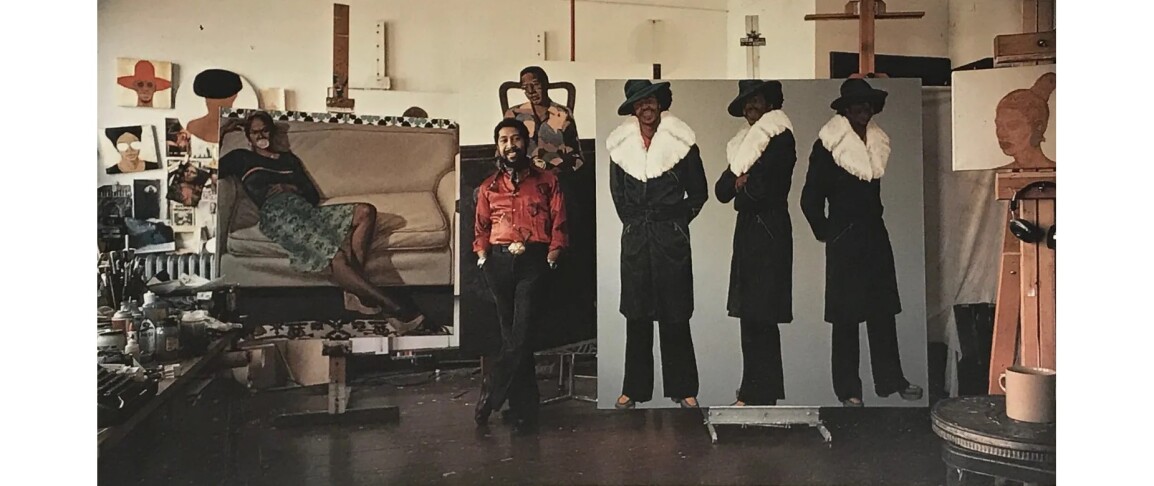

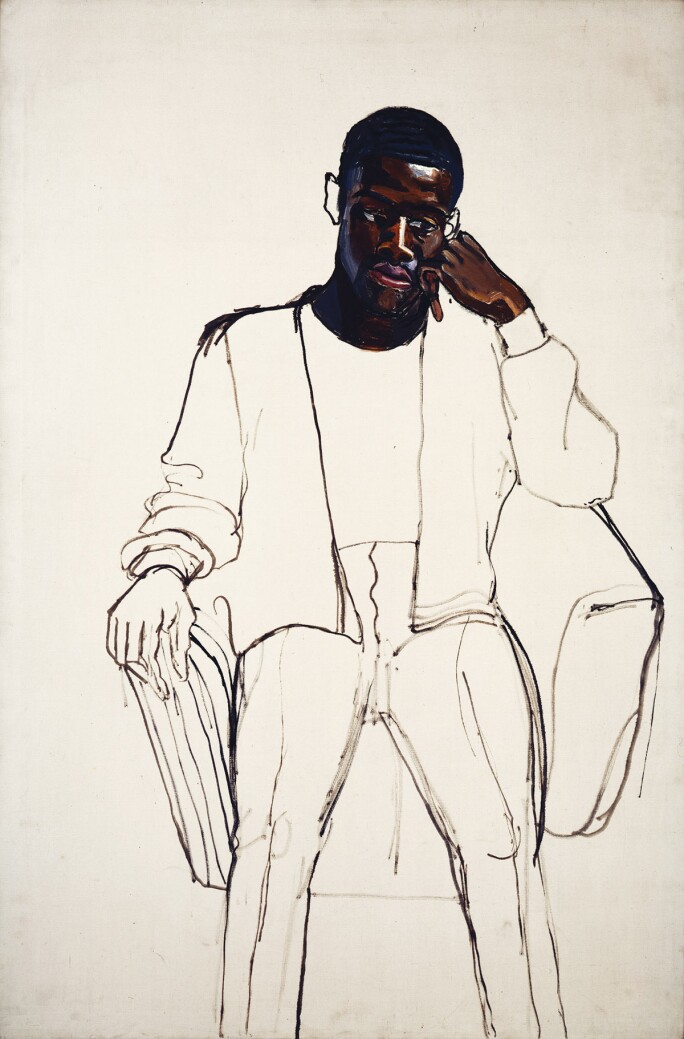

Applying the technical virtuosity of the Old Masters to his deeply intimate depictions of contemporary Black culture, Barkley Hendricks’ Yocks of 1975 is the consummate exemplar of the larger-than-life portraiture for which the artist is best known. At a time when figuration had fallen out of vogue, Hendricks forged a distinct style, poised between the playfulness of Pop, the critical gravitas of Conceptual art and the incandescent theatricality of the Baroque. Pulling models from the closest possible circles—peers, family, friends, strangers who had grabbed his attention on the street, himself—Hendricks treats each with the same reverence, amity, and deft painterly touch. Unbothered in attitude and statuesque in stance, the highly individuated figures of Yocks exude a comfort, coolness, and vitality unique to Hendricks’s subjects. Shown at a heroic scale, the pair exude an immediate confidence and undeniable elegance, assertively redressing the absence of people of color in the canon of portrait painting. Hendricks produced up to six canvases a year at his most active but largely halted his painting practice from 1984 to 2002, during which time he dedicated his attention to photography; within his limited yet incontestably historic oeuvre, paintings of this caliber and scale are highlights of such esteemed institutional collections as the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and the Studio Museum, Harlem. Hendricks is presently being honored in the highly anticipated survey, Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick, which presents his portraits alongside the titans of Western art that Hendricks himself drew inspiration from, such as Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Gainsborough— further cementing his and his subjects’ place within the annals of art history.

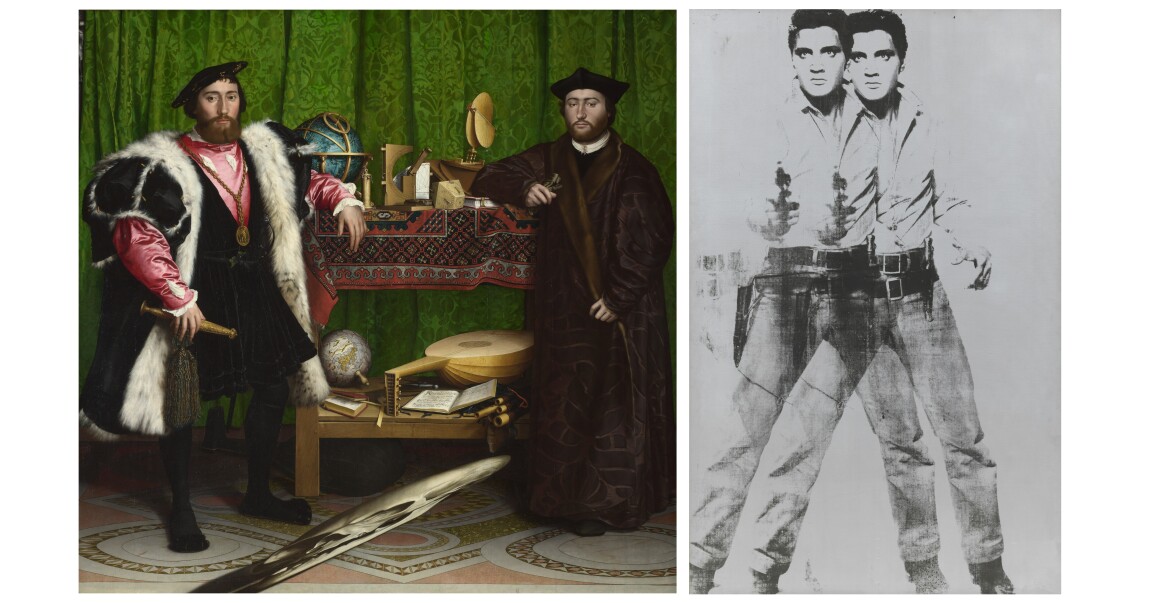

Born in Philadelphia in 1945, Hendricks attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts—a period that would catalyze the development of his artistic style. As a student, Hendricks was awarded two scholarships which allowed him to visit the creative centers of Europe, and it was during those years that he observed firsthand Hans Holbein the Younger’s treatment of fabric and drapery and Gustav Klimt’s revolutionary placement of three-dimensional figures before luminous flat grounds. Upon his return, Hendricks applied these influences to the kin and community around him, depicting his friends, family and larger network in shimmering verisimilitude against monochromatic planes. In the present work, every detail and distinct texture of their dress are articulated with exacting precision, from the fur collar to the quilted leather to the cork-soled platform boots. Set against a velvety field of decadent acrylic white, the two figures smile, effortlessly assuming a swaggering contrapposto.

"Where human subjects are concerned, I address what is in front of me."

The influence of Hendricks’ photographic practice is readily apparent in the intentional cropping of the image, recalling the artist’s famous reference to his camera as his ‘sketchpad.’ Even more astounding than the lucid, stunning clarity he is able to achieve with his brush is his ability to capture and depict the aura and attitude of his sitters. Despite the decades passed since their execution, his paintings and the personalities contained in them are as vital and vibrant as ever, influencing a future generation of artists including Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, among countless others. It is the humanity in Hendricks’ work—the charisma expertly captured in paint—that has defined the indelible mark Hendricks has left on postmodern portraiture.

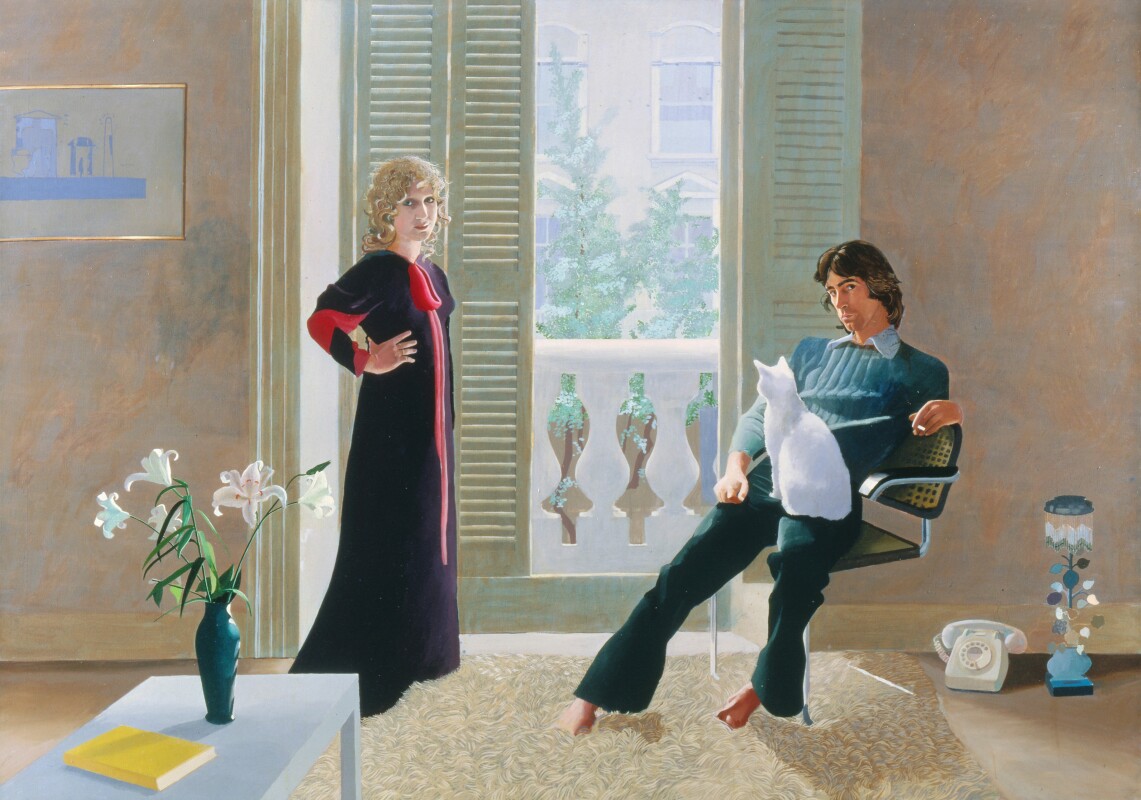

Hendricks based the present work on two men he encountered in Boston, explaining: “There was the shine of the green leather coat and the ‘bling’ of the gold teeth…Yock was the name given to a dude who knew how to ‘rag.’ Rick Powell would call them dandies.” (The artist cited in Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: a Sourcebook of Artists' Writings, Berkeley, 2012, p. 263) Posed, poised and self-assured, Yocks reinvigorates and recontextualizes the Victorian legacy of dandyism, expanding the possibilities of Black male expression. Hendricks’ Yocks stand isolated, and unlike the double portraits of Hockney or Holbein, there is no scene to inhabit: the viewer can attend only to the people before them and is called to interrogate the exclusivity of the history of art. Krista Thompson has remarked on Blackness presenting itself as though it could be “dislodged from a particular space and time and … embodied anywhere.” (quoted in Huey Copeland, “Figures and Grounds: The Art of Barkley L. Hendricks,” Artforum, vol. 47, issue 8, April 2009, p. 148) Here, Hendricks frees his subjects of imposed expectation or assumption. The composition also invokes the aesthetics of Blaxploitation film posters, a film subgenre that emerged in the 1970s from such iconic Black directors as Gordon Parks and William Crain, decidedly centering these self-fashioned men and situating them, too, as heroes in a lineage of Black American visual culture.

A triumph of the artist’s photorealistic technique and representations of Blackness in the Seventies, Yocks characterizes the very best of Hendricks’ output: the coolness of his subjects, the warmth of his brush and the inimitable singularity of his vision. The joy and confidence of the figures radiate in their vivid beauty, style and life-sized stature, one that is palpably embodied and lived day after day. As Hendricks described: “where human subjects are concerned, I address what is in front of me.” (the artist quoted in: Exh. Cat., Durham, Duke University, Nasher Museum of Art (and traveling), Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool, 2008, p. 194)