Lot08 N11625 4CL87

“Once settled, I hope to produce masterpieces”

There are few themes in the history of modern art as celebrated as Claude Monet’s Nymphéas. The very mention of the Impressionist movement invariably conjures images of the lushly rendered water lilies that Monet began painting in the late 1890s and refined until the last years of his life. Executed in a kaleidoscopic palette of jewel-toned purples and luscious blues, energized by the touches of white, pink and yellow used to describe the namesake flowers, the present Nymphéas is an exceptional example of Monet’s deft ability to translate fleeting atmosphere and the protean effects of light into paint. Nymphéas stands as the forerunner of a specific series of water lilies typified by more elaborate backgrounds featuring the nuanced reflections of trees along the opposite bank of the pond. It is precisely on account of the way Monet uses the pond as a technical device to blur the boundary between the real and the reflected that the work takes on its distinctly modern inflection. In its close cropping and all-over painterly effect, the work likewise marks a radical, early foray into abstraction, one which would prove a decisive stylistic inroad for the Abstract Expressionists who, following in Monet’s footsteps, would come to transform the idiom of modern art thirty years later.

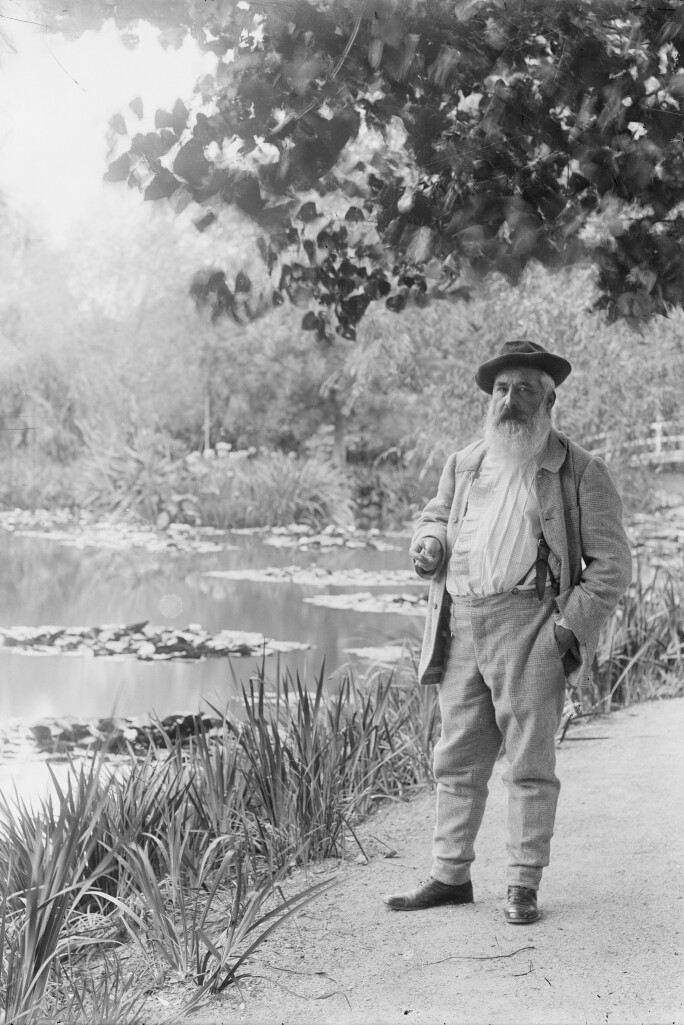

In 1883, Monet purchased his property in Giverny, a small village 50 miles northwest of Paris, and soon began designing the verdant gardens that provided the inspiration for his acclaimed body of late work (see fig. 1). Writing to his dealer and friend Paul Durand-Ruel upon his arrival in Giverny, Monet prophetically proclaimed: “Once settled, I hope to produce masterpieces” (quoted in Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Monet's Years at Giverny, 1978, p. 15-16). In the interplay between nature, atmosphere and the effects of light, Monet found in his pond at Giverny the ultimate Impressionist subject. By the time Monet started on the present work in 1914, however, he had effectively mastered the tenets of Impressionism and begun to move beyond them, marking a shift away from mimetic observation toward an aspiration for the purely atmospheric. In this later period Monet “portrayed the transient so truly that we are forced to conclude that he painted in the absence of his subject... The instantaneity of Monet, far from being passive, requires an unusual power of generalization, of abstraction… Monet declares: here is nature, not as you or I habitually see it, but as you are able to see it, not in this or that particular effect but in others like it” (Michel Butor quoted in Exh. Cat., New York, Gagosian Gallery, Claude Monet: Late Work, 2010, p. 10).

Right: Fig. 2 Claude Monet, Nymphéas, 1906, The Art Institute of Chicago

In 1903, Monet began to dispense with the conventional structures of landscape painting, narrowing his scope to focus directly on the surface of the pond and its reflections. In these earlier works on the theme, the illusion of pictorial depth is upheld by the diminishing forms of the lilies, as they recede towards an invisible horizon. By 1910, however, Monet went a step further to remove any lingering suggestion of perspective. Hovering above his subject from this new vantage point, Monet was presented with an almost flat plane of water and increasingly came to treat the surface of the canvas as if it were a mirror to that of the pond itself. When compared with the 1906 canvas held in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, the transformative effect of this shift in perspective on the overall composition becomes apparent (see fig. 2). Whereas in the 1906 canvas, there maintains a palpable suggestion of perspectival depth, in the present work the group of lilies in the top left and bottom right corners of the work appear almost flat against the water’s surface, rendered from the same scale, distance and angle, just a few degrees shy of a bird’s eye view. The ovoid lily pads offer the only suggestion of a recession in space, as opposed to the circular shape they would take when seen directly from above. The distorted perspective is heightened by the rotation of the horizontal surface of the water onto the vertical orientation of the canvas, distending the composition in a strangely frontal extension. Meanwhile, Monet’s masterful handling of tone in the modulated blue expanse at the center confers the imperceptible depth of the pond onto the painted surface.

As such, the edge of the canvas becomes an indeterminate mediator, at once circumscribing the water within its limits, and, through the cropping of the flowers, suggestive of an endless expanse beyond it. As the viewer levitates atop the work’s surface, the result is a quality akin to the sublime. A philosophy tracing back to the 1st century, the sublime was repopularized by 19th century Romantic painters who used it to create landscapes in which the viewer was utterly subsumed by the incomprehensible breadth and majesty of nature. What was achieved through the awe-inspiring vastness of Caspar David Friedrich’s 1824 Evening is here achieved through the reverse pictorial tool—through the proliferating magnitude of the pond seen from up close (see fig. 3). As Georges Clemenceau, a long-time friend and supporter of Monet’s, observes: “All the radiating energy of the sky and earth is thus summoned to appear before us for the unutterable stupefaction of a show, wherein the joys of dreams and the freshness of primitive sensation merge. One senses an unfailing aspiration for the infinite from the most subtle sensations of tangible reality, which spread from reflection to reflection, until they reach the ultimate shades of what is imperceptible” (Georges Clemenceau quoted in Exh. Cat., Paris, Centre Culturel du Marais, Claude Monet at the Time of Giverny, 1983, p. 187).

“This interplay between flatness and depth, between art and illusion, gives these pictures much of their dynamism, allowing the artist to develop their decorative possibilities without ever losing sight of their origins in nature”

In both its composition and size, the present Nymphéas marks a radical shift in Monet’s approach to a subject which, both at the time and in posterity, has come to be regarded as one of the most celebrated motifs in his canonical oeuvre. Measuring a remarkable 68 by 51 inches, the work is a towering example of the monumental canvases which would come to populate his late output. Larger canvases like that of the present work allowed the artist to explore the Nymphéas theme with a freedom of expression that was otherwise restricted by his earlier, smaller scale. The resulting close chromatic range and all-over composition, which heralded a shift from the painterly conventions of its time, prophetically anticipates the origins of the large-scale gestural canvases of the later New York School. According to William Rubin, the masterpieces of this later generation, particularly the monumental canvases of Jackson Pollock, the father of Abstract Expressionism, “are related to the late Monets not only in aspects of their plasticity but in their intimacy, a quality they share with the wall-size pictures of Rothko, Newman and Still” (William Rubin, “Jackson Pollock and the Modern Tradition, Part II,” Artforum, February 1967, p. 18).

Right: Fig. 5 Clyfford Still, 1953, 1953. Tate Modern, London

In the years after World War II, Monet’s garden at Giverny and his paintings in Paris became a site of pilgrimage for young American artists studying in France. Among them was Ellsworth Kelly, who saw dozens of the artist’s unsold works on a visit to Giverny in 1952. So taken by their scale and gestural brushwork, Kelly painted his own sweeping green canvas, Tableau Vert, as an homage to Monet (see fig. 4). A kinship can also be felt in Clyfford Still’s 1953, wherein the hints of red along the lower edge, like the water lilies in the present work, are used to contrast and in turn emphasize the depths of the blue filling the rest of the canvas (see fig. 5). Kelly’s attention to the acute differences in shade and tone likewise echo Monet’s sensitivity to the chromatic effects of light on the pond’s surface.

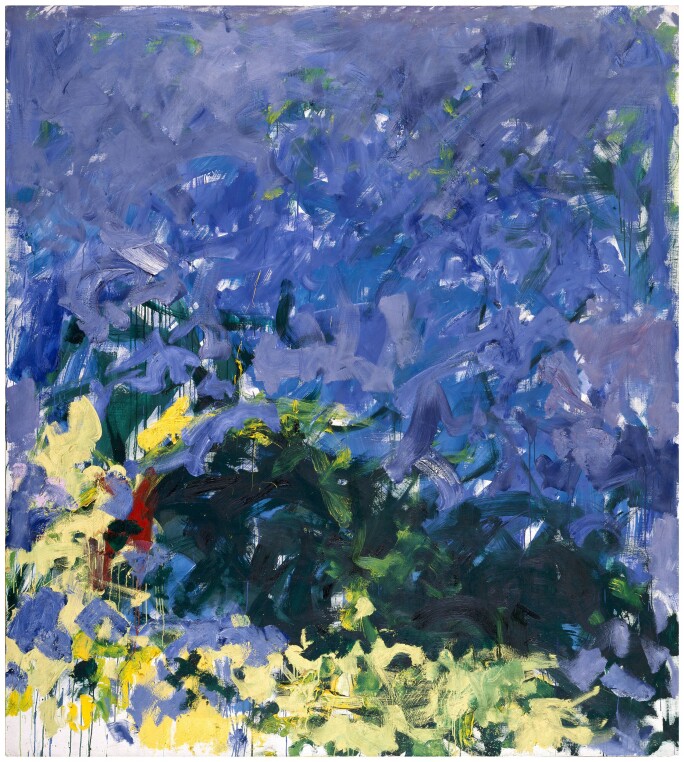

But the most immediate influence may be seen in the work of Joan Mitchell, whose immersive abstractions of the French landscape are deeply indebted to Monet. In 1955, Mitchell began dividing her time between New York and France where in 1968 she moved permanently, buying a home just a few miles from Monet’s in Giverny. La Grande Vallée V (see fig. 6), executed in 1983, stands as a striking compositional parallel to the present Nymphéas. Here Mitchell translates Monet’s subtle painterly style into her distinctive abstract vocabulary. The hints of green scattered throughout the periwinkle brushstrokes filling the upper register echo Monet’s careful study of the trees reflected on the pond, while the yellow brushstrokes, climbing up from the bottom of the canvas, offer a reinterpretation of the water lilies themselves. When examined from up close, however, Monet’s staccato brushwork, particularly his rendering of the flowers, has the same Expressionist affectation as Mitchell’s. In dialogue, it becomes clear that the present Nymphéas and the larger body of Monet's late works offered the last remnants of figuration before modern art dissolved into pure abstraction.

"Late Monet is a mirror in which the future can be read. The generation that, in about 1950, rediscovered it, also taught us how to see it for ourselves. And it was Monet who allowed us to recognize this generation. Osmosis occurred between them. The old man, mad about color, drunk with sensation, fighting with time so as to abolish it and place it in the space that sets it free, atomizing it into a sumptuous bouquet and creating a complete film of a 'beyond painting' remains of consequential relevance today.”

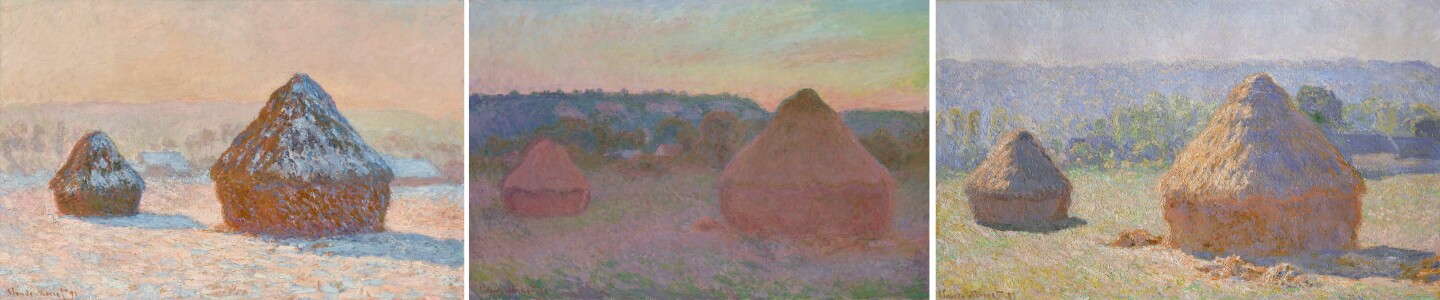

Beyond the revolutionary leap into abstraction Monet takes with the present work, his predilection for the serial study of a subject likewise serves as a prescient forerunner to the practice of later generations of artists. The repeated investigation into the same motif was echoed and abstracted, for example, in the works of Mark Rothko, who later elevated the planes of color in Monet’s work from the scale of the brushstroke to that of the canvas. Rothko himself elaborates on the impact Monet had on his own work: “Direct awareness of an essential humanity can be found in my work. Monet had this quality, and that is why I prefer him” (James Breslin, Mark Rothko: A Biography, Chicago, 2012, p. 301). The distinctly Abstract Expressionist conception of an artwork as the transcription of the artist’s emotions through the recorded movement of their hand, can likewise be understood as a direct development of Monet’s preoccupation with capturing a quality of instantaneity—the ultimate ambition of his serial work. As John House explains, “he was seeking a way of translating nature’s most fleeting effects into fully realized, complete works of art. No longer could the impression be an end in itself; the work of art had to transcend the initial experience and yet still retain a sense of the immediacy of the experience, of ‘l'instantanéité’” (John House, “Monet in 1890” in ibid., p. 133). Completed over the last twenty years of his life, Monet’s present series of Nymphéas stands as the culmination of his success within the format.

CENTER: Fig. 8 Claude Monet, Meules, (fin de journée, automne), 1890-91, The Art Institute of Chicago

RIGHT: Fig. 9 Claude Monet, Meules, fin de l’été, 1891, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Image © 2024 Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

The series was a recurring mode of address within the Impressionist lexicon, famously adopted by Camille Pissarro in his repeated study of the Jardin des Tuileries, as it was by Paul Cezanne with his series on Mont Sainte-Victoire. But beginning in the 1890s, with his canonical Meules, Monet distinguished his approach from that of his peers, transforming the “series” from merely a mode of address to a subject in and of itself (see figs. 7-9). When in 1891 Monet chose to exhibit 15 of these early Meules canvases in a solo exhibition at Paul Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery, he decisively introduced the concept of sequence into our understanding of the series. When viewed together, the explicit subject of each canvas shifted from the namesake Meule to the nuanced differences between each representation of it. Qualities of light, atmosphere, weather and tone came to carry substantive weight within the composition as much as its conventional subject matter did. Monet would develop his serial approach through views of the bank of the Seine, Waterloo Bridge and Rouen Cathedral. But in its mature iteration, the series of Nymphéas communicates that momentary quality without need for accompaniment by another canvas. As exemplified by the present work, the subtlety of tonal modulation, fragility of reflection, and overwhelming nuance of spectral chromatism testifies to a fleeting moment captured. The work stands alone, at once an invocation of the broader theme and a testament to the singularity of each canvas within it. Likewise on display, however, is the almost paradoxical effect which comes to define Monet’s late series of work: as he narrows his focus to the meticulous study of a single subject, the scope of that investigation proliferates far beyond a singular motif.

The luminous effect captured in the present work and expounded upon in the broader series, is perhaps best described by the artist himself: “I have painted these water lilies a great deal, modifying my viewpoint each time, transforming the motif according to the season and according to the different light effects that each season brings. Besides, the effect varies constantly, not only from one season to the next, but from one minute to the next, since the water flowers are far from being the whole scene; really they are just the accompaniment. The essence of the motif is the mirror of water whose appearance alters at every moment, thanks to the patches of sky which are reflected in it, and which give it its light and movement. The passing cloud, the freshening breeze, the storm which threatens and breaks, the wind which blows hard and then suddenly abates, the light growing dim and then bright again - so many factors, undetectable to the uninitiated eye, which transforms the colouring and disturb the planes of water” (Claude Monet in François Thiébault-Sisson, “Les Nymphéas de Claude Monet,” Revue de l’art, 1927, p. 44).

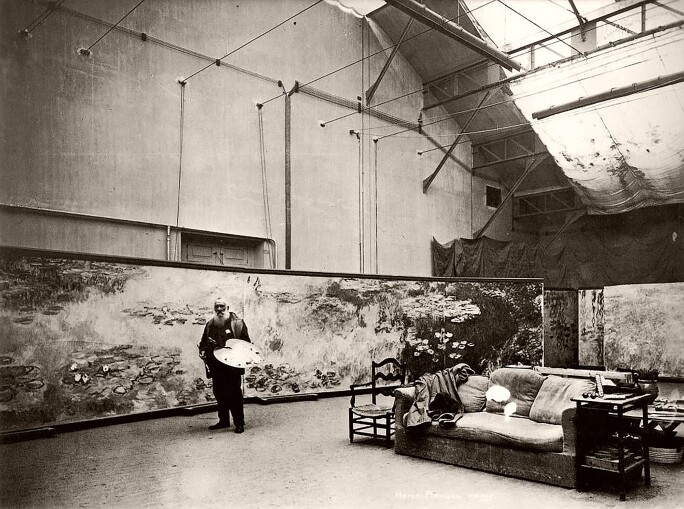

It was on this large scale that Monet first conceived of his water lilies as a decorative motif, a project which would find its culmination in the magnum opus of his Giverny period, the cycle of Grandes décorations. In 1914, the same year that he began work on the present Nymphéas, as the series of canvases on the subject, executed on an increasingly large scale, had come to accumulate within his studio, Monet in turn began placing the different views of his water lilies next to each other in various combinations. One can imagine, for example, the way in which the present composition might figure into the larger expanse of water directly to the left of Monet as he stands before the working canvas in his studio at Giverny (see fig. 11). With these Grand décorations, Monet envisioned an artwork which would immerse his viewer in the proliferating world of his painted water lilies as he himself was in his gardens at Giverny. The final murals would bring the abstraction pioneered in the present work to its apogee, striking a remarkable harmony between figuration and decoration, observation and experience.

Monet tried tirelessly to secure the gift of his Grandes décorations to France as a commemoration of the end of the war; protracted negotiations led by Georges Clemenceau over the official donation to the French state went on for years. Decisions about the permanent location of these works in Paris were discussed and changed multiple times. Meanwhile, the Grandes décorations remained in the artist’s large studio until his death, as in his last years he found himself unable to part with them. Some months after his passing, the works were moved from Giverny to Paris where each canvas was photographed in the Cours Visconti at the Musée du Louvre. They were then formally transferred to the Orangerie in 1927. Initially built as a winter greenhouse to shelter the Jardin des Tuileries orange trees, the Orangerie had been expressly redesigned to receive Monet’s magnum opus. The works were mounted in two oval-shaped rooms, and lit, as Monet specified, in as close a way to natural light as possible (see fig. 11). There they remain today, hung in perpetuity as a monument to the anecdotal moment.

“It took me some time to understand my water lilies. I had planted them for pleasure; I cultivated them without thinking of painting them. A landscape does not sink in to you all at once. And then, suddenly, I had the revelation of the magic of my pond. I took up my palette. Since then I have hardly had another model.”

All of the revolutionary pictorial strides Monet here pioneers with Nymphéas can, at the most fundamental level, by traced back to this unadulterated devotion to the study of his pond at Giverny. Each nuance of tone and subtlety of light testifies to an eye so acutely familiar with its subject that even its most ephemeral qualities become intrinsic. It is precisely on account of the depth of his understanding of the play of light and atmosphere on the water’s surface that he is able to push its representation to the brink of abstraction and still retain the recognizability which resonates so potently within the viewer. Executed in the twilight of his life, the present Nymphéas can therefore be understood as the accumulated effect of observation—not simply over the course of the sitting in which Monet painted it, but over the decades of study which preceded it.

The Museum Context: Claude Monet’s Monumental Nymphéas