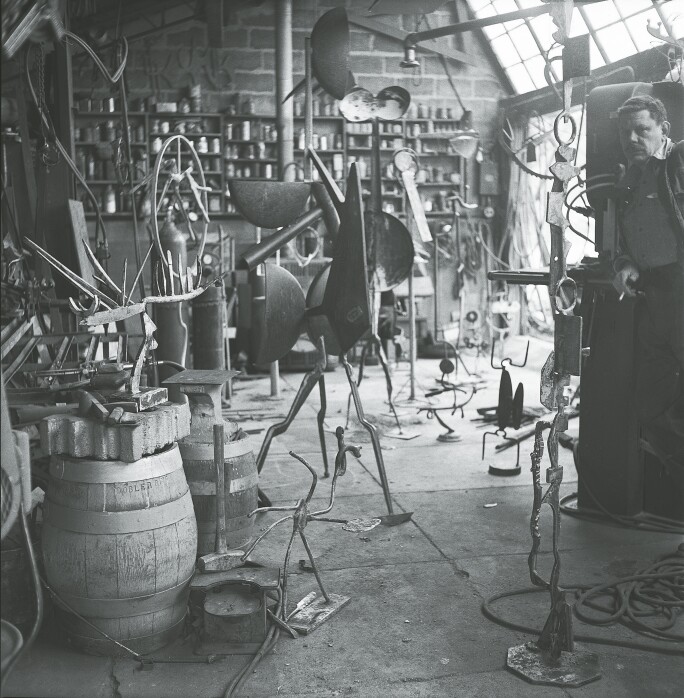

“The Agricola series are like new unities whose parts are related to past tools of agriculture. Forms in function are often not appreciated in their context except for their mechanical performance. With time and the passing of their function and a separation of their past, metaphoric changes can take place permitting a new unity, one that is strictly visual.”

I

n its remarkable geometry and thrilling complexity of form, Agricola VII stands as a testament to Smith's profound contribution to Twentieth Century sculpture. The interconnected found elements of Agricola VII conflate Duchampian modes of conceptual thought with the most advanced formal understanding of abstract line and spatial organization. Distinguished by its rich red-painted surface, and having remained in the same esteemed private American collection for the past two decades, Agricola VII superbly reflects Smith's achievement of pushing modernist sculpture toward previously uncharted expressionistic territories. Testifying to the caliber of the present work, it has been included in group and solo exhibitions at such institutions as the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among others; most recently, the present work was featured in the celebrated exhibition The Fields of David Smith at the Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, New York, organized in part by Smith’s daughters and estate.

Agricola VII belongs to a group of seventeen Agricola sculptures that define this seminal moment in Smith’s oeuvre: this is the first series explicitly grouped and titled by the artist, thus inaugurating a method that mapped a powerful trajectory for the rest of his career and culminating in his final great series, the Cubi. Testifying to the singular importance of this group, examples from the Agricola series are held in such museum collections as the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., the Tate Gallery in London, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among others. The term 'Agricola' is a Latin word that translates to “farmer;” appropriately, in Smith’s eponymous series, the primary components are discarded pieces of farm machinery. Smith described his affinity for his chosen material in a 1959 interview:

Agricola Sculptures in Institutional Collections

Smith turned to these everyday materials, at least initially, for their accessibility—his financial restrictions catalyzed an unbridled spurt of creativity and innovation in the Agricolas that preceded his usage of the more expensive steel later employed for his Cubi sculptures. For the artist, materials were of the utmost significance, as the symbolic associations of industrial machine metals such as iron and steel evoked the speed, technology, and progress of modern society. Thus, the work of the artist is to initiate an elevating exchange, whereby the original utility of the individual components is surrendered to a new formal construction. Agricola VII is a superb realization of this process, particularly dynamic in its numerous interlocking parts.

The years 1951-1952 marked the most radical period of the artist’s development, nearly two decades after he made his first steel sculptures; as noted, “By almost all accounts David Smith’s work of 1951 and 1952 marks the dividing line in his oeuvre, separating his sculpture into its early phase and that of its mature career... This particular material [abandoned or disused pieces of farm machinery], in turn, generated a new kind of figuration in Smith’s art, one that would remain at the core of his sculptural thinking until his death.” (E.A. Carmean, Jr., (Is there as essay title? If not would just get rid of Author name)Exh. Cat., Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, David Smith, 1982, p. 69) With his mature works of the 1950s, such as Agricola VII, Smith arrived at his artistic apex; in 1950, Smith received a Guggenheim Fellowship, an in 1951 was included in an important exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was United States delegate to the first São Paulo Bienal. Working contemporaneously with the painters of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, Smith parlayed his masterful proficiency with metal into a radical and invigorating approach to sculpture.

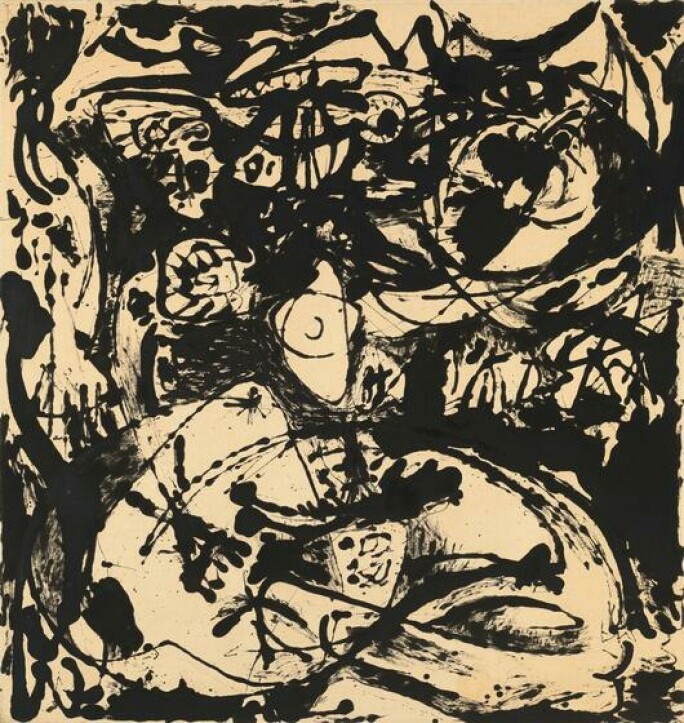

Cunningly expressing the spectacle of nature, the delicate terminations of the metal parts are cast in a new light along with other elements, whose graceful curvature or refined geometry supersedes and obscures their former function. Radically transforming the use value of the found parts of discarded machinery by reducing them to their purely formal, aesthetic, and geometric properties allowed the artist to free sculpture from the plastic arts toward a more transcendental reflexivity. The materials are thereby dematerialized, possessing a grace and purity that forms the essence of Smith’s engagement with the traditions of Modernism and developments in abstraction. Smith actively sought the connection between modern industry and the avant-garde. As he stated in a 1952 radio talk:

“American machine techniques and European cubist tradition, both of this century, are accountable for the new freedom in sculpture-making. Sculpture is no longer limited to the slow carving of marble and long process of bronze. It has found new form and new method… The building up of sculpture from unit parts, the quantity to quality concept, is also an industrial concept, the basis of automobile and machine assembly in the steel process.”

It was in the early 1930s, upon being exposed to the welded iron innovations of Pablo Picasso and Julio González that Smith committed his artistic focus fully to sculpture. In fact, Picasso’s works were first seen by Smith in Cahiers d’Art, and as a teenager while welding in a factory in Indiana, and Smith readily made a direct connection between Picasso’s metal sculptures and his own experiences: “Since I had worked in factories and made parts of automobiles and had worked on telephone lines I saw a chance to make sculpture in a tradition I was rooted in.” (David Smith quoted in: Exh. Cat., Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, David Smith, 1982, p. 20) The tradition of assemblage continued through the additive process visible in the present work, as Smith’s welding of prefabricated units together in an architecture of forms expands the possibility of the sculptural medium.