“It is to be noticed that Pistoletto, instead of accepting the illusion of adding a subjective image within the arc of all the possible representations, has taken from the range of existing images a means of representation that can be verified through visual certainty. Instead of setting out from the blankness of a white canvas, he started with a surface full of images, a mirror…”

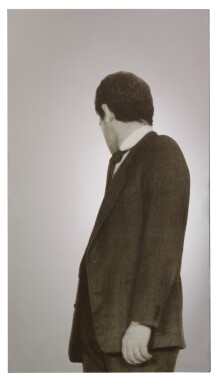

Michelangelo Pistoletto's Maria nuda exemplifies the conceptual rigor and poetic resonance of the artist's iconic Quadri specchianti (Mirror Paintings). Created in 1969, a pivotal year in the artist's career, Maria nuda depicts Maria Pioppi, Pistoletto's muse and partner, in a pose reminiscent of classical art historical precedents like Titian's Venus of Urbino, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres's La Grande Odalisque or Édouard Manet's Olympia. Yet while these earlier icons confronted the viewer with assertive gazes, in the present work, his subject turns inward, absorbed in her own interior world. Her image, fixed via photographic silkscreen on polished stainless steel, coexists with the ever-shifting reflection of the viewer and their surroundings. In this charged juxtaposition, the viewer is no longer merely a spectator but an indispensable element of the work itself.

Pistoletto's breakthrough came in 1961 when, painting a self-portrait on a dark, reflective background, he caught sight of his own face on the surface. What followed was a redefinition of both medium and message. His Quadri specchianti, of which Maria nuda is an iconic example, constitute a rupture in the pictorial field: no longer is the background a passive context but an active site of interaction. "Because when the background started to reflect, to mirror the viewer," Pistoletto later explained, "I decided to make a better reflection with another material: polished stainless steel... The mirror becomes like a film that moves in the present forever and the fixed figure is a photogram of it." (the artist quoted in: Exh. Cat., London, Serpentine Gallery, Michelangelo Pistoletto: The Mirror Of Judgement, 2011, p. 18)

Pistoletto's protagonist is further reminiscent of Diego Velázquez's The Toilet of Venus, which adds a further layer of historical resonance to Maria nuda. Velázquez's reclining nude, depicted with her back to the viewer and gazing into a mirror held by Cupid, invites complex readings of beauty, self-awareness, and voyeurism. In Maria nuda, Pistoletto similarly complicates the act of looking: Pioppi does not return the viewer's gaze but instead becomes a surface upon which the viewer sees themselves. Where Velázquez staged a mediated reflection to hint at the viewer's presence and desire, Pistoletto collapses the layers altogether, merging art, subject, and spectator in a single mirrored continuum. While both works revolve around the female form and the gaze, Pistoletto transforms the mythic and painterly into something deeply self-reflective.

“The mirror paintings could not live without an audience. They were created and re-created according to the movement and to the interventions they reproduced. ... It is less a matter of involving the audience, of letting it participate, as to act on its freedom and on its imagination, to trigger similar liberation mechanisms in people.”

More than a mere technical innovation, the mirror embodies a philosophical proposition: the collapse of the distinction between artwork and the surrounding world, between figure and ground, between image and viewer. In the present work, the image of Maria is still, but the world around her and the viewer within it are in perpetual motion. The result is a work that reconstitutes itself in real-time. Maria nuda becomes a living surface, a generative field in which each viewer sees themselves reflected—not simply physically, but psychologically, doubled, and momentarily transformed. Pistoletto artistic innovations positioned him at the forefront of Arte Povera, the radical Italian movement that rejected both the slick surfaces of American Pop and the tortured expressivity of Post-War abstraction. Arte Povera advocated for a raw, elemental approach to artmaking that engaged directly with time, nature, space, and social conditions. For Pistoletto, the mirror became his "poor" material: not in terms of expense, but in its capacity to democratize the art experience, to reflect back the real, and to implicate the viewer in the artwork.