D7L5K

-

Contemporary ArtFinding Purpose in Art, Identity & the Ocean: In The Studio with Otis Hope Carey

Contemporary ArtFinding Purpose in Art, Identity & the Ocean: In The Studio with Otis Hope Carey -

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story -

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

“Art crystallizes the emotions of an age; art is mirror and voice. The art of our time has to be fundamental, precise, all-inclusive."

The cataclysmic events of the First World War and Russian Revolution were felt keenly in artistic circles across Europe and the newly formed Soviet states in the early 1920s. In Western Europe, the Call to Order ushered in a reevaluation of nascent avant-garde movements in favor of more traditional modes of creation and figuration. In Soviet-dominated regions, a new era of abstraction took hold in the form of the Constructivist and Suprematist movements (see fig. 1). It was within this context that a young Hungarian named László Moholy-Nagy would dedicate himself to achieving societal harmony through creative practice, and masterworks like Am 3 were born.

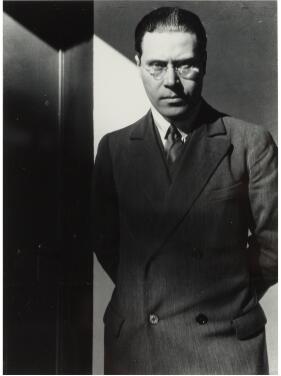

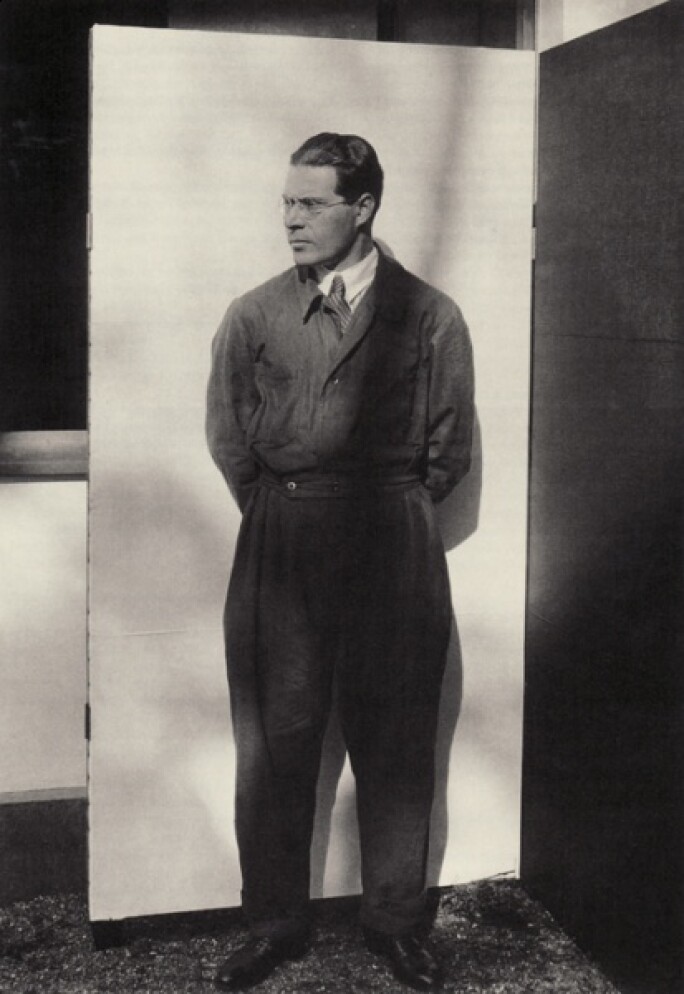

After four brutal years of military service, the twenty-three-year-old László Moholy-Nagy had become disillusioned with the political regimes of the era. His wartime preoccupation with drawing soon seemed like the only clear path toward a better society. Sybil Moholy-Nagy states: "when Moholy finally broke through the confines of tradition, it was not a conscious decision dictated by aesthetic considerations. It was an intuitive need for a solution, peculiar to him and to no one else, which expressed his profound inner transformation during the postwar chaos” (Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Moholy-Nagy, Experiment in Totality, New York, 1950, p. 13).

Injured on the Russian front, Moholy-Nagy spent his convalescence in Budapest dutifully pursuing law studies at the behest of his mother, but also taking art classes. In late 1919, he briefly relocated to Vienna where he joined the staff of the avant-garde journal MA before landing in Berlin in the spring of 1922.

“Even though madness and reaction have followed this revolution, we hope for new human raw material, prepared in the right kind of school-kettles to build and maintain a society dedicated to a totally new culture.”

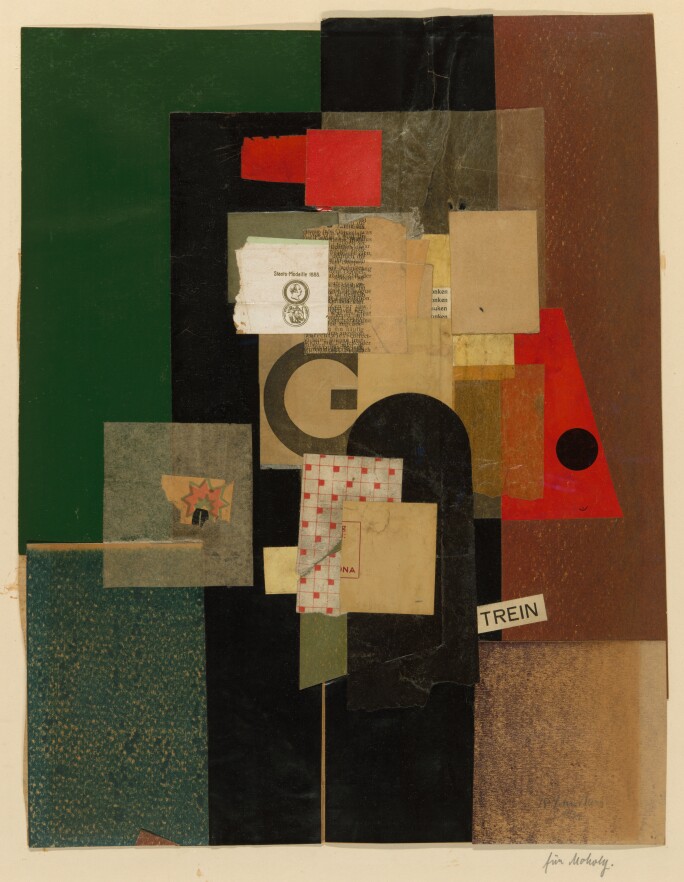

Berlin during the Weimar Republic was a flourishing center of artistic and philosophical dialogues, a place where Eastern and Central European intellectuals and creatives converged. It was here that Moholy-Nagy wholeheartedly engaged with Dada and the Russian avant-garde movements (see fig. 2)—Constructivism in particular. For Moholy-Nagy, this new movement, imbued with the ideological and equalizing promise of communist philosophy, held the key to social progress.

In Berlin, he began to explore the expressive potential of geometric abstraction, industrial materials, and soon, the power of light through the emergence of experimental photography. From Dada, and the works of Kurt Schwitters in particular, Moholy-Nagy gleaned the practice of disassociating symbols—letters, numbers—from their familiar context, recognizing their typographical presence as a formal quality rather than traditional signifier.

However, Moholy-Nagy would never align himself with Dada's sensationalism or its subconscious tendencies, choosing instead to remain committed to his pursuit of societal improvement. The physical practice of collage and application of various elements, on the other hand, sparked a life-long interest in the utility of materials and the intersection of planes. Moholy-Nagy’s own collages from the early 1920s speak to this budding interest and capture motifs which would endure throughout his career (see figs. 3-4).

The influence of Russian Constructivism and El Lissitzky in particular (see fig. 5), was critical to Moholy-Nagy’s evolution as a young artist. In 1920, Lissitzky conceived his first Proun works—an acronym translating to "project for the affirmation of the new'—signaling a new spatial logic that transcended the constraints of painting.

These compositions, ultimately manifesting in multidimensional installations, dissolved the boundaries between architecture, typography, and fine art and suggested an entirely restructured visual and social order—the thesis of which Moholy-Nagy would fully engage with during his later years at the Bauhaus.

"Many men paint Constructivistic, but no ones paints as [Moholy-Nagy] does. Don't talk about coldness, mechanization; this is sensuality refined to its most sublimated expression. It is emotion made world-wide and world-binding."

To the young artist, the Constructivist mandate to create art that served life, rather than merely depicting it, aligned with his own belief in the regenerative power of artistic experimentation. As he wrote in 1922, "Constructivism is neither proletarian nor capitalistic. Constructivism is primordial, without class or ancestor. It expresses the pure form of nature—the direct color, the spatial rhythm, the equilibrium of form" (Moholy-Nagy quoted in ibid., p. 19).

Executed in 1923, the year that Moholy-Nagy would leave Berlin to join Walter Gropius' Bauhaus in Weimar, Am 3 illustrates a moment of synthesis within the artist's oeuvre, when the Constructivist ethos converged with his personal commitment to clarity, structure, and transformation. Moholy-Nagy’s concurrent discovery of the 'photogram' process (see fig. 6)—image-making without the use of a camera—during this period led to increasingly experimental photographic and filmic works. Like his earlier collages, these photograms allowed the artist to manipulate light and transparency in his work, the effects of which were reinterpreted in the overlapping planes of his painting. In Am 3, Moholy-Nagy expertly uses differing hues and varnishes to create planes that seemingly interject and overlap, lending a visual effect of transparency and luminosity through an economy of means. Am 3 achieves the impossibility of transubstantiation—here, Moholy-Nagy has conjured light from mere paint.

Reflecting on this period, Moholy-Nagy writes: "I discovered that composition is directed by an unconscious sense of order in regard to the relations of color, shape, position, and often by a geometrical correspondence of elements… I eliminated the perspective employed in my former paintings, I simplified everything to geometrical shapes, flat unbroken colors; lemon yellow, vermilion, black, white—polar contrasts… Color, which so far I had considered mainly for its illustrative possibilities, was transformed into a force loaded with potential space articulation, and full of emotional qualities” (quoted in ibid., p. 15).

Like his Telephonbild paintings (see fig. 7), Am 3, asserts primacy of form in the service of Constructivist self-effacement and non-objectivity. In spite of Moholy-Nagy's purported detachment, however, the spirit of the artist is keenly felt in the present composition, conveyed in the bravura handling and brilliant command of color and line in Am 3.

The reception to such works from the early 1920s was emphatically positive. In response to the 1922 Der Sturm exhibition of Moholy-Nagy's work, the Frankfurter Zeitung wrote: "It takes discipline to be modern. This is where the artistic and the arty part company. Moholy has the iron discipline of scientist. Many men paint Constructivistic, but no ones paints as he does. Don't talk about coldness, mechanization; this is sensuality refined to its most sublimated expression. It is emotion made world-wide and world-binding" (quoted in ibid., p. 32).

The present work reflects the idealism of the era. With its awesome scale and commanding presence, Am 3 is a triumphant resolution of aesthetic inquiry and is testament to the Moholy-Nagy's sense of artistic responsibility—one not rooted in self-reflection, but in a purposeful commitment to societal betterment. Widely exhibited since the 1950s, this painting has been held in the esteemed collection of Rolf and Margit Weinberg for more than 40 years.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Unveiling The Collection of Rolf and Margit Weinberg