D9SJ5

-

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story -

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's -

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

Geek WeekA 54-Pound Martian Meteorite Just Landed at Sotheby's — But How Did It Get Here?

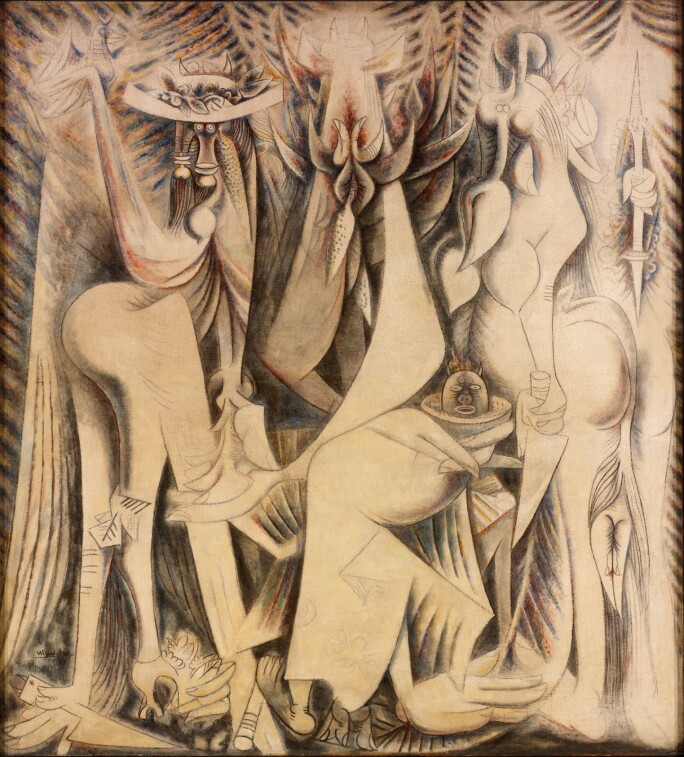

L ’Eau solide is an arresting work from the 1940s—a time marked by Lam's return to Cuba and the rapid integration of Afro-Caribbean culture into his surrealist practice. A haunting tableau of hybrid forms, spectral lines, and chimerical presences, the painting conjures a spiritual landscape where the natural and the supernatural are fused. Positioned at the intersection of European modernist aesthetics and Afro-Caribbean religious cosmologies, L’Eau solide captures the energy of a transformative moment in 20th-century art history while also reflecting the artist’s deeply syncretic worldview.

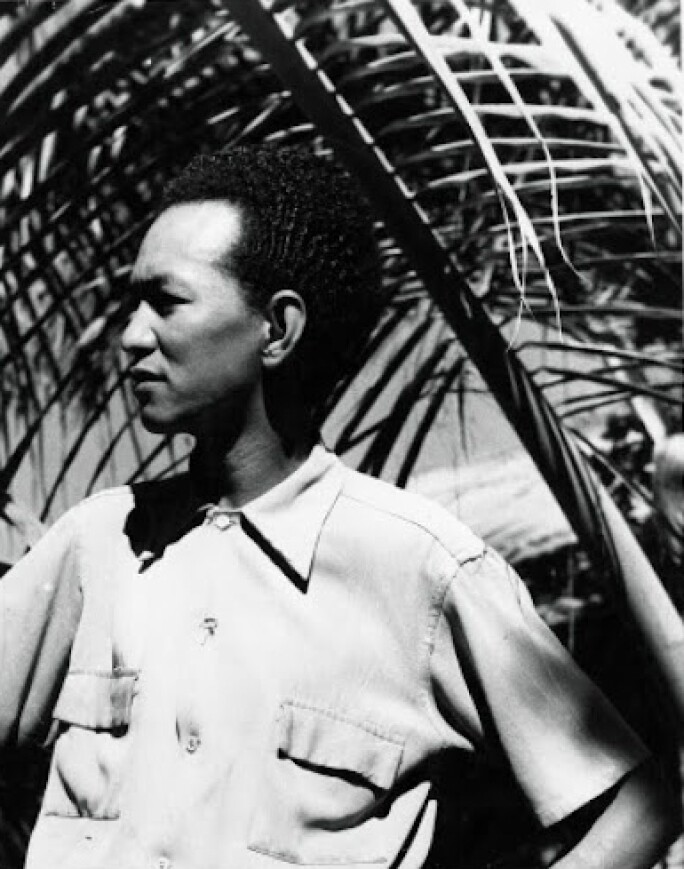

The year 1941 was a turning point in Lam’s life. After two decades in Europe, where he trained in Madrid and later became aligned with the Surrealists in Paris through his association with André Breton, Lam returned to his native Cuba. This return was more than geographical; it was spiritual, ancestral, and ideological. In Cuba, Lam immersed himself in the African diasporic traditions he had known only from a distance in childhood. These included the syncretic religion of Santería, which merged West African Yoruba beliefs with Roman Catholic saints—an act of spiritual resistance and cultural survival in the face of colonial repression. Santería became a source of inspiration for Lam, allowing him to reconnect with his ancestral roots as the son of a Chinese father and a mother of African and Spanish descent.

Lam’s years in Europe were formative, especially his immersion in Surrealist circles. Breton praised Lam as a vital new voice in the movement and recognized in his work a unique confluence of psychic automatism and ethnographic force. Unlike the European Surrealists, who often exoticized non-Western cultures from afar, Lam sought to reclaim and reenergize African diasporic traditions from within. He was acutely aware of the colonialist gaze embedded in European primitivism and worked to invert it. In a 1943 letter, Lam wrote that he wanted to "convey a sense of the African spirit in the Americas" and “to disturb the dreams of the exploiters."

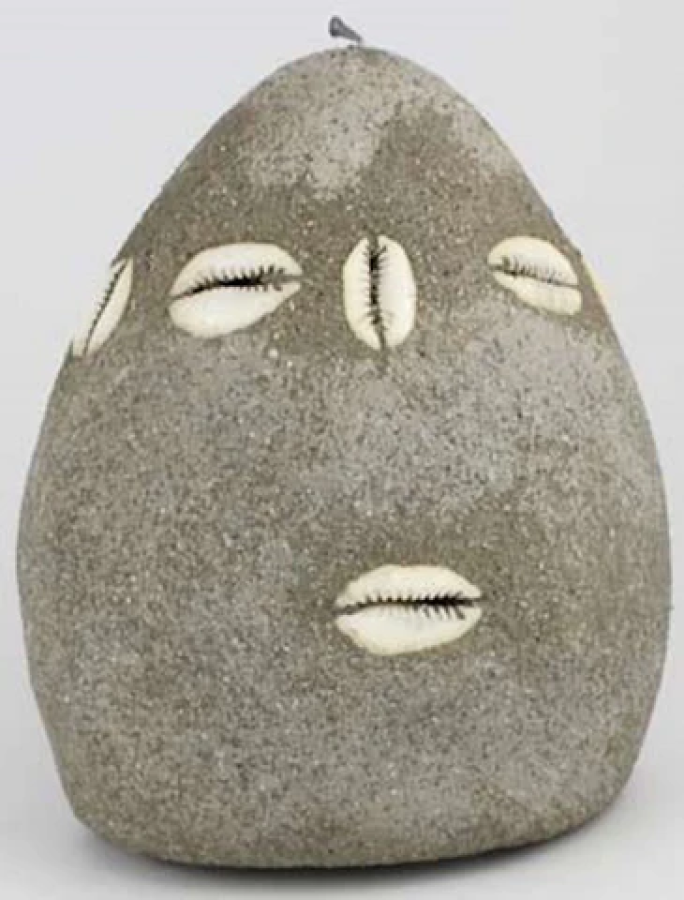

In L’Eau solide, the influence of Santería is palpable in the hybrid, totemic figures that dominate the composition. The horizontal format and mirrored arrangement of forms create a spectral symmetry, with two primary totemic figures appearing in an intertwined, almost combative embrace. The central form—a towering, humanoid creature with elongated limbs and horn-like protrusions—recalls the orishas, the deities of Santería, who often manifest as intermediaries between the human and spiritual realms. The figure’s eyes and jagged mouth evoke Elegua, the trickster orisha associated with crossroads and destiny, whose presence in Santería iconography often signifies transformation and duality. Lam’s use of sharp, angular lines and a muted palette of greens, grays, and ochres further enhances the otherworldly quality of these figures, grounding them in the earthy mysticism of Afro-Cuban spirituality while retaining the dreamlike ambiguity of surrealism.

This cultural integration is made manifest through the presence of other biomorphic forms that blur distinctions between human, animal, vegetal, and divine. These figures appear simultaneously in motion and arrested, echoing trance states or possession rituals within Afro-Caribbean spiritual ceremonies. The wide, mask-like eyes, elongated limbs, and beak-like appendages also evoke the visual grammar of African statuary, which Lam studied in Paris and which permeated modernist collections from Picasso to Giacometti.

The title, L’Eau solide, or solid water in French, suggests a paradoxical substance—neither ice nor liquid, but an alchemical fusion of states. It gestures metaphorically toward a metaphysical realm where fluidity and fixity coexist, an apt image for Santería’s dynamic spiritual world. Lam renders this vision not through literal depiction but through metamorphic abstraction, relying on the tension between opacity and transparency, density and lightness, form and dissolution. Similarly, the palette of L’Eau solide recalls Lam’s surrealist period, particularly his use of earthy tones punctuated by bursts of white and red, a technique seen in works like The Eternal Presence (1944). The few red accents in L’Eau solide, particularly at the edges of the central figure’s limbs, may symbolize the spiritual energy of blood, a common motif in Santería rituals where offerings are made to the orishas. This chromatic choice creates a stark contrast with the muted background, drawing the viewer’s eye to the dynamic interplay of forms and enhancing the painting’s sense of tension and vitality.

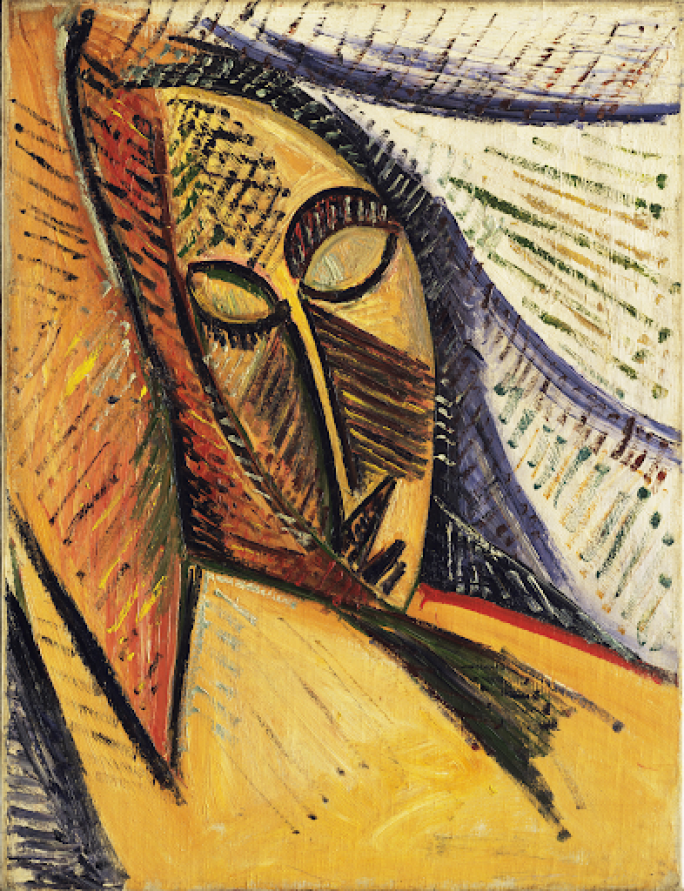

An outstanding work from this important period, L’Eau solide a testament to the artist’s singular vision, one that bridges the surrealist imagination with the rich cultural tapestry of the Afro-Caribbean world. Through its integration of Santería symbolism, its dynamic composition offers a profound meditation on identity, spirituality, and the legacies of colonialism. In L’Eau solide, the viewer sees the confluence of Picasso’s fragmentation, Miró’s surreal biomorphism, and African sculpture’s spiritual geometry—all transformed into something unmistakably Lam’s own. Unlike the European avant-garde, which often oscillated between abstraction and figuration as formal concerns, Lam’s hybridity had ontological stakes: it reflected his vision of a world where categories—racial, spiritual, political—were always already entangled.

In the fall of 2025, the Museum of Modern Art will open a groundbreaking retrospective of Wifredo Lam's career; the first by a major United States institution in decades. It is poised to position the artist as a quintessential transnational artist of the 20th century; not peripheral to modernism, but central in its global project.