Property from the Phillips Collection Sold to Benefit Future Acquisitions

Georges Seurat

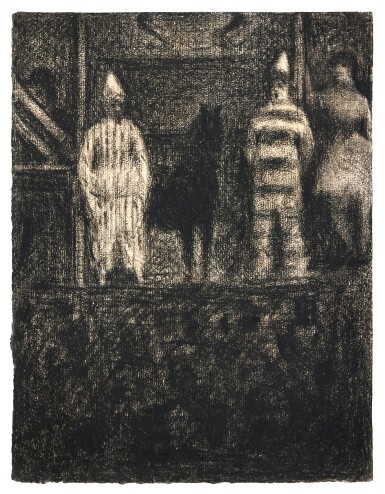

Clowns et poney

Auction Closed

November 21, 01:55 AM GMT

Estimate

3,000,000 - 5,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Phillips Collection Sold to Benefit Future Acquisitions

Georges Seurat

(1859 - 1891)

Clowns et poney

Conté crayon and estompe on paper

12 ½ by 9 ⅝ in. 31.6 by 24.4 cm.

Executed in 1883-84.

(probably) Joris-Karl Huysmans, Paris

Galerie Barbazanges (Camille Hodebert), Paris

De Hauke & Co. (Jacques Seligmann & Co.), New York

Acquired from the above on 26 June 1939 by the present owner

Paris, 1 rue Laffitte, 8ème Exposition de peinture, 1886, no. 181 (titled Une parade)

Buffalo, Albright Art Gallery, The Nineteenth Century: French Art In Retrospect 1800-1900, 1932, no. 94 (titled Study for “La Parade”)

Cambridge, Fogg Art Museum, Style and Technique, 1936, no. 31, pl. XIV, illustrated

New York, Jacques Seligmann & Co., The Stage, 1939, no. 26, p. 28 (titled Study for “La Parade”)

Washington, D.C., Phillips Memorial Gallery, 19th and 20th Century Prints and Drawings, 1943, no. 16 (titled Study for “La Parade”)

New York, American British Art Center, Exhibition of Drawings of the 19th and 20th Centuries, 1944. no. 32 (titled Study for La Parade)

New York, Buchholz Gallery, Seurat: His Drawings, 1947, no. 12 (titled Parade and dated circa 1882)

New York, Knoedler Galleries, Seurat 1859-1891: Paintings and Drawings, 1949, no. 33, illustrated (titled La Parade and dated circa 1882)

The Art Institute of Chicago and New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Seurat: Paintings and Drawings, 1958, no. 134, pp. 24 and 33; p. 76, illustrated (titled Drawing for La Parade and dated about 1886)

Bloomington, Indiana University Art Museum, The Academic Tradition: An Exhibition of Nineteenth-Century French Drawings, 1968, no. 97, p. 34; illustrated (titled Study for La Parade)

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Picasso: The Saltimbanques, 1980-81, no. 12, fig. 11, p. 24, illustrated; p. 86 (titled First Study for “La Parade de Cirque” and dated circa 1886)

Milwaukee Art Center; Columbus Art Museum and Albany, New York State Museum, Center Ring, The Artist: Two Centuries of Circus Art, 1981-82, no. 89, pp. 19 and 93; p. 23, illustrated (titled La Parade (Study))

Tokyo, The Nihonbashi Takashimaya Art Galleries and Nara Prefectural Museum of Art, Impressionism and The Modern Vision: Master Paintings from The Phillips Collection, 1983, no. 44, p. 91, illustrated in color; p. 197 (titled First Study for ‘La Parade’ and dated 1887-88)

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Paris, Grand Palais, Seurat 1859-1891, 1991-92, no. 45, p. 68, illustrated in color; pp. 170, 266, 312, 315-16 and 380-81 (titled Une parade; Clowns et poney) (New York only)

New York, IBM Gallery of Science and Art, Paintings and Drawings from the Phillips Collection, 1983-84, no. 90 (titled Study for “La Parade” and dated circa 1887-88)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte,” 2004, no. 32, pp. 118 and 273; p. 120, illustrated in color (titled Sidewalk Show)

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Georges Seurat: The Drawings, 2007-08, no. 135, p. 244, illustrated in color; p. 254 (titled Sidewalk Show (Une Parade [Clowns et poney]))

Kunsthaus Zürich and Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Georges Seurat: Figure in Space, 2009-10, no. 69, p. 128, illustrated in color; p. 143 (titled Clowns et poney (Une Parade) (Sidewalk Show)) (exhibited in Frankfurt only)

Washington, D.C., The Phillips Collection, Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities: Painting, Poetry, Music, 2014-15, fig. 30, pp. 33 and 179; p. 36, illustrated in color (titled Sidewalk Show)

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Seurat’s Circus Sideshow, 2017, fig. 51, p. 56, illustrated in color; pp. 57-58 and 130 (titled Sidewalk Show (Une Parade) and dated circa 1883-84)

Labruyère, “Les Impressionnistes II,” Le Cri du peuple, vol. 3, no. 942, 28 May 1886, p. 2 (titled Parade)

“Phillips Memorial Gallery,” The Washington Post, 31 December 1939, p. 7 (titled The Parade)

Germain Seligmann, The Drawings of Georges Seurat, New York, 1946, no. 22, pp. 19-21 and 59; pl. XIX, illustrated (titled La Parade and dated circa 1882)

The Phillips Collection, ed., The Phillips Collection Catalogue: A Museum of Modern Art and Its Sources, Washington, D.C., 1952, p. 91; pl. 74, illustrated (titled First Drawing for “The Side Show” and dated circa 1882)

César M. de Hauke, Seurat et son oeuvre, vol. II, Paris, 1961, no. 668, p. 246; p. 247, illustrated (dated circa 1887)

Robert L. Herbert, Seurat’s Drawings, New York, 1962, fig. 108, pp. 123 and 183; p. 124, illustrated (titled Sidewalk Show)

William I. Homer, “Review: Seurat’s Paintings and Drawings,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 105, no. 723, June 1963, p. 283

John Russell, Seurat, New York and Toronto, 1965, no. 188, p. 212, illustrated; p. 283

Pierre Courthion, Georges Seurat, New York, 1968, p. 38, illustrated (titled First Study for “The Side Show” and dated circa 1887)

Japan Art Center, Inc., ed., Seurat et le Néo-Impressionnisme, Tokyo, 1972, pl. V, illustrated

Fiorella Minervino, Tout l’oeuvre peint de Seurat, Paris, 1973, no. D 54, p. 107, illustrated (dated 1887)

Exh. Cat., Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874-1886, 1986, p. 446 (in reproduction of Exh. Cat., Paris, 1 rue Laffitte, 8ème Exposition de peinture, 1886)

Masataga Ogama and Takeshi Kashina, Les Peintres Impressionistes 13: Seurat, Tokyo, 1978, pl. IV, illustrated

Exh. Cat., Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Master Drawings from the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1985, p. 156 (dated 1882-83)

Sarane Alexandrian, Seurat, Paris, 1990, p. 87, illustrated; p. 95 (titled Clowns et poney (La Parade) and dated circa 1882)

Alain Madeleine-Perdrillat, Seurat, Geneva, 1990, p. 109, illustrated; p. 213 (titled Clowns and Pony, Study for “Circus Sideshow” and dated circa 1887)

Richard Thomson, Seurat, Oxford and New York, 1990, p. 153

Michael F. Zimmermann, Les Mondes de Seurat, son oeuvre et le débat artistique de son temps, Paris, 1991, no. 490, p. 350; p. 351, illustrated (dated circa 1887)

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting, Impressionism: 1874-1886, vol. II, San Francisco, 1996, no. VIII-181, p. 252; p. 276, illustrated (titled Une Parade)

Paul Smith, Seurat and the Avant-Garde, New Haven and London, 1997, fig. 82, p. 65; p. 66, illustrated (titled Une Parade: clowns et poney)

Robert L. Herbert, Seurat: Drawings and Paintings, New Haven and London, 2001, pl. 24, illustrated; pp. 44, 68 and 83 (titled Sidewalk Show (Une Parade))

Michelle Foa, Georges Seurat: The Art of Vision, New Haven and London, 2015, fig. 82, p. 120, illustrated; p. 121 (titled Parade)

Clowns et poney of 1883-84 evinces Georges Seurat's virtuosity with Conté crayon drawing and affirms his standing as one of the most accomplished draughtsmen in the history of art. An early example of the artist's engagement with popular entertainment and performance, a central theme of his oeuvre, the present work is a crucial precursor to his Pointillist masterwork Parade de cirque, housed in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Drawing occupied a vital and enduring role in Seurat's practice from the earliest years of his career: by the 1880s, the artist wholly dedicated himself to refining his drawing techniques, ceaselessly sketching quotidian scenes and characters from his native Paris and its banlieues. The spectacle of itinerant circuses attracted Seruat, their elaborately costumed performers figuring in his drawings as early as 1881. Clowns et poney, however, marks Seurat's first engagement with the subject of the parade, circus' free sideshow performances intended to entice passers-by into purchasing tickets for the spectacle within. On a platform outside the decorative circus tent, two clowns flaunt a black pony as they bellow to their spectators while a musician and female acrobat, shrouded by the tent's wooden stakes, wait in the periphery for their turn in the spotlight.

Clowns et poney dates to the genesis of the artist's mature drawing practice, defined by his pioneering combination of Conté crayon and thick, textured Michallet paper. Seurat allowed the rich black crayon to only contact the high points of the laid lines of paper, leaving its white grooves untouched, thereby suffusing each drawing with a dazzling luminosity he termed "irradiation." Appropriated from the optic principles of Charles Blanc, Michel-Eugène Chevreul and Eugène Rood, this method of producing minute juxtapositions of light and dark enabled Seurat to experiment with the possibilities of achieving aesthetic harmony through a division of tones, which in turn informed his development of Pointillism. As Gustave Kahn asserted, "On the day Seurat devoted himself to drawing, Neo-Impressionism began" (Gustave Kahn, Les Dessins de Georges Seurat, Paris, 1928, p. ix). Seurat wields this revolutionary technique to ethereal effect: even the darkest passages of the nocturnal scene appear to emanate an internal radiance that invokes the atmospheric diffusion of light from street lamps, a then-novel aspect of urban life.

Eschewing the use of linear contour learned during his early training at the Paris Académie des Beaux-Arts, Seurat models each compositional element through subtle tonal modulations ranging from velvety black to vivid white. Hatches and loops are attentively superimposed in varying densities until, as John Russell describes, "no longer are we conscious of individual pencil strokes, but merely of the process of uninterrupted becoming" (John Russell, Seurat, New York, 1965, pp. 80 and 83). This confluence of line generates a sense of surface movement from which the glowing figures materialize, endowed with a stately, sculptural presence. Displaying Seurat's Rembrandt-esque sensitivity, details from the curve of the clown's hats to the arc of the pony's muzzle emerge through near-imperceptible gradations of value. Offering a foil between viewer and spectacle, the backs of a depersonalized, anonymous audience form the tenebric lower register. At once supremely elegant and poignantly enigmatic, Clowns et poney is instilled with a sense of timelessness.

A fixture of popular culture in fin-de-siècle Paris, the circus was by this time a pervasive subject matter in artistic genres ranging from Naturalist tableaux to satirical illustrations, with the figure of the saltimbanque—carrying tragicomic connotations of alienation and melancholy—made ubiquitous through the likes of famed caricaturist Honoré Daumier (see fig. 1). Seurat, however, deliberately resists such tropes in Clowns et poney: as with his masterworks Une Baignade, Asnières and Un Dimanche après-midi à l'île de la Grande Jatte, a site of social confluence is here used to convey his progressive artistic ideals. Richard Thomson characterizes a similar parade scene as "exemplary in steering a path between the caricatural and the descriptive, suggesting both but taking on the guise of neither...a work that describes a recognizable world but in a way that gives primacy of place to..the gentle effect of the obscure—and returns us to the mysterious fascination of looking" (Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Seurat's Circus Sideshow, 2017-18, p. 105). The present work presages similar engagements with this subject matter by modernists including Picasso, Bonnard, and the Expressionists (see fig. 2).

Clowns et poney is foundational, in both subject matter and composition, to Seurat's 1887-88 masterwork Parade de cirque (see fig. 3). Seurat replicates the schema of the present work, with the brass musicians of the famed Cirque Corvi, staged at the annual seasonal fair of the Foire au pain d'épice, arranged upon a platform in a similarly frontal, frieze-like array above the silhouettes of spectators' backs. Preparatory drawings for Parade de cirque reveal that Seurat toyed with including elements of the present work (such as a black pony) in this painting, that were withheld from the final version. Subjects of popular culture and entertainment preoccupied the artist for the remainder of his career, also constituting the other final two of his six major, multi-figure paintings. The pictorial device of a rear-facing audience in the foreground would reemerge in many of his depictions of performance, notably those of his famed café-concert drawings suite (see fig. 4), while in Le Cirque, the artist's last painting, a clown occupies this position (see fig. 5).

Clowns et poney underscores the indelible impact of Seurat's achievements in drawing, palpable in the works of artists ranging from Gerhard Richter to Sol LeWitt (see fig.. 6). Jodi Hauptman expounds, "Seurat's drawings do something to our eyes...Seurat's melding of Conté and Michallet and its resultant vapor, the Zone and its inhabitants, the murky conditions of the banlieue, the flux and change that is modernity itself—their correspondence comes in offer, as Bridget Riley so beautifully articulates, 'an experience just beyond our visual grasp" (Exh. Cat., New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Georges Seurat: The Drawings, 2007-08, p. 117).

Further testifying to its importance, Clowns et poney was one of three drawings selected by Seurat to accompany his first-ever display of his magnum opus, Un Dimanche après-midi à l'île de la Grande Jatte (see fig. 8), at the eighth and final Impressionist Exhibition of 1886. The present work has belonged to The Phillips Collection since 1939, when founder Duncan Phillips acquired it from storied modern art dealer Germain Seligmann. Since that date, Clowns et poney has figured in numerous major exhibitions of Seurat's work organized by other preeminent museums, most recently The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and The Art Institute of Chicago. The sale of Clowns et poney will support an endowment dedicated to future art acquisitions for The Phillips Collection.

You May Also Like