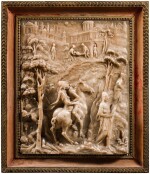

Circle of Jacques du Broeucq (1505-1584), circa 1545

The Good Samaritan | Le Bon Samaritain

Auction Closed

June 14, 01:50 PM GMT

Estimate

15,000 - 25,000 EUR

Lot Details

Description

Circle of Jacques du Broeucq (1505-1584)

Southern Netherlandish,

circa 1545

The Good Samaritan

alabaster relief; in a wooden frame

58 by 45 cm, 22⅘ by 17⅔ in.

____________________________________________

Entourage de Jacques du Broeucq (1505-1584)

Pays-Bas du Sud, vers 1545

Le Bon Samaritain

relief en albâtre ; dans un cadre en bois

58 x 45 cm, 22⅘ x 17⅔ in.

Related Literature / Références bibliographiques

A. Lipinska, Moving Sculptures. Southern Netherlandish Alabasters from the 16th to 17th centuries in Central and Northern Europe, Louvain, Boston, 2014.

R. Didier, Jacques Du Broeucq 1505-1584. Sculpteur et maître-artiste de l'Empereur (1500/1510 - 1584), Bruxelles, 2000.

This magnificent alabaster relief depicts the parable of the Good Samaritan, from the Gospel of Luke. The episode tells of a traveller on his way from Jerusalem to Jericho, who is attacked by robbers and left for dead in the undergrowth. A priest and a Levite pass by, but take no notice and ignore him, under the pretext that they need to fulfil their duties at the temple. St Luke writes: ‘But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him’, promising to reimburse the innkeeper for any expense. (Luke 10: 30-35)

It is this very episode, as recounted by St Luke, that is illustrated in the present relief, reading from the bottom left: The Good Samaritan tends the wounds of the man attacked by robbers, who is huddled beneath a tree, and then carries him away on his horse. In the foreground on the right, the two priests pass them by, on their way to serve at the temple. The architecture in the background suggests the cities of Jericho and Jerusalem, as well as the inn to which the wounded man is carried by the Good Samaritan.

The sculpture’s style and virtuosity is close to alabasters by Jacques du Broeucq (1505-1585), made in about 1545 for the former rood screen in the Cathedral of Sainte-Waudru in Mons.

The quality of this relief recalls the exceptional modelling of the figures, with their elongated proportions and small heads, wearing long tunics that mould to the body in du Broeucq's alabasters. The facial features of the Good Samaritan, though wearing a helmet, can be found in the relief of Pilate washing his hands in Mons. The style of the priests’ clothing – long robes in flowing, almost transparent fabrics – resembles that of the figures in the Gathering of Manna. The trees with their complex branches and dense foliage are an important presence in this work and are very closely comparable to the vegetation in Broeucq’s Garden of Gethsemane.

The artist has given this work great depth, accentuated by the pronounced modelling of the rearing horse seen from the back in the foreground, as well as the plasticity of the trees that frame the scenes, as well as the architecture in the background, creating a fine perspective view into the distance.

The origin of our relief still remains to be determined : It may either have been part of a rood screen in a church in the neighbourhood of Mons,

or it may have belonged to an epitaph in a private chapel.

We are most grateful to Prof. Dr. Aleksandra Lipinska for sharing her observations with us about this work.

______________________________________________

Ce magnifique relief en albâtre illustre la parabole du Bon Samaritain, relatée dans l'Evangile selon Saint Luc. Le récit narre l’histoire d’un voyageur allant de Jéricho à Jérusalem, où il est attaqué par des voleurs et laissé pour mort dans les buissons.

Un prêtre et un lévite passant son chemin, ne s’en préoccupèrent pas et l'ignorèrent, sous prétexte de devoir servir au temple. Saint Luc écrit : ‘mais un Samaritain, (…) étant venu là, fut ému de compassion lorsqu’il le vit. Il s’approcha, et banda ses plaies, en y versant de l’huile et du vin ; puis il le mit sur sa propre monture, le conduisit à une hôtellerie, pour le soigner et promit de revenir pour payer l’aubergiste’.

C’est précisément cet épisode décrit par Saint Luc qui est illustré par notre relief, dont la lecture commence en bas à gauche : Le Bon Samaritain soigne les plaies de l’homme attaqué par les voleurs, recroquevillé sous un arbre, et l’emporte ensuite sur son cheval. Au premier plan à droite, les deux prêtres passent leur chemin pour servir au temple. Parmi les architectures en arrière-plan, on devine les villes de Jéricho et Jérusalem, ainsi que l’auberge où le blessé est transporté par le Bon Samaritain.

Par son style et la virtuosité de la sculpture, notre relief peut être rapproché des albâtres que Jacques du Broeucq (1505-1585) réalise vers 1545 pour l’ancien jubé de la cathédrale Sainte-Waudru, à Mons.

Notre relief se distingue par un modelé exceptionnel des personnages aux proportions allongées, dotés de petites têtes et vêtus de tuniques longues, moulant le corps. On retrouve les traits du visage du Bon Samaritain, coiffé d’un casque, dans le relief de Pilates se lavant les mains à Mons. Le style vestimentaire des prêtres aux robes longues aux tissus fluides, presque transparents, ressemble à celui des figures dans la Récolte de la Manne. Les arbres aux branches élaborés et feuillages denses, occupant une place importante dans notre relief, sont tout à fait comparables à la végétation du Jardin des Oliviers de du Broeucq.

L’artiste a su donner une grande profondeur au relief, accentué par le modelé prononcé du cheval cabré vu de dos, au premier plan, la plasticité des arbres encadrant les scènes, ainsi que les architectures à l’arrière-plan, créant une belle perspective dans le lointain.

Reste à déterminer le lieu d’origine de cette œuvre: aurait il été insérée dans le jubé d’une église voisine de Mons, ou alors figurait il sous forme d’épitaphe dans une chapelle privée ?

Nous remercions Prof. Dr. Aleksandra Lipinska d’avoir partagé avec nous ses observations sur cette œuvre.

You May Also Like