Property from a Private American Collection

Frank Lloyd Wright

An Important and Rare Laylight from the Darwin D. Martin House, Buffalo, New York

Auction Closed

December 8, 07:38 PM GMT

Estimate

150,000 - 250,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private American Collection

Frank Lloyd Wright

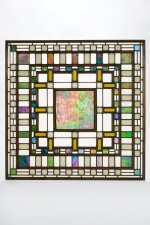

An Important and Rare Laylight from the Darwin D. Martin House, Buffalo, New York

circa 1903-1905

executed by the Linden Glass Company, Chicago, Illinois

leaded iridized, opalescent and clear glass with "colonial" brass-plated cames

26⅛ x 26⅛ in. (66.3 x 66.3 cm)

Mr. and Mrs. Darwin D. Martin, Buffalo, New York

Mr. and Mrs. Darwin R. Martin, Jr., Buffalo, New York

J. Freeman, Northern New York

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1970s

Mr. and Mrs. Darwin R. Martin, Jr., Buffalo, New York

J. Freeman, Northern New York

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1970s

Jack Quinan, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Windows of the Darwin D. Martin House, exh. cat., Burchfield-Penney Art Center, Buffalo State College, Buffalo, NY, 1999, front cover and p. 15

Julie L. Sloan, Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, New York, 2001, p. 167 (for a variant laylight design from the Martin House in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum)

Jack Quinan, Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House: Architecture as Portraiture, New York, 2004, pp. 103, 116, 137 and 167-168 (for period photographs showing laylights installed within the Martin House pier clusters)

Eric Jackson-Forsberg, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Art Glass of the Martin House Complex, San Francisco, 2009, p. 61

Julie L. Sloan, Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, New York, 2001, p. 167 (for a variant laylight design from the Martin House in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum)

Jack Quinan, Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House: Architecture as Portraiture, New York, 2004, pp. 103, 116, 137 and 167-168 (for period photographs showing laylights installed within the Martin House pier clusters)

Eric Jackson-Forsberg, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Art Glass of the Martin House Complex, San Francisco, 2009, p. 61

When Frank Lloyd Wright designed his celebrated house for Darwin D. Martin, he described the entire first floor as a "living room with subdivisions." Those subdivisions were created not by walls, but by structural pier clusters, each with four piers forming the corners of a square. Within each cluster, hidden behind three-quarter brick partitions between each pier, were the heat registers. At eye level, above the brick, were pairs of leaded casement windows that, when opened, permitted heat to enter the rooms. Within each cluster, behind the casement windows, on the ceiling were leaded-glass laylights.

Each laylight—there were originally eight, but most are lost—is constructed of the same materials as the windows: delicate brass-plated cames, opalescent glass, iridescent glass, and clear window glass. The pattern is a condensed version of the so-called Wisteria windows in the living and dining rooms and the library. Myriad rectangular pieces comprise a wide border around a large central square of magnificent iridescent glass set off by a wide band of brass came. Bits of white opalescent glass provide some relief between rectangles of iridescent green glass.

The kaleidoscopic pattern has very little clear glass and is far more intensely colored than any windows in the house, even the famous Tree of Life windows, making the laylights perhaps the most beautiful of the Martin house glass. Wright's selection of glass for the laylights was dictated by the practical issues of lighting in residences which were used both day and night. First, by definition, a laylight receives no direct sunlight and so is illuminated by artificial lighting at night, which required Wright to install an incandescent bulb above each laylight. The bulb must be hidden by the laylight glass, so the design cannot contain much clear glass. The golden light from the bulb flows through the colored glass in tints of mossy green, butterscotch, and amber with dark bands formed by wide caming setting off the design. Wright's second concern was the appearance of the laylight during the day, when the artificial lights were not required. Then the light was not passing through the laylight, but was reflected from it. Light would bounce off the various interior surfaces and strike the glass. Ordinary colored glass would look dull, so Wright indulged his passion for iridescent glass that would reflect the colors of the rainbow, enlivening the recesses of the pier clusters and emphasizing their openness as subdivisions of the whole living room.

—Julie L. Sloan

Each laylight—there were originally eight, but most are lost—is constructed of the same materials as the windows: delicate brass-plated cames, opalescent glass, iridescent glass, and clear window glass. The pattern is a condensed version of the so-called Wisteria windows in the living and dining rooms and the library. Myriad rectangular pieces comprise a wide border around a large central square of magnificent iridescent glass set off by a wide band of brass came. Bits of white opalescent glass provide some relief between rectangles of iridescent green glass.

The kaleidoscopic pattern has very little clear glass and is far more intensely colored than any windows in the house, even the famous Tree of Life windows, making the laylights perhaps the most beautiful of the Martin house glass. Wright's selection of glass for the laylights was dictated by the practical issues of lighting in residences which were used both day and night. First, by definition, a laylight receives no direct sunlight and so is illuminated by artificial lighting at night, which required Wright to install an incandescent bulb above each laylight. The bulb must be hidden by the laylight glass, so the design cannot contain much clear glass. The golden light from the bulb flows through the colored glass in tints of mossy green, butterscotch, and amber with dark bands formed by wide caming setting off the design. Wright's second concern was the appearance of the laylight during the day, when the artificial lights were not required. Then the light was not passing through the laylight, but was reflected from it. Light would bounce off the various interior surfaces and strike the glass. Ordinary colored glass would look dull, so Wright indulged his passion for iridescent glass that would reflect the colors of the rainbow, enlivening the recesses of the pier clusters and emphasizing their openness as subdivisions of the whole living room.

—Julie L. Sloan

You May Also Like