The United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights | The author of the Declaration of Independence witnesses the Ratification of the Bill of Rights

Auction Closed

July 21, 02:20 PM GMT

Estimate

1,000,000 - 2,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

The United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights

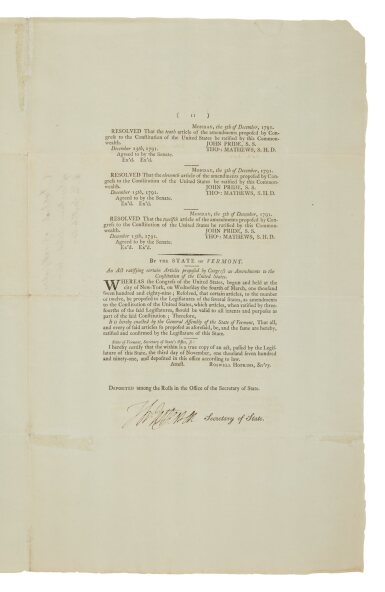

[Congress of the United States: Begun and held at the City of New-York, on Wednesday the fourth of March, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-nine. The Conventions of a number of the States having at the time of their adopting the Constitution expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the government will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution—Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives … Articles in Addition to, and Amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America, proposed by the Congress, and ratified by the Legislatures of the several States, pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution. … Deposited among the Rolls in the Office of the Secretary of State. {Philadelphia: Printed by Childs and Swaine, 1792}]

Final 2 leaves only (of 6), being gathering C comprising pages 9–11 of the text and final blank page (412 x 249 mm, uncut) on a bifolium of fine laid paper (watermarked Posthorn | HS Sandy Run), signed by Thomas Jefferson ("Th: Jefferson") at the foot of page 11, below the letterpress attestment "Deposited among the Rolls in the Office of the Secretary of State," docketed on final, blank page "Duplicate of ratification of Certain Articles added to the Constitution"; separation and neat reinforcements at central fold and horizontal fold creases.

The author of the Declaration of Independence witnesses the Ratification of the Bill of Rights.

An evidently unrecorded and possibly unique—albeit incomplete—authenticated issue of the earliest official printing of the ratified Bill of Rights; the Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin, is unaware of any other copies of this document with the attestation at the end with Jefferson's signature.

"When the first Congress, along with President George Washington, gathered in New York City in 1789, Americans did not assume that the process of constitution-making was now—or ever would be—complete. Many expected the document to be amended almost immediately. Several state conventions had ratified the Constitution with the expectation that their suggestions for its improvement would be taken up and adopted. Most of the proposed amendments grew out of one of the main critiques that Antifederalists such as the Pennsylvania addressers had leveled against the Constitution: that it lacked a bill of rights resembling those attached to most state constitutions. Americans strongly desired guarantees that the federal government would not use its considerable powers to infringe key individual rights. … The Philadelphia convention may not have given much thought to a bill of rights, but it had provided a method by which Americans could add one. Article V of the Constitution outlined the procedure for amending the nation's fundamental law" (Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions, pp. 81–82).

There was no shortage of suggestions as to what a bill of rights should contain. In addition to the provisions of the various state declarations of rights, the ratifying conventions put forth a substantial number of proposals, ranging from South Carolina's four to New York's fifty-seven. The most influential of the proposed amendments originated in Virginia's Ratifying Convention, as described in the preceding lot.

On 4 May 1789, James Madison proposed in the House of Representatives that debate begin on a series of amendments to the Constitution to serve as a bill of rights. Debate began on 8 June and was then referred to a select committee of eleven which, under the close guidance of Madison, created an initial draft that was presented to the House on 28 July. Unlike the present document, that draft was presented as revisions to the text of the Constitution itself, a confusing and ambiguous method that diluted the committee's charge: creating a clearly defined set of rights to be enshrined under the protection of the United States Constitution. On 24 August the proposals were more clearly stated and formatted as "Articles in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America … pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution."

The House's proposed seventeen amendments (attested in print by the House Clerk John Beckley and Senate Secretary Samuel A. Otis) were "printed for the consideration of the Senate," which, through debate and reconciliation, combination and elimination, produced a roster of twelve projected amendments, which was approved by the two houses of congress on 24 and 26 September 1789.

The twelve proposed amendments were ordered to be engrossed on vellum, signed by Speaker of the House Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg and President of the Senate John Adams, attested by the clerk of the House of Representatives and the secretary of the Senate, and transmitted, with a circular covering letter from President George Washington, to the state executives for the consideration of their respective legislatures. Washington's letter, 2 October 1789, stated simply: "In pursuance of the enclosed resolution I have the honor to transmit to your Excellency a copy of the amendments proposed to be added to the Constitution of the United States. I have the honor to be, with due consideration, Your Excellency’s most obedient Servant" (Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Twohig, 4:125).

"The ratification process usually began when the governors submitted messages to their legislatures accompanied by the public documents recently received. … The legislatures often debated the amendments in committees of the whole in which restrictive parliamentary rules were abandoned. Bills adopting some or all of the amendments were drafted and messages between legislative houses were exchanged before agreement was achieved. The bicameral legislatures of Connecticut and Massachusetts, in fact, could not agree on passing the same amendments, consequently neither side submitted certified exemplifications of the amendments that both houses had adopted.

"New Jersey became the first state to adopt the amendments on 20 November 1789. Two weeks later, Georgia’s legislature rejected the amendments as premature. … Maryland and North Carolina ratified in December 1789—the latter only a month after its ratifying convention had adopted the Constitution. Three more states (South Carolina, New Hampshire, and Delaware) ratified the amendments in January 1790. Another three states (New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) ratified by June 1790. With the 1791 ratifications by Vermont and Virginia in November and December, respectively, the necessary three-quarters of the states adopted the amendments" (Bill of Rights 1:465–466.)

The first two proposed amendments actually failed to gain the support of three-quarters of the states, but the proposed third through twelfth amendments were adopted and became the first ten amendments to the Constitution—the Bill of Rights. Oddly, the second proposed amendment "mandated that any pay raises for Congress take effect only after an intervening election. This would prevent legislators from increasing their own salaries immediately. Americans apparently did not consider this issue very important at the time, and the states failed to ratify the amendment. Incredibly, in 1992, after sitting on the books for over two centuries, the proposal finally achieved ratification by more than three-fourths of the (now fifty) states, and it became part of the Constitution as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment" (Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions, p. 86). (And in 1939, the sesquicentennial of their proposal to the states, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Georgia all belatedly ratified the Bill of Rights.)

As the states began to report the results of their deliberations to the executive branch, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson made a tally sheet, on which he kept track of the affirmative or negative (or silent) results of the twelve amendments. When the results from Vermont and Virginia made clear that ten of the amendments had been ratified, Jefferson ordered 135 copies printed of the twelve proposed amendments with the ratification reports of the states. Two copies of this pamphlet, together with other recently approved Acts, were sent by Jefferson to the governors of the fourteen states on 1 March 1792.

Despite this relatively large print run, evidently only five copies are known, and none of these are signed by Jefferson. Copies are located at the Library of Congress, the Maryland Hall of Records, the American Antiquarian Society, the Posner Center at Carnegie Mellon University, and the Samuel Johnston (of South Carolina) copy, whose current location is unknown. Only two of these have ever appeared at auction: the Posner copy was acquired at Parke-Bernet, 25 November 1952, lot 50; while the Samuel Johnston copy was sold at Christie's, 19 December 2002, lot 225. It is worth noting that the Christie's description calls the Johnston copy "uncut, as issued … and the only copy in fine original condition." However, the paper size of the present fragmentary copy is much larger than the Johnston copy (recorded as 13 7/16 x 8 5/16 in.) and was clearly intended for a special purpose.

The present incomplete copy lacks the text of the proposed amendments (pages 1–2) and the ratification reports of New Hampshire, New York, Delaware, Maryland, South Carolina, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and New Jersey (pages 3–8); it retains, in addition to the certifying signature of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, the ratifications of Pennsylvania, Vermont, and, crucially, Virginia.

While the engrossed-on-vellum Bill of Rights on exhibition at the National Archives presents twelve proposed amendments to the Constitution, the present document, albeit fragmentary, memorializes the approval of the first ten amendments to become part of the United States Constitution: the Bill of Rights.

Sotheby's is grateful to John P. Kaminski, Director of the Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin, and co-editor of thirty-five volumes of The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution for reading and commenting on this description.

REFERENCE:

Evidently unrecorded: cf. Bristol B8177; Shipton & Mooney 46596; ESTC W33765 for the standard issue. See also John P. Kaminski, et al., eds. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights XXXVII: Bill of Rights 1, Madison, 2020; James F. Hrdlicka, Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions 14; Vincent L. Eaton, "Bill of Rights," in The New Colophon, II [1949]:279–283.

You May Also Like

![Complete Cycle of Haftarot (Prophetic Readings), [Spain, 14th century]](https://dam.sothebys.com/dam/image/lot/21c5a5f1-1a12-40c9-a8f1-ff1c55cb81fa/primary/extra_small)

![Darwin and Wallace | On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties... , [contained in:] Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society, Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection](https://dam.sothebys.com/dam/image/lot/30891576-117d-4943-b2fa-a8ad164ee5f7/primary/extra_small)