Property from an Important American Collection

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto

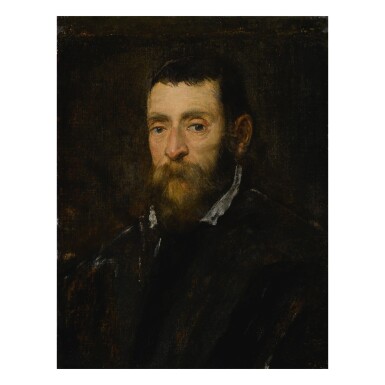

Portrait of a bearded man, possibly Prince Antonio di Santacroce of Rome

Auction Closed

January 28, 04:44 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from an Important American Collection

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto

Venice 1518 - 1594

Portrait of a bearded man, possibly Prince Antonio di Santacroce of Rome

oil on canvas

23 ⅜ by 18 in.; 59.2 by 45.6 cm.

Ian Woodner, New York;

With Stanley Moss, New York;

With Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, New York;

From whom acquired, July 1999.

Of the troika of sublime painters who dominated Venetian art in the 16th Century, it is Tintoretto whose portraits are the most immediate to the modern eye. Compared to the stately and dignified potentates that Titian depicted, or the colorfully dressed Venetian patricians that turned to Veronese, Tintoretto— especially in his smaller, bust-length images— is a much more direct and engaging portraitist. Vasari’s sniffy comment that Tintoretto’s swift technique, performed with “such rapidity, that, when it was thought that he had scarcely begun, he had finished” is simply an observation of exactly the freedom of brushwork that is so admired by a contemporary audience, and that brings the sitters in his canvases so much closer to us today.1This Portrait of a Bearded Man exemplifies exactly this type of portraiture. In it, Tintoretto uses a dark ground on which he captures with a nimble brush the head and shoulders likeness of a soberly dressed man in his early middle age. Except for the face, where the artist uses rapid strokes of pink and ochre to render the sitter’s features and beard, the painting is almost monochromatic. The gentleman’s dress is barely even suggested; subtle tones of black and grey hint at his wide labels and dark sleeves. Slashes of white paint, which still bear the bristle marks of Tintoretto’s brush, form a white linen collar: executed in a moment, it is perfectly understood.

This frankness of the image is reminiscent of a type of bust-length portraiture that Tintoretto produced throughout his entire career, bookended by two of the greatest self-portraits of the Renaissance: his ferocious painting of himself as a young man of 1546/7 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. 1983-190-1), and one painted near the end of his life, circa 1588 (Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 572). In the addendum to her earlier catalogue of Tintoretto’s portraits, Paola Rossi considered the present canvas to be datable to about the same time at the earlier of these, close to 1546, by comparison with the small Portrait of a Bearded Man, painted on panel, signed and dated 1546 (Uffizi, Florence, inv. 1387). Such an early dating for the present portrait, however, seems unlikely; the handling of the Philadelphia Self-Portrait and the Uffizi panel are much more controlled, even allowing for the latter’s support, which lends itself to a higher finish. Rather, the present Portrait of a Bearded Man fits better into the artist’s maturity, the 1550-60’s, when his painterly manner had become more established and accepted. Better comparisons would be the similar bust length Portrait of a dark-bearded, blue-eyed man of circa 1555 or the half-length and more finished Portrait of a young red-bearded man in an armchair of 1558/62, both in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (inv. 350 and inv. 1539).

As with many of Tintoretto’s portraits, we are not sure of the identity of the sitter. Indeed, there is no extraneous visual information to even suggest his social class; he does not wear the senatorial or procuratorial robes sometimes seen in the artist’s half-length portraits. The painting has in the past been identified as Prince Antonio di Santacroce when it was in the Rangoni Machiavelli collection in Modena. The Santacroce were a noble Roman family with fiefdoms throughout central Italy.2

1. G. Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans. G du C. de Vere, 1979, vol. III, p. 1699 [“tanta prestezza, che quando altri non ha pensato a pena che egli abbia cominciato”].

2. While at present we cannot trace the painting further back than the Rangoni Machiavelli collection in Modena, Luisa, daughter of Antonio di Santacroce, Principe di San Gemini, married Aldobrandino Rangoni Machiavelli in 1869, which may prove to be relevant to the earlier provenance of this painting.