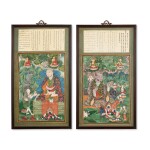

Two imperial thangkas, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, dated to the 58th and 59th years, corresponding to 1793 and 1794 | 清乾隆 御製賓度羅跋羅墮尊者及大乘和尚唐卡一組兩幅 設色布本 鏡框

Premium Lot

Auction Closed

October 13, 04:27 AM GMT

Estimate

4,000,000 - 5,000,000 HKD

Lot Details

Description

Two imperial thangkas

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, dated to the 58th and 59th years, corresponding to 1793 and 1794

清乾隆 御製賓度羅跋羅墮尊者及大乘和尚唐卡一組兩幅

設色布本 鏡框

distemper on cloth, framed; the first depicting Pindola-bharadvaja and the other Hvashang Mahayana, each below Chinese, Manchu, Mongolian and Tibetan inscriptions respectively identifying the figures and dating to the 58th and 59th years of the Qianlong reign, corresponding to 1793 and 1794

82 by 56 cm

A French private collection, acquired in the 1970s.

Portier Paris, 28th April 2010, lot 311.

法國私人收藏,1970年代購藏

巴黎 Portier,2010年4月28日,編號311

These two spectacular Imperial thangkas each depict an arhat, Pindola Bharadvaja and Hvashang Mahayana, as identified by inscriptions in the respective headers written in Chinese, Manchu, Mongolian and Tibetan. Notwithstanding the variation of interpretation on arhatship in different times and regions, in most schools of Buddhism arhats are emulated as venerable examples whose attainments are only inferior to those of Buddhas, permanently liberated from samsara and far advanced along the path of enlightenment.

In a religious sense, arhats are innumerable. In Buddhist scripture and art, however, arhats often appear in groups of a certain number. Among the many existent versions in history, groups of ten, sixteen, eighteen and five hundred are more prevalent, although in sutras arhats only appear in groups of sixteen. An early Tibetan text, Yingqing Zunzhe, records that sixteen arhats were invited from India to preach the Dharma in China during the reign of Emperor Suzong (756-762) in the Tang dynasty. Having accomplished their mission of giving sermons, the sixteen arhats journeyed southwest to Tibet. The Tibetan tradition abides strictly by the Buddhist canons and deifies the Sixteen Arhats, while a sinicised tradition of eighteen is also widely adhered to.

Sets of twenty-three thangkas, comprising one centrepiece of Shakyamuni Buddha flanked by the Eighteen Arhats and the Four Heavenly Kings, were commissioned by the Qing rulers and enshrined within the Forbidden City as an imperial convention. Zhongzheng Dian (the Hall of Rectitude) near the northwest corner of the Forbidden City was where those thangkas were created upon imperial orders. The creation of thangkas is not merely a form of art but also a Buddhist practice. The Hall of Rectitude enrolled eminent lamas residing at Tibetan monasteries in Beijing to accommodate the imperial wishes for thangkas with their reverent hands, and the lamas, therefore, were entitled “Zhongzheng Dian Huafo Lama (Master Thangka Painters at the Hall of Rectitude)”. References in court archives date the employment of “Zhongzheng Dian Huafo Lama” to the fiftieth year of Qianlong (1785), but extant material artworks attest to a dating no earlier than the fifty-fifth year of Qianlong (1790), when the emperor reached the age of eighty. The vast majority of thangkas created by such masters are presently in the collection of the Palace Museum. It is therefore extremely rare to find these two thangkas in private hands. Furthermore, their inscribed dating to the fifty-eighth year of the reign (1793) for the thangka of Pindola Bharadvaja and the fifty-ninth year (1794) for the thangka of Hvashang Mahayana, is in accordance with the documentation of arhat thangkas housed in the Palace Museum, all dated to the fifty-fifth, fifty-sixth (1791), fifty-eighth, fifty-ninth and sixtieth (1795) years of the Qianlong reign.

Contextualised in a complexity of cultural integration, the iconography of arhats in Tibetan Buddhist art has been ambiguous. Hands holding a sutra, sometimes a censer, and mountain gods paying homage to the arhat are some of the standard iconographical depictions. In this example, Pindola Bharadvaja’s hands are simply rendered in dhyana mudra without any attribute, but a haloed mountain god is featured, offering him a branch of blossoms. The arhat is robed in an elaborate kasaya, and the richness of colours added with the meticulous floral details in gold exhibits an imperial majesty. The mountain god, a benevolent incarnation of a yaksha, wears an animal skin that carries a deep Tibetan influence.

Unlike Pindola Bharadvaja, Hvashang Mahayana is not among the Sixteen Arhats described in sutras but rather an adaption of the semi-historical Chinese monk known as Budai. It is reputed that Hvashang Mahayana escorted the Sixteen Arhats from India all the way into Tibet, and he is therefore venerated as one of the Eighteen Arhats. The current Hvashang Mahayana is depicted with right hand in vitarka mudra and left hand with sacred fruits. On the ground in front of him, a group of boys are celebrating in euphoria: one plays music, several more dance and others hand in offerings to the arhat, each in a different posture. Accompanied by the blissful scene, the arhat sits in such equanimity that, together with his neatly layered robes, dignifies the ambience and inspires awe.

The two thangkas bear some obvious resemblance. Major in composition, both main figures are seated in the middle but off-centre, tilted sideways to invite space for the tableau. The disproportionately small worshippers, be it the single yaksha or the group of boys, are all portrayed as looking up to the main figures, whereby the superiority of the arhats is emphasised. Following the Tibetan tradition, both thangkas are framed by Buddhas or Bodhisattvas within transparent haloes at the upper corners. In addition, coral, lotus blooms and mani jewels in the lower parts are characteristic tributes in the Tibetan imagery. On the other hand, mountains in deep verdure, torrents of a waterfall and scrolls of propitious clouds all suggest an incorporation of Chinese elements. In these two imperial pieces, the combination of Tibetan forms and Chinese styles finds a perfect embodiment.

Compare a thangka of Pindola Bharadvaja preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. Set in an almost identical composition of the current work, the Pindola Bharadvaja is depicted holding a sutra and an alms bowl, revered by two yakshas and offered with a giant lotus of various treasures. The waterfalls in the back and the aureole-like clouds behind the arhat are closely related to the current work. As with the current two thangkas, the Palace Museum example was created at the Hall of Rectitude, though earlier, in the fifty-sixth year of Qianlong (1791); illustrated in Classics of the Forbidden City: Tangka Paintings in the Collection Of the Palace Museum, Palace Museum, Beijing, 2010, pl. 208.

A thangka of Budai can serve as a comparison for the Hvashang Mahayana piece. With a typical Chinese portrayal, the arhat sits in a leisurely pose under a fruitful tree, wearing a loose robe and a gentle smile, and holding prayer beads and a peach. As in the present piece, Budai sees a group of boys playing too. The Budai thangka bears an earlier dating, the fifty-fourth year of Qianlong (1789), but is not a creation of the Hall of Rectitude. It is illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Tangka-Buddhist Painting of Tibet, Shanghai, 2003, pl. 188, and again, op.cit., pl. 234.

See also a further related Hvashang Mahayana thangka in the collection of Shelley and Donald Rubin (accession no. P1996.9.1), Himalayan Art Resources item no. 241. It has a more typical Tibetan rendition, with the arhat depicted seated in a comparable setting, garment undone exposing the bare midriff. The arhat is not only surrounded by joyful boys but also flanked by two goddesses. This eighteenth-century example once belonged to a set of twenty-three thangkas and shares a similarity of religious function to the present thangkas.

此二幅唐卡為乾隆御製,莊重端嚴,依天池滿、蒙、漢、藏四語題文可知,乃繪賓度羅跋羅墮尊者及大乘和尚。尊者,即羅漢,於各時期、各地域呈現各異,然佛教眾多教派皆尊羅漢為永脫輪迴、明心見性之達者,其成就僅次佛陀。

宗教層面,羅漢不可計數,而佛教文獻及藝術中,羅漢多以固定數量成組示人。回溯史料,屢見十羅漢、十六羅漢、十八羅漢、五百羅漢等,然佛經只載十六羅漢。早期藏文文獻《迎請尊者》記,唐肅宗(756-762年在位)曾派高僧迎請十六位尊者自印度來中土宣揚佛法,宣法後,十六尊者西行入藏。藏地傳統謹遵佛教經典,奉十六羅漢,而漢化所得十八羅漢亦廣受尊崇。

清代帝君多造二十三幅一堂羅漢唐卡,在紫禁城中供奉。所謂二十三幅一堂,即以釋迦牟尼佛居正中,十八羅漢分居左右,再以四大天王護持。紫禁城西北角設中正殿,奉旨繪造唐卡。繪造唐卡是藝術創作,更是佛教修行,中正殿召集京中藏傳佛寺喇嘛,以妙手虔心繪造寶相,喇嘛得名「中正殿畫佛喇嘛」。考清宮舊檔,可知中正殿畫佛喇嘛初啟用於乾隆五十年(1785年),然遍覽現存實物,未見中正殿畫佛喇嘛筆下有羅漢唐卡早於乾隆五十五年(1790年),彼時,乾隆已壽登耄耋。中正殿所作唐卡大多存於故宮博物院,此二幅乃私人收藏出,故格外珍罕。依題文可斷,賓度羅跋羅墮尊者唐卡為乾隆五十八年(1793年)造,大乘和尚唐卡為乾隆五十九年(1794年)造,皆與故宮所藏羅漢唐卡記錄相吻合——故宮所藏僅見乾隆五十五年、五十六年(1791年)、五十八年、五十九年及六十年(1795年)。

藏地文化交融,千頭萬緒,藏傳佛教藝術中,羅漢圖像亦無定式。羅漢手持佛經或香爐,有山神進貢,較為常見。此幅唐卡中,賓度羅跋羅墮尊者雙手結禪定印,空無法器,有一山神,帶頭光,捧花枝一束獻於尊者。尊者身披袈裟,華貴色彩飾以描金花紋,彰顯皇家威儀。此山神為夜叉化現,形貌恭善,所著獸皮尤見西藏影響。

與賓度羅跋羅墮尊者不同,大乘和尚非佛經所載十六羅漢之一,而是中土布袋和尚演變而來。據傳,十六羅漢自印度來中土、入西藏,一路皆由大乘和尚護送,因此,大乘和尚位列十八羅漢。此幅唐卡中,大乘和尚右手施安慰印,左手捧聖果,身前有童子若干,歡欣自在。一人奏樂,數人起舞,其餘向羅漢獻寶,姿態各不相同。童子怡悅,羅漢則靜坐沈著,衣袍雍容,平添莊嚴。

此賓度羅跋羅墮尊者唐卡及大乘和尚唐卡頗有相似。羅漢為一幅之主,皆居中靠邊,側身以予畫面空間;進貢人物,不論夜叉一軀或童子一群,均身形縮小,仰望羅漢,凸顯羅漢地位。兩幅同依西藏傳統,於左右上角各加佛或菩薩一尊,以透明光暈圍繞,下方又見珊瑚、蓮花、摩尼珠等藏傳造像典型寶物,而青山、瀑流、祥雲等則為中原繪畫元素,可見,二幅為漢藏融合之典範。

比一賓度羅跋羅墮尊者唐卡,故宮博物院藏。構圖格局與此幅如出一轍,賓度羅跋羅墮尊者右手持經,左手托缽,座前有夜叉兩名,及一碩大蓮花,滿載珍寶。尊者身後祥雲升騰,飛瀑垂流,與此幅大同小異。該故宮例亦為中正殿所繪,然年份稍早,為乾隆五十六年,錄於《故宮經典:故宮唐卡圖典》,故宮博物院,北京,2010年,圖版208。

此大乘和尚唐卡可與一布袋和尚唐卡對比。比例中,布袋和尚呈典型漢地風格,背靠一樹,席地而坐,樹枝碩果累累,坐姿閒適安然,布袋衣袍寬綽,笑容可掬,左手拿念珠,右手抱桃果。布袋身前有童子嬉戲,與此幅大乘和尚唐卡相似。布袋和尚例年份更早,為乾隆五十四年,然非中正殿所出。錄《故宮博物院藏文物珍品大系:藏傳佛教唐卡》,上海,2003年,圖版188,及前述出處,圖版234。

另比一大乘和尚唐卡,魯賓伉儷寶蓄(藏品編號P1996.9.1),喜瑪拉雅藝術資源網編號241。該例雖西藏風格鮮明,然佈景與此幅相近,大乘和尚寬衣袒身, 除童子簇擁在前,更有天女侍奉左右。該例繪於十八世紀,原為二十三幅一堂唐卡之一,其供奉當與此二幅遵同一儀軌。

You May Also Like