Property from the Estate of S. Hallock du Pont, Jr.

N.C. Wyeth

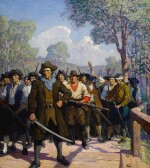

Independence Day (At Concord Bridge)

Auction Closed

November 22, 10:23 PM GMT

Estimate

700,000 - 1,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Estate of S. Hallock du Pont, Jr.

N.C. Wyeth

1882 - 1945

Independence Day (At Concord Bridge)

signed N.C. Wyeth (upper right)

oil on canvas

canvas: 33 ¼ by 30 ¼ inches (84.5 by 76.8 cm)

framed: 41 by 37 ¾ inches (104.1 by 95.8 cm)

Painted in 1921.

Gavin Gail Borden, New York (his grandson, by descent)

M. Knoedler & Co., New York, 1969 (acquired from the above)

J.N. Bartfield Galleries, New York

Acquired by the present owner from the above, 1973

Greenville, South Carolina, Greenville County Museum of Art, N.C. Wyeth, March-May 1974, no. 33

Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, Brandywine River Museum, Reflections of American History, June-September 1976, n.n.

Douglas Allen and Douglas Allen, Jr., N.C. Wyeth: The Collected Paintings, Illustrations and Murals, New York, 1972, pp. 142, 287, illustrated

Christine B. Podmaniczky, N.C. Wyeth: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, vol. II, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, 2008, no. C-51, p. 654, illustrated

On the eve of the American Revolution in April 1775, the colonial governments of Massachusetts had been dissolved and their members had gone into hiding in the towns of Lexington and Concord. On April 18, Joseph Warren, a member of the Sons of Liberty, discovered that the British planned to march on the towns that night. He dispatched two messengers, the silversmith Paul Revere and tanner William Dawes, to carry the news. Immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1860 poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Revere hung two lanterns in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church, the highest point in the city, to alert the Patriots of the Redcoats’ imminent arrival by sea.

At dawn on April 19, around 700 British soldiers marched west to Lexington to confiscate American weapons and supplies (which had already been evacuated), a mission they began by establishing a presence along the bridges around the towns. When the locals got wind of their plan, a small group of militiamen gathered their weapons, marched to Lexington, and prepared to fight. Shots were briefly exchanged, and to this day it is unknown which side fired first. Eight militiamen were killed and nine wounded, but only one Redcoat was injured. In Concord, however, the British encountered a greater resistance.

As the British entered Concord in search of more arms to remove, about 400 American militiamen appeared and marched towards them. After quickly torching what they could, the British retreated to the east side of Concord's North Bridge, while the militiamen took up position on the west side, hundreds more arriving by the minute. Shots were fired, and the British were forced to retreat, abandoning weapons and equipment as they fled. When they reached Lexington, they met up with another brigade of Redcoats who had answered their calls for reinforcements, but the militiamen, as many as 3,500 by the end of the day, continued their pursuit all the way to Charlestown Neck, where the British found naval support.

While the fighting technically began at Lexington, Concord is considered the first battle of the American Revolution, as it was the first time that the militia was formally ordered to fire upon British soldiers. This was considered treason against the British Empire and gave rise to Ralph Waldo Emerson's famous phrase, "the shot heard round the world." The Battles of Lexington and Concord, with their relatively low American casualties (only about 90, versus the Redcoats’ 250), was a significant victory for the revolutionaries’ morale, for it proved that their militias could stand up to the military might of the British forces.

While Longfellow and Emerson’s writings are not completely accurate, they are historically significant, for they cast the events of Lexington and Concord as one of the first American adventure stories. When he completed Independence Day, N.C. Wyeth had been illustrating works of classic American literature for close to a decade, his work for novels such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans having made him a household name. Wyeth’s book illustrations have since come to define the way many famous tales and characters look in the American imagination, yet he was always conscious of falling victim to the traditional distinction between illustrator and artist, his ambition to be regarded as one of the great American painters tempered by pressure to support his large family with literary and commercial work.

Wyeth found a compromise in commissions in which he could interpret stories that are more than works of fiction: those works which evoke key moments in the nation’s history have helped to solidify his legacy as one of America’s best-loved artists, for they bring together his unparalleled eye for storytelling and his determination to become part of the American narrative. It is thus no wonder that the thrilling story that began the American Revolution appealed to Wyeth, who in fact painted the scene at Concord Bridge twice. The present work was painted in 1921 for use as a bank holiday poster, published by Canterbury Company, Chicago. Canterbury's owner, advertising executive Charles Daniel Frey, retained the painting and it descended in his family until 1969.

S. Hallock du Pont, Jr., an avid collector of American illustration and African wildlife art, acquired Independence Day in 1973. The world of illustration captured Mr. du Pont's imagination and spirit of adventure, and paintings by N.C. Wyeth in particular held a connection to the du Pont family's roots in the Brandywine River Valley. Growing up in Wilmington, Delaware, Mr. du Pont spent much of his youth exploring the wetlands of the River, and from age seven, his passion for wildlife and landscape photography developed his keen eye for the beauty of exploration. Mr. du Pont saw that same spirit in Independence Day, recognizing N.C. Wyeth’s distinct ability to sweep the viewer away from the everyday, into their imagination, and onto an adventure.

You May Also Like