PROPERTY FROM AN EUROPEAN COLLECTION

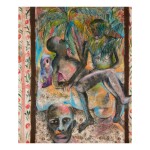

BHUPEN KHAKHAR | IN THE COCONUT GROVES

Auction Closed

March 16, 05:19 PM GMT

Estimate

200,000 - 300,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

PROPERTY FROM AN EUROPEAN COLLECTION

BHUPEN KHAKHAR

1934 - 2003

IN THE COCONUT GROVES

Oil on printed cloth with a cushion backing laid on board

Signed and dated in Gujarati lower right

Bearing a TATE exhibition label on reverse along with another label with cataloguing details and exhibition history in India from the 1990s

66 x 55 ⅛ in. (167.6 x 140 cm.)

Painted in 1993

Christie's London, 16 October 1995, lot 78

New Delhi, Vadehra Art Gallery, Reflection & Images, 1993

Mumbai, Jehangir Art Gallery, Reflection & Images, 1993

London, Tate Modern, Bhupen Khakhar: You Can't Please All, 1 June - 6 November 2016

Berlin, Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Bhupen Khakhar - You Can't Please All, 18 November 2016 – 5 March 2017

C. Dercon and N. Raza, Bhupen Khakhar: You Can't Please All, Tate Publishing, London, 2016, illustration p. 66

Renowned as India’s first Pop artist, Bhupen Khakhar painted the people and places from his environment with colorful wit and humor throughout his career. Khakhar was raised in Bombay, where he earned a degree in accounting before the artist Gulammohammed Sheikh encouraged him to shift to the university town of Baroda to study art criticism in the early 1960s. Khakhar then worked in Baroda simultaneously as a chartered accountant, writer in Gujarati, and practicing artist for the rest of his life. In doing so, he mediated the cosmopolitan art world in Bombay and the academic intellectual art community in Baroda, as well as the middle-class life and society that his accountancy offered; this matched the multiple dimensions and identities of his life as they unfolded in coming decades.

Khakhar first developed his artistic practice among a group of artists and intellectuals emerging in the mid-1960s. While remaining centered on the figure, this generation challenged the metaphysical concerns of Indian art that prevailed in the immediate post-independence period. Through their focus on narrative, Khakhar, Sheikh, Vivan Sundaram, and their peers represented the milieu and concerns of daily life in urban India. Khakhar was largely self-taught and developed a consciously naive style, wryly remarking on occasion that he was a “Sunday painter.” This was even as his work made sophisticated reference to diverse popular and art historical sources, ranging from fourteenth century Siennese painting to Indian miniatures, as well as sometimes misunderstood or veiled engagements with contemporary developments in Euro-American modernism, particularly Andy Warhol’s Pop. Through the British painter Howard Hodgkin and then Timothy Hyman, RB Kitaj, and others, Khakhar traveled abroad and began to achieve mainstream international acclaim in the late 1970s.

While Khakhar’s art was often autobiographical or self-reflective from the onset of his career, his public coming out in 1981 through the painting You Can’t Please All marked a critical and decisive shift. Significantly, Khakhar included this work in the seminal 1981 exhibition “Place for People,” which asserted strongly a focus on narrative compositions drawn from local or personal experience. Following this time, much of the artist’s work considered his own homosexuality and depicted erotic encounters, a particularly courageous gesture at a time when homosexuality was still largely unseen in the Indian public sphere. In this decade, the compositions of Khakhar’s canvases became increasingly complex and layered, with an increased focus on visual and narrative depth.

By the 1990s, Khakhar was recognized in India and abroad for pioneering tender and funny portrayals of life as he encountered it, especially but not only through a continued exploration of homoerotic themes. Early in this decade he suffered from cataracts, loosening his brushwork and lending to compositions focused on central figures for several years. The present painting is a distinctive example of these developments and centers on an amorous encounter between two men in a lush tropical environment, while a third face (with a resemblance to Khakhar) at the bottom of the plane looks at the viewer. However, Khakhar “frames” the central narrative by painting brown vertical borders around the painting, adding a painted floral “wallpaper” to both the left plane and right edge. The illusionism of this device is cleverly and cannily interrupted by one of the men’s legs extending over the frame, with his toes then cut off by the real border of the painting. Different expressions of this strategy can be seen in major works of the mid 1990s, such as Green Landscape (1995), in which a picturesque landscape painting is surrounded by an extended border showing a panoply of male figures, both individuals and couples (with one figure seeming to sit atop the landscape, breaking that frame). Through this approach to composition, Khakhar continues his career-long subversion of any tendency to read his work as serious or simply at face value. At the same time, both the style and immediacy of the subjects depicted create a feeling of intimacy and honesty that challenges even his cheeky wit. In virtually breaking the frame of the work, Khakhar thus presents a reflection on the language and limitations of painting itself, in dialogue with an ongoing questioning of a place for painting in contemporary India.