Property of another Owner

John Hancock, manuscript letter signed, announcing the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, 6 July 1776

Auction Closed

January 27, 09:56 PM GMT

Estimate

600,000 - 800,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property of another Owner

HANCOCK, JOHN

MANUSCRIPT LETTER SIGNED AS PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS (“JOHN HANCOCK PRESIDT”), ANNOUNCING THE ADOPTION OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

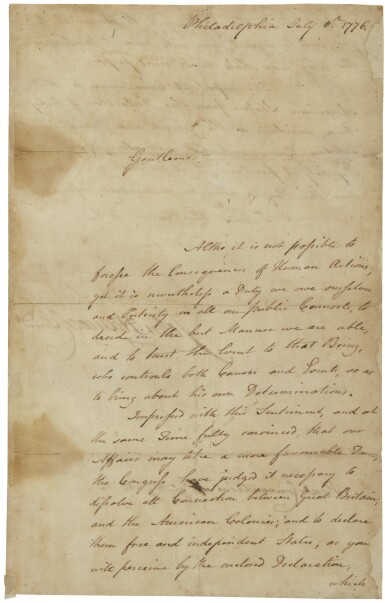

2 pages (12 ⅝ x 8 in.; 322 x 204 mm) on the first leaf of a bifolium, body of the letter in a secretarial hand (likely Jacob Rust), Philadelphia, 6 July 1776, salutation reads "Gentlemen,” and address direction at end of reads “Honl. Convention of [obscured]”; silked, stained, abraded in spots, some fold separations and marginal chips, separated from integral blank at central fold.

President of Congress John Hancock announces the adoption of the Declaration of Independence: “the Congress have judged it necessary to dissolve all Connection between Great Britain, and the American Colonies; and to declare them free and independent States. …”

The text of the Declaration of Independence—which announced and justified America’s resolution of separation from Great Britain—was first printed on the evening of 4 July 1776, by John Dunlap. But when the Continental Congress convened for session in May of that year, the issuance of such a declaration was far from a foregone conclusion. A coalition of delegates from Mid-Atlantic states, led by Pennsylvania's John Dickinson, advocated a cautious approach towards independence and may even have harbored hopes for an equitable reconciliation with Britain.

The first step towards the Declaration was Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee’s resolution of 7 June, “that these United Colonies are, and of right, ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” This provoked sharp debate in the chamber, with South Carolinian Edward Rutledge confiding to John Jay that “The Sensible part of the House opposed the Motion. ... They saw no Wisdom in a Declaration of Independence nor any other Purpose to be answer’d by it, but placing ourselves in the Power of those with whom we mean to treat. ...” But firebrands like John Adams carried the day and on 11 June 1776 the Continental Congress appointed a committee of five members to draft a declaration endorsing Lee's resolution. Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Robert R. Livingston of New York formed the committee.

Jefferson was chosen to write the Declaration, in recognition of his (in John Adams's words) “peculiar felicity of expression.” His extensively reworked Rough Draft, as it is commonly known, is preserved in the Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. In addition to Lee’s resolution, Jefferson drew heavily on two other fundamental sources for his text: George Mason’s bill of rights, adopted by Virginia on 12 June 1776, and his own draft of a proposed constitution for Virginia. Jefferson felt great satisfaction for the rest of his life in having been privileged to serve as chief author of this greatest of American documents. Shortly before his death, Jefferson wrote to Richard Henry Lee, responding to the remarks of John Adams and others that the Declaration only stated what everyone at the time believed. He had been concerned, he wrote, “not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent ... it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.”

As is evident from their annotations on the Rough Draft, Adams and Franklin read and commented on Jefferson's version, making relatively small changes. There is no direct evidence of revision from the hands of Sherman and Livingston. A fair copy (now lost), incorporating these changes, was submitted to the full body of the Continental Congress, which debated it for three days before approving it on 4 July 1776.

The most substantial modification made in Congressional discussion was that the final point of Jefferson's charge against the British king, that of “violating [the] most sacred rights of life & liberty” by encouraging the slave trade, was struck out. Jefferson's own notes made at the time of the debates state that this was done “in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it.” With that major change, Congress adopted the Declaration and authorized its printing, resolving “That the committee appointed to prepare the declaration superintend & correct the press; That copies of the declaration be sent to the several Assemblies, Conventions & Committees or Councils of Safety and to the several Commanding Officers of the Continental troops that it be proclaimed in each of the United States & at the head of the army.” No roll call was recorded, but the vote to adopt and issue the Declaration was unanimous by colony, although apparently there were dissenting votes in both the Pennsylvania and Delaware delegations and New York abstained completely.

That same evening, a manuscript copy of the Declaration, evidently bearing the authorizing signature of John Hancock, was taken to the shop of John Dunlap, official printer to Congress, which was located within walking distance of the Statehouse at 48 High Street and Market Street. Dunlap evidently spent the evening of 4 July 1776 setting the Declaration in type. At least one proof was taken, a fragment of which survives at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at Philadelphia. It chiefly varies from the finished copies in putting many phrases within quotation marks which were afterward removed, in some cases leaving unusually large gaps between words. Finished copies were pulled and delivered to Congress the morning of 5 July; the number of copies printed is unknown, but it is likely that the Dunlap broadside was printed in substantial numbers, perhaps between 500 and 1,000 copies.

Among the very first copies of the Declaration to be distributed were those ordered by Congress to be “sent to the several Assemblies, Conventions & Committees or Councils of Safety and to the several Commanding Officers of the Continental troops.” One of those printings of Dunlap’s broadside would have been accompanied by the present extraordinary letter, signed by John Hancock as President of Congress, 6 July 1776, and dispatched to one of the original thirteen states:

“Altho it is not possible to foresee the Consequence of Human Actions, yet it is nevertheless a Duty we owe ourselves and Posterity in all our public Counsels, to decide in the best Manner we are able, and to trust the result to that Being, who controuls both Causes and Events, so as to bring about his own Determinations.

“Impressed with this Sentiment, and at the same time fully convinced, that our Affairs may take a more favourable Turn, the Congress have judged it necessary to dissolve all Connection between Great Britain, and the American Colonies; and to declare them free and independent States, as you will perceive by the enclosed Declaration, which I am directed by Congress to transmit to you, and to request you will have it proclaimed in the Way you shall think most proper.

“The important Consequences to the American States from this Declaration of Independence, considered as the Ground and Foundation of a future Government, will naturally suggest the Propriety of proclaiming it in such a Manner that People may be universally informed of it.”

Hancock evidently wrote thirteen near-identical letters between 5 and 8 July, one for each of the colonies (he also wrote similar letters to generals George Washington and Artemas Ward). Nine versions of Hancock’s letter-announcement to the colonies of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence—each supplemented by a copy of John Dunlap’s broadside printing of the Declaration—can be accounted for, as follows.

¶ New Jersey: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Honble Convention of New Jersey,” 5 July 1776. (This letter appeared in the Rosenbach Company’s Catalogue 14 [1949], item 34. and was exhibited at that time at the University of California, Los Angeles. It had earlier been in the collections of Abraham Tomlinson and the Mercantile Library Association of the City of New-York and bears ink stamps from these two owners. The letter was evidently sold by Rosenbach, or by his successor, John Fleming, to Raymond E. Hartz. It was subsequently acquired, about 1991, by the Gilder Lehrman Collection, and is now housed at the New-York Historical Society.)

¶ Delaware: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Col. [John] Haslet, or Officer commanding the Battalion of Continental Troops in Delaware Government,” 5 July 1776. (The current location of this letter, if it survives, has not been traced.)

¶ Pennsylvania: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Honourable Committee of Safety of Pennsylvania,” 5 July 1776. (This letter is now in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

¶ Massachusetts: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Honble Assembly of Masstts. Bay,” 6 July 1776. (This letter is known to have been sent by the retained letterbook of the Continental Congress, but its current location, if it survives, has not been traced.)

¶ New York: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Honble Convention of New York,” 6 July 1776. (This letter is known to have been sent by the retained letterbook of the Continental Congress, but its current location, if it survives, has not been traced.)

¶ Connecticut: Hancock sent a letter addressed to Governor Jonathan Trumbull, 6 July 1776. (This letter is known to have been sent by the retained letterbook of the Continental Congress, but its current location, if it survives, has not been traced.)

¶ Rhode Island: Hancock sent a letter addressed to “Honble Govnr [Nicholas] Cooke,” 6 July 1776. (This letter is now in the collection of the Lilly Library, Indiana University.)

¶ New Hampshire: Hancock sent a letter addressed to “Honble Convention Assembly of New Hampshire,” 6 July 1776. (This letter was purchased by the Rosenbach Company from the rare book firm Dodd & Livingston prior to 1912. It was featured in several Rosenbach catalogues from Catalogue 6 [1911], item 258, to Catalogue 64 [1937], item 28. The letter was evidently sold by Rosenbach, or by his successor, John Fleming, to Philip D. Sang, who placed it on deposit at Rutgers University. The letter was subsequently obtained by another collector who consigned it to auction at Sotheby’s New York, 23 May 1984, lot 157. The letter is currently privately owned.

¶ Maryland: Hancock sent a letter addressed to the “Honble Convention of Mary Land,” 8 July 1776. (Although Letters of Delegates to Congress 1774–1789, ed. Smith, 4:396, locates this letter in the Purviance Papers at the Maryland Historical Society, the Historical Society in fact has only a contemporary clerical copy of the letter. The current location of the original signed letter, if it survives, has not been traced.)

The direction, or address line of the present letter is abraded, but by process ofelimination it can be determined that it must originally have been intended for Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, or Virginia. However, just because the letter might have originally been sent to Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, or Virginia does not mean that state would have retained it. Record keeping was chaotic and archives an afterthought in many of the colonies during the foment of revolution. It is likely that once Hancock’s instruction that the Declaration be “proclaimed” was fulfilled, both his letter and the Declaration broadside that accompanied it were taken home as souvenirs by members of the crowd gathered for the reading. It is worth noting that less than half (5 of 13) of the Hancock Declaration cover letters have survived—none of which is in its respective state archive, and only one of which is even currently located in the state to which it was originally sent.

As for the postcolonial provenance of the present Hancock letter, the earliest reference to it that Sotheby’s can find is its inclusion in the auction catalogue of the Collection of Autographs of Col. Thomas Donaldson, lot 198, sold in Philadelphia by Stan Henkels, 26 October 1899. The letter is illustrated, and there is no doubt that it is the same manuscript. A copy of the Donaldson catalogue with buyers’ names noted in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania identifies the purchaser of lot 198 as “Howard.” The most likely buyer would be Arthur P. Howard, who had a sale at American Art Association, March 6, 1925, titled “Books and Autographs (Revolutionary War)”—but the Hancock letter was not in the catalogue (of course it could have been sold either before or after the single-owner auction). At some point in the 1920s or 1930s, the letter was part of the private collection of Harry F. Marks, a prominent New York books and manuscripts dealer, ca. 1910–1950. (Marks may well have obtained the letter from Arthur Howard.) Among other evidences of Marks’s ownership is the December 1937 issue of a hobby magazine titled Avocations, which, in a brief profile of Marks, states that his private collection included “a signed copy of the letter which accompanied the original transcripts of the Declaration of Independence.”

Hancock’s letter eloquently conveys the gravity of the steps Congress had taken by severing ties with Great Britain, and “The important Consequences to the American States from this Declaration of Independence” that he foresaw redound to the present day. As a primary witness to the American Revolution; as an epitome of the Declaration of Independence; and as a statement of principle by one of the fifty-six Signers who pledged to each other their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor, this John Hancock letter and its few surviving companions stand sole and incomparable.