THE PROPERTY OF AN ENGLISH GENTLEMAN

A FINE AND RARE LACQUER MODEL OF AN ELEPHANT, SIGNED MUCHU-AN HARITSU, SEALED KAN. EDO PERIOD, 18TH CENTURY

Auction Closed

November 3, 04:10 PM GMT

Estimate

70,000 - 90,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

THE PROPERTY OF AN ENGLISH GENTLEMAN

A FINE AND RARE LACQUER MODEL OF AN ELEPHANT

SIGNED MUCHU-AN HARITSU, SEALED KAN

EDO PERIOD, 18TH CENTURY

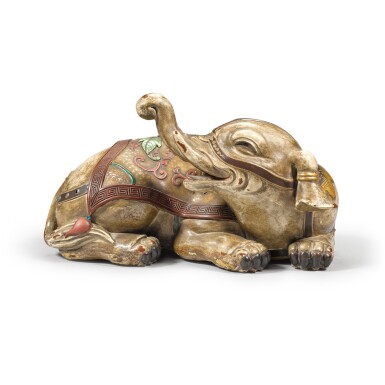

the recumbent elephant, its head turned to the right and its trunk raised, wearing an elaborate harness and saddle-cloth decorated in low relief with a large peony in bloom, the details inlaid in silver, gold, tsuishu, blue and green-glazed pottery, hardstones, mother-of-pearl and stag antler, its eyes inlaid in glass with black pupils, signed Muchu-an Haritsu with seal Kan

25 cm, 9 7/8 in. long

This okimono, a small decorative carving of a highly ornate elephant and trappings, is an extremely rare example of a work by Ogawa Haritsu (1663-1747), also commonly known in the West by one of his art names, Ritsuo. Although born in Ise, he worked most of his life in the capital Edo. Apart from being employed by the daimyo of Tsugaru from around 1720-34, he was an independent artist for most of his life, displaying enormous originality and technical prowess. Haritsu was a man of many talents and skills, producing much innovative work, such as successfully simulating other materials in the lacquer medium, something taken up later by the talented Shibata Zeshin (1807-91). Apart from being an extremely accomplished lacquerer, Haritsu also studied painting in the Tosa style, probably with Hanabusa Itchō (1652-1724), Haiku poetry with Matsuo Bashō (1644-94) and ceramics with Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743).

Haritsu is most widely known for his work in lacquer, particularly producing suzuribako (writing boxes), netsuke and inro (tiered, decorative carrying containers). Not only is the form of the elephant as an okimono extremely unusual, but it is also made of glazed pottery, something that Haritsu was more than capable of producing himself. Much of his lacquerwork not only includes ceramic inlays as part of the decoration, but also as part of his seal.[1] The most striking and characteristic feature of Haritsu’s lacquerwork, however, is the inlay of a wide variety of materials, such as pearl-shell, ivory, hardstones, metal and carved lacquer into a ground of specially selected rough wood or lacquer; this type of work is termed Haritsu-zaiku (Haritsu’s inlaid lacquer). Although such virtuosity owed much to the native Rinpa tradition using limited inlaid materials, it was undoubtedly the influence of inlaid Chinese arts and crafts of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) periods that particularly influenced Haritsu.

The frequent use of an elephant as the main subject of many works by Haritsu cannot be overlooked.[2] Although the elephant was not native to Japan, it was nevertheless known from an early date through paintings and sculptures as part of Buddhist iconography. The first living elephant to reach Japan was brought by Koreans in 1408, and again in 1597 and 1724 by Europeans. This last occasion was well documented and included the symbolic gift of a white elephant from the king of Siam to the Japanese emperor Nakamikado (r. 1710-35). This event, as well as the supply of another animal by the Dutch in 1813, not only made a lasting impression on the Japanese, but also did much to raise the profile of the elephant in public consciousness, resulting in an outpouring of paintings, woodblock prints and book illustrations on the subject. Although it would be nice to believe that Haritsu caught sight of the elephant in 1724, this seems highly unlikely. Instead the source of Haritsu’s elephants was undoubtedly the Chinese book Fang shi mopu (Mr. Fang’s ink-cake manual) illustrated by Fang Yulu (fl. 1570-1619) and published around 1588.[3] This illustration depicts a richly caparisoned elephant with an ornate howdah on its back. The fact that this was printed in black and white gave the artist a free hand in selecting the colours, materials and details for the design. The main difference between the okimono and the original illustration is that the okimono elephant is recumbent with its head raised and trunk extended rather than standing still. In addition the howdah has been omitted by Haritsu, probably for reasons of size and space, and was replaced by a prominent flowering peony, giving even greater scope to Haritsu’s expression in lacquer.

A signature is cleverly contained within the elaborate strapping of the ornate saddlecloth on the underside of the okimono. It reads ‘Muchūan Haritsu’ with the seal ‘Kan’, Muchūan (lit. hut of dreams) was Haritsu’s studio-name which derives from Zhuangzi, his favourite Chinese Taoist work. It is interesting that although ‘Kan’ is normally inlaid in green-glazed pottery, in this instance it is carried out in raised red lacquer. This is undoubtedly because the body is already made of pottery and a greater contrast could be achieved by using lacquer instead.

[1] Okada Jō, Nihon no shitsugei, vol. 5, pls 121-123 and Joe Earle (ed.), The Toshiba Gallery:Japanese Art and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986 (first published), pl. 37, V&A inventory nos. W.56/ 57-1922.

[2] Some of the most well-known examples can be found in Akio Haino, Ritsuō zaiku (Inlaid lacquerwork by Ritsuō) [ex. Cat.], Kyoto National Museum, 1991, cat. 10, 11, 12 and 13.

[3] Little, Stephen and Edmund J. Lewis, with contributions by John Stevens, View of the Pinnacle:Japanese Lacquer Writing Boxes, The Lewis Collection of Suzuribako, Fig. 1, p.120.

For a similarly conceived and lacquered netsuke of a recumbent elephant, sold at Sotheby's London, 20th February 1986, lot 108. Compare also with the eclectic combination of styles and media used in the decoration of a sumptuously-caparisoned standing elephant ornamenting a suzuribako by the artist, in the Hikone Castle Museum, illustrated, Nihon no Bijutsu 10, no.389, p.1 and discussed inter alia, ibid., pp.17-80 by Haino Akio. Compare also with another example in the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, illustrated, ibid., p.5, illus. pl.9.