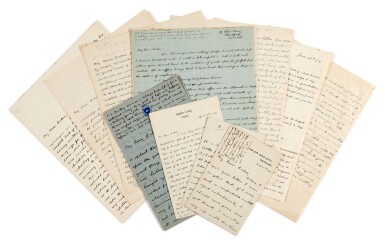

LEWIS, C.S. | Series of 10 autograph letters signed, to Leo Baker, 1920-36

Lot Closed

December 8, 04:54 PM GMT

Estimate

7,000 - 9,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

LEWIS, C.S.

Series of ten autograph letters signed ("Clive Lewis", "C.S. Lewis"), to Leo Baker

a thoughtful correspondence to a close friend discussing poetry, religion, pain, and other subjects, 42 pages, various sizes, Belfast, Magdalen College Oxford, the Oxford Union Society, and Washford in Somerset, 12 January 1920 to 24 June 1936

[with:] Photographic portrait of the young Lewis, full-length in the countryside round Oxford in the early 1920s, vintage copyprint

[also with:] Leo Baker, typescript memoir on his relationship with Lewis entitled 'Near the Beginning', 9 pages, and correspondence relating to it and its publication in C.S. Lewis at the Breakfast Table, 1970s

A DEEPLY REVEALING AND INTENSE CORRESPONDENCE BY THE YOUNG C. S. LEWIS. Leo Baker befriended Lewis in October 1919 when they were undergraduates at Oxford. Both men had served as officers in the trenches of World War I before returning to academic study, and both had poetic ambitions. They were introduced by a mutual friend, Rodney Pasley, and the three men were soon part of a small group of students who encouraged each other's poetic ambitions. As early as January 1920, Lewis writes with great frankness to Baker about his dislike of his family home in Belfast ("...a synonym for busy triviality, continued interruption and a complete lack of privacy..."), whilst worrying that Baker's threatened departure from Oxford would upset the delicate balance of their small poetic coterie ("...Pasley will tend gradually to modernism, I to medievalism...").

Poetry is the over-riding subject of Lewis's early letters to Baker, whether he be comparing Spenser with Milton ("...To see Milton's real greatness one need but notice the fresh joy and reality of his Eden after the over-ripe stanzas which describe the garden of Acrasia...."), attempting a definition of poetry, or sending Baker some of his own verses for comment (13 lines, commencing "Oh that a black ship now were bearing me...") They were hoping to publish a small anthology of their own poetry. Lewis was tasked with writing a preface, which elicited a significant bout of self-doubt from the future Professor in the Cambridge English faculty: "I am become more and more convinced of the futility of any theorizing about poetry. It is not by our theories that we shall stand or fall". In the end, however, it was more mundane concerns that thwarted publication: "The blow has fallen Basil [Blackwell] refuses to publish the dam' thing unless we raise some money."

Religion and belief is another recurring theme in these letters. In the early 1920s Lewis was a resolute atheist, but there are glimpses in the letters of his changing attitude: "You will be interested to hear that in the course of my philosophy - on the existence of matter - I have had to postulate some sort of God as the least objectionable theory: but of course we know nothing." Baker's own struggles with religious belief are also a theme of the letters, and in one letter, fresh from a book that Baker had sent him, Lewis discusses how difficult he finds Buddhism's rejection of the idea of selfhood.

At some point in the 1920s the two men argued and broke off relations - although there are no surviving letters relating to the breach. Lewis wrote to Baker on 28 April 1935 to renew their friendship, having heard that Baker was suffering from serious health problems. He sums up his own life pithily:

"My father is dead and my brother has retired from the army and now lives with us. I have deep regrests about all my relations with my father (but thank God they were best at the end). I am going bald. I am a Christian. Professionally I am chiefly a medievalist. I think that is all my news up to date."

He admits that "I hardly write anything these days except things proper to a don". Poetry remains a subject in these later letters, and Lewis admits that his chief love is now "old germanic poetry, which, as a friend says, sometimes makes everything else seem a little thin or half-hearted". This anonymous friend is likely to have been J.R.R. Tolkien. Lewis's own career was at a crucial stage in the mid-30s and he recounts an exchange with a senior professor in Oxford who tells him that he "gone beyond the whole English school with your new book", only to discover that what he means is that The Allegory of Love is "Much the longest book any of us has written" (24 June 1936). These letters also contain powerful words of sympathy for a friend whose life is circumscribed by chronic pain:

"I am told that the great thing is to surrender to physical pain - I mean not to do what's commonly called 'standing' it, above all not to brace the soul (whcih usually braces the muscles as well) not to try to ignore it: to be like earth being ploughed not like marble being cut."