THE SHAKERINE COLLECTION: Calligraphy in Qur’ans and other Manuscripts

THE SHAKERINE COLLECTION: Calligraphy in Qur’ans and other Manuscripts

A MONUMENTAL QUR’AN PAGE AFTER THE 'BAYSUNGHUR' QUR’AN, PERSIA, QAJAR, 20TH CENTURY

Auction Closed

October 23, 11:03 AM GMT

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

A MONUMENTAL QUR’AN PAGE AFTER THE 'BAYSUNGHUR' QUR’AN, PERSIA, QAJAR, 20TH CENTURY

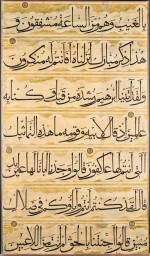

Arabic manuscript on paper, 7 lines to the page written in monumental muhaqqaq in black ink within clouds against a gold ground, verses marked by gold roundels, in plexiglass frame

170.5 by 99cm.

Bonhams London, 1 May 2003, lot 56.

N.Safwat, A Collector's Eye. Islamic Calligraphy in Qur'ans and Other Manuscripts, London, 2010, pp.296-7.

The present page is a late nineteenth/early twentieth century copy of a monumental page from the famous 'Baysunghur' Qur’an. The original Timurid pages were so praised and admired in the Qajar period that were copied as a testament to one of the most important Qur’anic productions of all time.

The original so-called 'Baysunghur' Qur’an was produced in the beginning of fifteenth century. The association with Baysunghur dates to the early nineteenth century when the collector of Oriental manuscripts James Baillie Fraser, saw a section of this Qur'an in Quchan, in north-east Iran. Although Baysunghur was a competent calligrapher, there is no historical evidence that he undertook so arduous a task as copying a Qur'an of this size since it would have taken between six and eight months to complete the work on the assumption that he was able to find the time to copy ten pages a day. The undertaking would certainly not have gone unnoticed by his contemporaries and would have been recorded in the chronicles of the time. James concludes that the attribution was probably based on circumstantial evidence since at one stage the manuscript was kept in the mausoleum of his grandfather, Timur in Samarqand (James 1992, pp.18-25). The manuscript remained there until the city was captured by Nadir Shah in the eighteenth century. The Shah's troops dismembered the manuscript and stole many of its leaves, which were later lost or badly damaged. Some of the remaining pages were placed in the imamzadah of Shahzadah Ibrahim ibn ‘Ali b. Musa al-Rida in Quchan until 1912 when Prince Muhammad Hashim Afshar brought them to Mashhad.

The attention and reverence accorded during the Qajar dynasty to the original Timurid manuscript is an important historical point as it contextualises the current page. Many of the original Timurid pages were dispersed or damaged during the nineteenth century and many heavily restored. As a result of their dispersion in more than one site in Persia (including Quchan and Mashhad), a desire to have similar exercises of monumental calligraphy started to take hold in the end of the century, leading to the production of pages imitating the original Timurid version.

The current page is stylistically and structurally very similar to a page now in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection (inv.no.QUR.596, published in James 1192, pp.24-25). While the Timurid original pages were composed of a single sheet of paper, a major challenge to produce, and had a density of four to five laid lines to the centimetre, the reproduction copies are composed of more than one piece of paper with denser concentration of laid lines (around eleven laid lines to the centimetre). The current page has been laid down on several layers of paper and card, so it is not possible to identify the number of laid lines by centimetre, but it is also composite, as with the Khalili example.

Both leaves have very close dimensions (the Khalili page measures 168 by 97.5cm. and the interlinear spacing is 24cm); the verse markers are nearly identical, the diacritical markers in both have rhomboid and circular shapes and the length of the ‘alif varies between thirteen and fourteen centimetres. The main difference between the two examples is the ground: the Khalili page has been left plain, while the present example has the addition of old illumination.