Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art

Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art

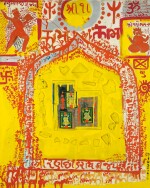

BHUPEN KHAKHAR | Interior of a Hindu House - I

Auction Closed

June 10, 02:40 PM GMT

Estimate

90,000 - 120,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

BHUPEN KHAKHAR

1934 - 2003

Interior of a Hindu House - I

Oil, mirror, collage and mixed media on canvas

Signed and dated 'Bhupen Khakhar '65' lower right and further titled and inscribed 'INTERIOR OF / A HINDU HOUSE / - I / Rs 250/-' on reverse

76.5 x 61.4 cm. (30 ⅛ x 24 in.)

Painted in 1965

Acquired by the artist Roy Dalgarno, circa 1960s, India

Cordy's Auckland, 6 October 2015, lot 702

Private Collection, New Zealand

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2016

In the 1950s, Australian artist Roy Dalgarno moved to India where he befriended Bhupen Khakhar, as well as artists such as Himmat Shah, Vivan Sundaram, and Gulammohammed Sheikh. In India, Dalgarno first became director of an advertising agency in Bombay, subsequently teaching lithography and setting up a printmaking studio in Baroda at M.S. University. Dalgarno was best known for the Studio of Realist Art (SORA; founded in 1946) and the social realist works that he created.

Born in Mumbai into a middle-class Gujarati family, Bhupen Khakhar first trained as an accountant. In 1962, he moved to Baroda and chose a new career as a writer and an artist. At first self-taught, Khakhar was encouraged by his friend Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and later became a key figure at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Baroda.

Although one would imagine Khakhar to have been influenced by the Progressives during his time as a student at the J. J. School of Art in Mumbai (then Bombay), he is said to have found the school uninspiring and dull. Writing about Khakhar’s time at J. J., as the school is affectionately called, Timothy Hyman states that the artist felt it offered ‘absolutely no teaching’ and ‘hardly any direction’. (T. Hyman, ‘Training in Baroda’, Bhupen Khakhar, Chemould Publications and Arts, Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, 1998, p. 9) Khakhar recollects that the school's renowned professor, Shankhar Palsikar "never came to instruct me, even once in six months… I was very cheesed off.” (B. Khakhar quoted in ibid) By contrast, the Faculty of Fine Arts at Baroda where he took the Art Criticism course was a breath of fresh air for Khakhar – it was new, it was contemporary. It was in this atmosphere of free thought that Khakhar thrived.

When he moved to Baroda in the early 1960s, Khakhar shared a flat for a short while with fellow student Jim Donovan in the city's Old Town. With his British roots, Donovan was instrumental in introducing Khakhar to the Pop art movement in Britain at the time led by Richard Hamilton, and it was this encounter that formed the central core of Khakhar’s philosophy. (Hyman, ibid, p. 12-13) Collages were among the first works of art Khakhar produced. Like many of his contemporaries, Khakhar broke with convention in favour of this radical art form, juxtaposing found objects as a form of artistic expression. With regards to this choice of medium, it is also important to note that at this point he had not fully trained as a painter. It would be a few years before Khakhar would make his debut as a painter with People in Dharamshala which he painted in 1968. (T. Hyman, ibid. p. 15) Collages, despite their early significance to the artist, remain Khakhar's rarest art form.

An early proponent of the 'Pop' era in India, Khakhar’s earliest works such as Interior of a Hindu House – I, painted just three years after he began his artistic journey, embody that impulse of a young, independent mind, eager to peel off all that was conventional and established, and re-examine it on his own terms. Here, Khakhar takes on this challenge with a bravura and an unrivalled spirit of experimentation. By integrating found objects like bits of discarded plastic, mirrors and photos of Shrinathji, an avatar of the Hindu God Krishna, Khakhar elevates them to the equivalent of fine art. Such decorated archways and niches, replete with idols and photos, become mini temples within people’s homes, a place to worship without ever leaving the abode. It is extremely commonplace to have these capsule shrines in Hindu houses, so by recreating this imagery on a canvas, which was considered the most prestigious and expensive medium for artists in the 60s, he is recapturing the Duchampian spirit of elevating the everyday and celebrating the ordinary. Later on, in Khakhar's mature painting phase as seen in Two Men in Benaras, Khakhar continues with his convention of dividing his canvases into narrative vignettes and employs the varying shades of blues and indigos which hearken back to his earlier Shrinathji and Pichvai influences.

Interior of a Hindu House – I reflects the beauty and vitality of the colours Khakhar observed in the bustling bazaars, narrow crowded streets and the numerous shrines and temples that surrounded him in Baroda. Like most Baroda School artists, Khakhar’s work was about the narrative. The imagery created using cheap found objects and man-made materials set against organic shades of turmeric yellow and chilli red is one of contrast and contradiction; a utopian vision of an industrialised modern India at odds with her ancient traditions which he alludes to through religious symbolism and fragments cut from print media, each on the fringes of art yet expertly brought together in a cohesive composition.

‘When [these] images were shown in 1965, they presented an ambivalent meaning. Mirrors were patterned with little divinities, cut from the lurid oleograph-prints sold in the temple-bazaars, and then buoyed up with graffiti and gestural brushwork. Sometimes we see a simplified face (two black spots and an upturned crescent) recalling the primitive pats of Shri Jagannath at Puri. […] Was Khakhar sneering at, or celebrating, the imagery of popular religion? When Vivan Sundaram tried an experiment – hanging one of the collages in the Fine Arts canteen – he found it a few hours later, torn to shreds. The illiterate canteen workers were in no doubt; it was blasphemy. In the Indian context, these images were striking, surprising and original, the explosion of a new talent. Exhibited at Gallery Chemould, in the centre of Bombay (at the time one of only four contemporary art dealers in India), they sold well, and gained him instant recognition as “India’s first Pop artist.”’ (T. Hyman, Bhupen Khakhar, Chemould Publications and Arts, Bombay and Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, 1998, pp. 14-15)