Property from the Private Collection of Jean and George S. Rosenthal

HARRY BERTOIA | UNTITLED (WIRE CONSTRUCTION)

Auction Closed

December 12, 09:10 PM GMT

Estimate

150,000 - 200,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Private Collection of Jean and George S. Rosenthal

HARRY BERTOIA

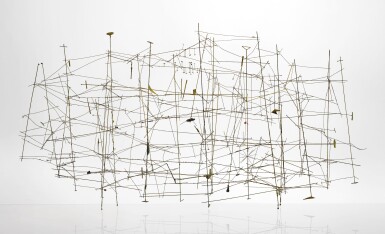

UNTITLED (WIRE CONSTRUCTION)

1956

brass-coated wire, enamel

32 x 63 x 10 in. (81.1 x 160 x 25.4 cm)

Acquired directly from the artist by Jean and George S. Rosenthal, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1956

Thence by descent to the present owner

June Kompass Nelson, Harry Bertoia, Sculptor, Detroit, 1970, p. 54, fig. 1 (for a related wire construction at St. John's Unitarian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio; the commission was facilitated by the owner of the present lot)

Nancy N. Schiffer and Val O. Bertoia, The World of Bertoia, Atglen, PA, 2003, pp. 51 (for the present lot illustrated with the artist and George Rosenthal in situ in Harry Bertoia's studio), 59 (for a period IBM advertisement featuring a related wire construction) and 87-88 (for related "cloud-form" wire constructions)

In Nature’s Embrace: The World of Harry Bertoia, exh. cat., Reading Public Museum, Reading, 2006, p. 33 (for a related wire construction)

Celia Bertoia, The Life and Work of Harry Bertoia, Atglen, PA, 2015, pp. 39 and 65 (for related wire constructions) and p. 101 (for the above mentioned related wire construction at St. John’s Unitarian Church)

Beverly H. Twitchell, Bertoia, New York, 2019, pp. 155 and 157 (for related wire constructions)

This lot is offered together with a certificate of authenticity from the Harry Bertoia Foundation, Bozeman, Montana.

Harry Bertoia (1915-1978) was prolific in his artistic investigations of nature and the cosmos. These studies were manifested in an incredibly diverse variety of mediums: drawings, monotypes, sculptures and even sounds borne of his iconic sonambient sculptures. “At most my work registers a process of inquiry,” he explained in 1958, “an expression of joy for life, an aim toward understanding, a mark for existence.” His incurable optimism was omnipresent in his work, with each “inquiry” leading intuitively to the next in a remarkably consistent, lifelong artistic evolution that was set in motion by Bertoia’s time spent at Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Bertoia arrived at Cranbrook in 1937, a few years after emigrating from his native northern Italy, where he had shown great promise as a young artist. He described his school days as exposing him “to the ‘hows’ more than to the ‘whys’ or the ‘whats.’” As a student he concentrated in metalsmithing with particular emphasis on jewelry-making, which was one of the most important “hows” in the artist’s education. The skills he learned making jewelry would be utilized throughout his career, and Bertoia’s embrace of metal as his primary medium during this time would also become permanent. His vision of the “whys” and “whats” of art were also stirring within him, but would not come into full expression until the next decade and beyond.

In addition to his adoption of metal, Bertoia’s discovery of wire could be considered one of the artist’s most important breakthroughs. He explained: “Wire is easy to work with, easy to experiment with. It can be flexed and formed quickly, by hand, allowing almost immediate visual inspection of the form of an idea.” After a two years as head of Cranbrook’s metalsmith department, he accepted the invitation of Charles and Ray Eames to join them in southern California in 1943, where he studied welding intensively. It was wartime, and so he worked for Evans Products Company manufacturing glider parts. While Bertoia continued to hone his metalworking skills through this experience, he was also assisting Eames was with his development of molded plywood. Bertoia’s exposure to and involvement in Eames’ experimental process was extremely influential. A few years later, in the 1950s, Bertoia began experimenting with hyperbolic wire constructions—an echo from his drawings of the 1940s that culminated in his iconic Diamond chair for Knoll.

He continued to push the linear vocabulary of this chair into a new realm, enamored by the way wire constructions “pertain to space rather than ground, and their configurations can be light, airy, almost floating.” Graphic yet sculptural, when Bertoia abandoned the strict organization of wire he used for the Diamond chair, his wire constructions became highly evocative of nature. By this time, Bertoia’s work with Knoll had brought him and his young family to rural Pennsylvania. The lush forests and peaceful meadows were an inspiration to the artist, who sought to bring himself ever closer to nature. His wire constructions took on informal names such as Cloud, Straw, Dandelion, Sunburst and even Comet. His general, loosely termed Wire Constructions are arguably Bertoia’s most abstract and transcendent explorations of the form.

The present Wire Construction leaves so much to the imagination, and indeed gives us great insight into the artist’s own imagination. Perhaps it is a celestial cloud or an architectural model of the heavens. An entire universe seems to be contained in Bertoia’s complex network of intersecting, delicately welded golden wires, punctuated with welded embellishments. The present example is particularly intriguing due to its inclusion of enameled elements. It was exceedingly rare for Bertoia to incorporate color into his works, but here he accents the composition with notes of red, yellow and pale grey-green enamel. Such use of polychrome was reserved for more graphic planar constructions and was most famously used in the no longer extant screen made for the St. Louis Airport (1956). In a sense, the polychrome elements in the present work serve as landmarks or reference points as one views the sculpture from all sides. From every vantage point, Wire Construction is reinvented, constantly changing with the viewer’s perspective: a red flag, a starburst, a blue stone, or abstract welded elements, create a dynamic ephemerality. The sculpture invites the viewer to contemplate their place in the universe, as Bertoia often did. The meditative and inspirational quality of Wire Construction is underscored by its aesthetic kinship to Bertoia’s exceptional wire screen reredos for the MIT Chapel (1955), which was executed around the same time as the present work.

It comes as no surprise that this masterwork caught the discerning eye of Cincinnati art collectors Jean and George S. Rosenthal. Like Bertoia, George Rosenthal was drawn to the European avant-garde at an early age. In the late 1930s, he attended the New Bauhaus (later the Institute of Design) in Chicago where he had the opportunity to study with Lásló Moholy-Nagy and befriended Man Ray. After the Second World War, Rosenthal was able to apply his studies and unique modernist vision through a number of professional endeavors including a publishing business, his own photography, and an art gallery program that he pioneered at Shillito’s, a local department store, which reflected a post-war trend at the time, of major department stores establishing high end art galleries within the store.

One of Rosenthal’s publishing endeavors was Portfolio magazine, which Rosenthal published with graphic designer Alexey Brodovitch and editor Frank Zachary, considered by many to be a high-point in American graphic design. It was a short lived but supremely influential publication that sacrificed commercial success in order to achieve its aesthetic aims. Nevertheless, it represented a revolution in editorial design and had a pervasive influence on modern visual culture. Portfolio was also notable for a number of significant features, including articles on Alexander Calder, an article on stereoscopy which included 3-D glasses inserted into the magazine, photographs by Isamu Noguchi. It also captured the work of emerging stars such as Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. Most famously, a photo feature which presented for the first time Hans Namuth’s iconic photographs of Jackson Pollock in his studio.

Rosenthal began collecting art during a trip to New York in 1949 where he attended the debut exhibition at the legendary Sidney Janis Gallery and acquired his first painting: a 1948 portrait by Fernand Léger entitled Tête de femme (Figure II). Rosenthal intended to use the painting on the cover of the first issue of Portfolio, but Alexey Brodovitch declined to use the Léger on the cover. However, he suggested Rosenthal keep the work for his own collection. In 1962, while in Los Angeles, Rosenthal visited Andy Warhol’s groundbreaking exhibition at the Ferus Gallery where he purchased Campbell's Soup Can (Pepper Pot). Over time, George and Jean Rosenthal’s prescient collection expanded to include works by both Modern and Contemporary masters including Josef Albers, Max Ernst, Francis Picabia, Jean Dubuffet, Jackson Pollock, Man Ray, Kurt Schwitters, Jean Arp, Pablo Picasso, among others.

Without question, the sculpture the Rosenthals most admired was Harry Bertoia, who also became a close, personal friend. George Rosenthal visited Bertoia’s Pennsylvania studio in the 1950s, at the height of Bertoia’s experimentation with wire. A photograph from that visit, showing both Bertoia and Rosenthal, as well as the present Wire Construction that Rosenthal would go on to acquire in 1956, captures the essence of their warm and collaborative friendship. In 1961, Rosenthal helped to secure an ecclesiastical commission for Bertoia, suggesting to his friend, the architect John Garber, that he should create a vertical wire altar screen for St. John’s Unitarian Church in Cincinnati. While the Rosenthal collection grew to include seven Bertoia sculptures, Wire Construction was always displayed with pride of place on the mantelpiece of their living room and was fondly nicknamed by the family “the crown.”