GORDON BENNETT | SELF PORTRAIT (BUT I ALWAYS WANTED TO BE ONE OF THE GOOD GUYS)

Auction Closed

December 13, 10:40 PM GMT

Estimate

350,000 - 450,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

GORDON BENNETT

1955-2014

SELF PORTRAIT (BUT I ALWAYS WANTED TO BE ONE OF THE GOOD GUYS)

Oil on canvas

59 in by 102 in (150 cm by 260 cm)

Painted in Brisbane in 1990

Bellas Gallery, Brisbane

Private Collection, Queensland

Moet & Chandon: Touring Exhibition, 13 February 1991 - 08 December 1991

Australian National Gallery, Canberra; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, Hobart; Westpac Gallery, Melbourne

Strangers in Paradise: Contemporary Australian Art to Korea, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul: 05 November 1992 - 04 December 1992

Confess and Conceal: 11 Insights from Contemporary Australia and South-East Asia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth: 27 March 1993 - 02 May 1993

History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett, Brisbane City Art Gallery, Brisbane: 29 July 1999 - 07 September 1999; Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK: 20 November 1999 - 23 January 2000; Arnolfini, Bristol, UK: 05 February 2000 - 19 March 2000; Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, Europe: 09 April 2000 - 12 June 2000

Three Colours, Heide MOMA: 08 April 2004 - 04 July 2004; Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria: 24 July 2004 - 29 August 2004; Academy Gallery, University of Tasmania, Tasmania: 10 February 2005 - 13 March 2005; Plimsoll Gallery, University of Tasmania, Tasmania: April 2005; Shepparton Art Gallery, Victoria: 07 July 2005 - 14 August 2005; Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria: 26 August 2005 - 30 October 2005; Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane: 10 November 2005 - 10 December 2005

Gordon Bennett: A Survey, The Ian Potter Centre: NGV, Melbourne at Federation Square: 6 September 2007 - 16 January 2008; QAGOMA, Brisbane: 10 May 2008 - 03 August 2008

AGWA, Perth: 20 December 2008 - 22 March 2009

Moet & Chandon Australian Art Foundation: Touring Exhibition 1991, Moet & Chandon, Sydney, 1991, pp 9; 12-13; 13 (illus.)

Helen Topliss "The Fifth Moet & Chandon", Art and Australia, Volume 29, No. 1, Spring 1991, Fine Arts Press Pty Limited, Sydney, pp 34-35; 34 (illus.)

Michael A. O'Ferrall, "On Other Perspectives" and Rex Butler, "The Pataphysical Aborigine", Gordon Bennett Paintings 1987 – 1991, Moet & Chandon, France and Francis Barbier & Jean-Claude Prévost (le Réveil de la Marne), 1992, pp 3-10; 11-17; 29 (illus.)

Victoria Lynn, "Artists in Paradise" and "Gordon Bennett (artist statement 1992)", Gordon Bennett, Strangers in Paradise: Contemporary Australian Art to Korea, 1992, pp 16; 24 (illus.); 84 - Artist biography ; 99

Jeanette Hoorn, "Positioning the Post-Colonial Subject: History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett", Art and Australia, Volume 31, No 2, Summer 1993, Fine Arts Press Pty Limited, Sydney, pp 216-226; 222-223 (illus.)

Margaret Moore and Michael O'Ferrall and Gordon Bennett (artist statement 1993) Confess and Conceal: 11 Insights from Contemporary Australia and South-East Asia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 1993, pp 10-17; 26 (illus.); 23 - List of works; 27 (illus.)

Donald Williams and Colin Simpson, Politics Meets Art: Anger Through Art - Art Now: Contemporary Art Post - 1970, McGraw-Hill Book Company Australia Pty Limited, NSW, 1994, pp 39-62; 41-43; 42 (

Robin Buckner, "Art and Design Appreciation, Chapter 1", Gordon Bennett Art and Design: Book One, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Sydney, 1995, pp 13-14; 14 (illus.)

Gordon Bennett, "The Manifest Toe"; The Art of Gordon Bennett, Craftsman House / G+B Arts International, Sydney, 1996, pp 8-63; 17 (illus.)

Gavin Jantjes and Elizabeth A Macgregor, Preface and Terry Smith, "Australia's Anxiety", History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett exhibition catalogue, 1st edition, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham and Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, 1999, pp 8-9; 10-21; 73-80 - List of

Zara Stanhope, "How Do You Think it Feels? Response and Riposte in the Art of Gordon Bennett" and Peter Robinson; Pennie Hunt, "Blood as a Trace; Jill Bennett", "Love and Irony: Gordon Bennett after 9/11" in Three Colours: Gordon Bennett and Peter Robinson, exhibition catalogue, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2004, pp 6-29; 9 (illus.)

Kelly Gellatly, "Citizen in the Making: The Art of Gordon Bennett"; Bill Wright and Gordon Bennett, "Conversation: Bill Wright Talks to Gordon Bennett"; Justin Clemens, "The Analphabeast: Identity and Relation in the Work of Gordon Bennett"; Jane Devery, "Chronology" in Gordon Bennett: A Survey exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2007, pp 8-24; 96-105; 106-110; 111-117; 118 – Collections; 119-125 – Footnotes; 126-130 - Exhibition checklist; Plate 3 (illus.)

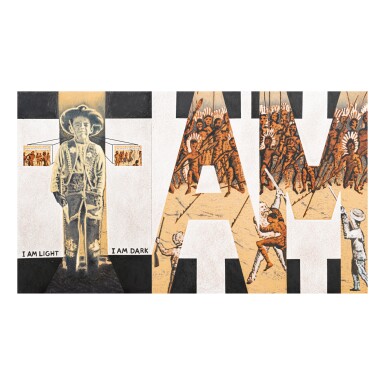

From its first public showing in 1991, Gordon Bennett’s Self portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys) struck a chord with the Australian art world. Along with The Nine Ricochets (Fall down black fella, jump up white fella), he had entered it in the Moet and Chandon Australian Art Fellowship Prize, winning what was then Australia’s most prestigious award for an emerging artist. Widely viewed during a national touring exhibition of the eighteen entrants, his two paintings dominated the reviews, which typically lauded his ‘spectacular success in the brief time since he decided to become a professional artist’.[i]

[i] Helen Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," Art &and Australia 29, no. 2, Spring (1991): 34.

When Self portrait was completed in October 1990, Bennett was less than two years out of art school. On the other hand, he had just turned thirty-five, his practice was driven by a sense of urgency, strong feelings, deep thoughts and clear ideas. Collectors were already moving in and during the next few years, critics, curators and theorists would seize on him as the new Messiah of Australian art. His rise was meteoric, turbocharged by the postcolonial turn. In 1993 he was the subject of a feature article ‘Positioning the Post-colonial Subject’ in Australia’s premier art magazine, Art and Australia, in which Self portrait was reproduced in a double-page spread, and he received an invitation to speak at London’s Tate Gallery in a conference planned for April 1994.[i] Organised by Rasheed Araeen and Jean Fisher of the postcolonial art journal Third Text, Bennett’s voice joined an emerging global postcolonial chorus.

Self portrait and The Nine Ricochets are now iconic Australian artworks. Considered springboards for Bennett’s later work, they also inspired a generation of artists. Like the first break of dawn, in the full light of day they acquired the aura of ‘First’ works. The metaphor is particularly apt, indeed prophetic, for Self portrait, in which Bennett depicts himself as a five-year-old child rising into the light from the shadows beneath his feet. At dawn the blazing sun distributes the shadows that create form from a dualism that Bennett literally spells out at the child’s feet: ‘I am Light / I am Dark’.

[i] Jeanette Hoorn, "Positioning the Post-Colonial Subject: History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett," Art and Australia 31, no. 2, Summer (1993); Jean Fisher, ed. Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts (London: Kala Press in association with The Institute of International Visual Arts, 1994).

Self-portrait does not pull punches: its meaning comes easily, and it keeps coming. It struck a chord, however, because its gifts chimed with the mood of an age in search of a moral purpose. A boy plays cowboy, his black hand (or is it in shadow?) ready to draw a toy gun. Eyes-shut, he conjures frontier scenes appropriated from Australian educational pictorial social studies books of the late 1950’s, which Bennett renders in two thought-bubbles that take the shape of gridded perspective diagrams that also form a crucifix. To the boy’s left, inside the sharp jagged diagonals of the abutting canvas, erupt the collective fears of a primitivist subliminal colonial imaginary. Does the boy hear its chilling howl? Is he already paying the price for wanting to be ‘the good guy’?

‘Self-portrait’ appears often in titles of Bennett’s art. ‘There’s a personal level in all my work’, he admitted.[i] His writing is also autobiographical, even confessional, as in this example, which is particularly apt for Self portrait:

There came a time in my life when I became aware of my Aboriginal heritage. This may seem of little consequence, but when the weight of European representations of Aboriginal people as the quintessential primitive ‘Other’ is realised and understood, within discourses of self and other, as a level of abstraction with which we become familiar in our books and our classrooms, but which we rarely feel on our pulses; then you may understand why such an awareness was problematic for my sense of identity. The conceptual gap between my sense of self and other collapsed and I was thrown into turmoil.[ii]

Those familiar with the postmodern theory of art school vernacular at the time will recognise a deeper narrative in Self portrait: Freud’s mythical psychoanalytical scene, in which Bennett had a deep interest.[iii] He projects it on a childhood memory, appropriated from an old family photograph.

[i] Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," 35.

[ii] Gordon Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, in Ian McLean and Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett (Sydney: Craftsman House, 1996), 9.

[iii] Ibid., 9.

The painting’s bold capitalised text exclaims ‘I AM’. Squeezed into the space of the ‘I’, the boy cowboy is the Ego Ideal or Super Ego that channels society’s moral values. ‘I’ is also the signifier of its mirror double, the signified ‘AM’, in which the primitive Id crowds in from the back, pushing forward but kept at bay by Ego. The doubling doesn’t stop: Ego is a wrestling couple, a large bearded white man and an Aboriginal man – or is it a woman? Bennett’s mother is Aboriginal, and his father was English. Or would the analyst interpret this struggling couple as Bennett’s split subject, or, like Jacob wrestling the Angel (i.e. God) through the night, Ego caught in the perpetual double bind of mediating the Id and the Super Ego?

Whatever the meaning of this dreamscape, blowing in from Paradise is a storm, in which the Holy Trinity of the Real, Symbolic and Imaginary batters the Ego. It transforms Self portrait from anecdotal stories into a state of being. ‘I look at photographs of myself as a child’, wrote Bennett, ‘as if it were someone else.’[i] The painting’s binaries do not resolve into a unified sense of self. There is no predicate to I AM that names who I AM, just another repeated double, ‘I am light’ / ‘I am dark’, in which each term simultaneously amplifies and erases the other. The same idea is in a preparatory note for Self portrait, in which Bennett uses Heidegger’s crossing out of a word to signal that its signification is simultaneously necessary and inadequate. Bennett likely got the idea from Derrida, for whom this erasure denoted the movement of deconstruction.

[i] Ibid., 17.

The note posits a metaphysical presence beneath the painting’s ‘psychodrama’ (to use Bennett’s neologism), which Bennett expresses in the monumental geometry of I AM and its gravitas as the Biblical name for God the Father. Metaphysics opens the immanent plane of self-identity to transcendental questions of Being, and so the personal to the universal. The theme characterises Bennett’s work and also steers his appropriation, here of Imants Tillers’s painting Hiatus (1987), which in turn appropriated Colin McCahon’s Victory over Death 2 (1970). Both paintings employ the same I AM structure, and like Bennett, Tillers and McCahon traverse a metaphysical terrain. This is too a complex story to unpack here but suffice to say that Bennett inserts himself into a lineage that descends through Tillers to an ancestor that each share in McCahon. This aesthetic genealogy also traces a three-generational exchange by these Western artists with the realm of First Peoples, as if in it Bennett found a substitute genealogy for what he said was colonialism’s erasure of the three generations remove from his Aboriginal heritage, and which he had experienced first-hand in his itinerant working-class childhood.[i] The more we delve into these deeper reverberations of Self portrait, the louder this ‘history painting’, as he dubbed it, declares its subject as the collective postcolonial self in which the colonial consciousness returns to haunt the living.

[i] Ibid., 20.

Self portrait was the culmination of a series that Bennett had been working on throughout 1990, in which he brought the conceptual moves made the previous year to greater formal resolution. In 1989, he had begun a semiological makeover of his student’s expressionism. He introduced single-point perspective diagrams ‘as symbolic of a certain kind of power structure relating to a particular European [colonialist] world view’,[i] and he filtered his former ‘realism’ through ‘the dot screen of … photo-mechanical reproduction’, drawing an analogy between the dot screen and the dotting of Aboriginal Western Desert painting.[ii] Both these aesthetic strategies are evident in Self portrait, as is his working of the dotting into free swirling currents as if to put it in a binary relation with the perspective grid. In The nine ricochets, an early painting in the series, he began using Pollock’s drip style to the same effect. The influence of Tillers in these aesthetic moves is pronounced. Both paintings also directly appropriated examples of Tillers’s seminal appropriation art of the previous decade. However, Bennett gave Tillers’s postmodern appropriation a postcolonial twist. The nine ricochets and Self portrait famously initiated an Oedipal struggle with this Father of Australian appropriation art, from which Bennett would emerge victorious. Educated in the mores of postmodernism, Bennett defended his embrace of appropriation art: ‘I have no Aboriginal traditions to draw upon … my culture is Western’.[iii]

[i] Ibid., 36.

[ii] Ibid., 43.

[iii] Quoted in Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," 34.

Bennett’s art hit a nerve because of its timing. The Australian nation was deeply unsettled about its colonial history in the wake of the 1988 bi-centenary celebrations of Britain’s invasion. The following year, the Berlin Wall came down and the world began to assume a new global postWestern consciousness. The artworld began interrogating its inherited Eurocentrism, kicked off by Jean-Hubert Martin’s Magiciens de la terre exhibition in Paris in 1989, and for Australians, by the very successful exhibition in New York in 1988, Dreamings: The art of Aboriginal Australia. At last, it seemed, Paris and New York had returned the periphery’s gaze.

This turn of events created a rare opening for the repressed, but it came with a cost. If Bennett knew that now his ‘Aboriginality … was a quick road to success’, it was on condition that he carry the burden of colonialism’s representations. As an example, he later cited an exhibition at the Guggenheim Soho Museum which, in 1995, had claimed that the ‘most peculiarly Australian characteristic’ of his work, and that of two other ‘Urban Aboriginal’ exhibitors, ‘is the lesson they carry from their bush-dwelling cousins’.[i] In Self portrait he sought to dodge this double bind by putting his Aboriginality under erasure or deconstruction. Accompanying the painting is a text, developed from the previously-mentioned note, which prefigures the type of textual rap he would soon incorporate into his work:

I AM AUSTRALIAN

I AM ABORIGINAL

I AM GORDON BENNETT

I AM … (AM I?)

[i] Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, 58.

“Aboriginality” … I don’t have to be an Aborigine to do what I do’. To resist his categorisation as ‘an “Urban Aboriginal Artist”’, indeed any fixed identity, he used ‘self-portraiture’ as ’a “strategic logocentre” in response to a society that seeks to transfix me with the patronising and conceited gaze of those who only seem able to think in terms of the conventional and “common sense” binaries of the “noble” or “ignoble” savage.’ [i]

Such was the scale and momentum of the paradigm shifts that occurred around 1990, it now seems that the new millennium had begun a decade early. On a self-declared mission to upturn the colonialist assumptions of Australian national culture, overnight Bennett became Australia’s most sought-after contemporary artist. The 1990s belonged to him. He is represented in all Australia’s major collections, and Bennett also geared his art to the global audience of the postcolonial turn. The cowboy theme of Self Portrait, with its appropriated image of Aborigines looking like Native Americans, has a deliberate American resonance, as if a premonition of his later Notes to Basquiat and 911 series. His work would be selected for Documenta 13 (2012) and purchased by Tate Modern in 2016. Bennett may have died in 2014 but his career has a long way to travel. The searing commentary of his art speaks more strongly to us than ever before.

[i] Ibid., 58.

“Aboriginality” … I don’t have to be an Aborigine to do what I do’. To resist his categorisation as ‘an “Urban Aboriginal Artist”’, indeed any fixed identity, he used ‘self-portraiture’ as ’a “strategic logocentre” in response to a society that seeks to transfix me with the patronising and conceited gaze of those who only seem able to think in terms of the conventional and “common sense” binaries of the “noble” or “ignoble” savage.’ [i]

Such was the scale and momentum of the paradigm shifts that occurred around 1990, it now seems that the new millennium had begun a decade early. On a self-declared mission to upturn the colonialist assumptions of Australian national culture, overnight Bennett became Australia’s most sought-after contemporary artist. The 1990s belonged to him. He is represented in all Australia’s major collections, and Bennett also geared his art to the global audience of the postcolonial turn. The cowboy theme of Self Portrait, with its appropriated image of Aborigines looking like Native Americans, has a deliberate American resonance, as if a premonition of his later Notes to Basquiat and 911 series. His work would be selected for Documenta 13 (2012) and purchased by Tate Modern in 2016. Bennett may have died in 2014 but his career has a long way to travel. The searing commentary of his art speaks more strongly to us than ever before.

[i] Ibid., 58.

“Aboriginality” … I don’t have to be an Aborigine to do what I do’. To resist his categorisation as ‘an “Urban Aboriginal Artist”’, indeed any fixed identity, he used ‘self-portraiture’ as ’a “strategic logocentre” in response to a society that seeks to transfix me with the patronising and conceited gaze of those who only seem able to think in terms of the conventional and “common sense” binaries of the “noble” or “ignoble” savage.’ [i]

Such was the scale and momentum of the paradigm shifts that occurred around 1990, it now seems that the new millennium had begun a decade early. On a self-declared mission to upturn the colonialist assumptions of Australian national culture, overnight Bennett became Australia’s most sought-after contemporary artist. The 1990s belonged to him. He is represented in all Australia’s major collections, and Bennett also geared his art to the global audience of the postcolonial turn. The cowboy theme of Self Portrait, with its appropriated image of Aborigines looking like Native Americans, has a deliberate American resonance, as if a premonition of his later Notes to Basquiat and 911 series. His work would be selected for Documenta 13 (2012) and purchased by Tate Modern in 2016. Bennett may have died in 2014 but his career has a long way to travel. The searing commentary of his art speaks more strongly to us than ever before.

[i] Ibid., 58.

Fisher, Jean, ed. Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts. London: Kala Press in association with The Institute of International Visual Arts, 1994.

Hoorn, Jeanette. "Positioning the Post-Colonial Subject: History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett." Art and Australia 31, no. 2, Summer (1993): 216–26.

Topliss, Helen. "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon." Art &and Australia 29, no. 2, Spring (1991): 34–35.

[1] Helen Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," Art &and Australia 29, no. 2, Spring (1991): 34.

[1] Jeanette Hoorn, "Positioning the Post-Colonial Subject: History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett," Art and Australia 31, no. 2, Summer (1993); Jean Fisher, ed. Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts (London: Kala Press in association with The Institute of International Visual Arts, 1994).

[1] Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," 35.

[1] Gordon Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, in Ian McLean and Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett (Sydney: Craftsman House, 1996), 9.

[1] Ibid., 9.

[1] Ibid., 17.

[1] Ibid., 20.

[1] Ibid., 36.

[1] Ibid., 43.

[1] Quoted in Topliss, "Contemporary Issues the Fifth Moet & Chandon," 34.

[1] Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, 58.

[1] Ibid., 32.

[1] Ibid., 58.