- 1136

HAO LIANG | Poison Buddha 2

Estimate

6,000,000 - 10,000,000 HKD

Log in to view results

bidding is closed

Description

- Hao Liang

- Poison Buddha 2

- ink on silk

- image: 162.5 by 90.5 cm. 64 by 35⅝ in.frame: 220.5 by 132 cm. 86¾ by 52 in.Executed in 2010.

Provenance

Gallery Beijing Space, Beijing

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Exhibited

Shenzhen, Guan Shanyue Art Museum, 7th International Ink Painting Biennale of Shenzhen, December 2010 - January 2011

Beijing, Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, SHUIMO Meet Revolution. The New Silk Road, April - May 2015, p.167 , illustrated in colour

Beijing, Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, SHUIMO Meet Revolution. The New Silk Road, April - May 2015, p.167 , illustrated in colour

Catalogue Note

In only a few years his oeuvre has spread like a long-folded fan. In forms filled with vitality, he continually interprets and simultaneously expresses a time-honoured worldview.

Zhu Zhu

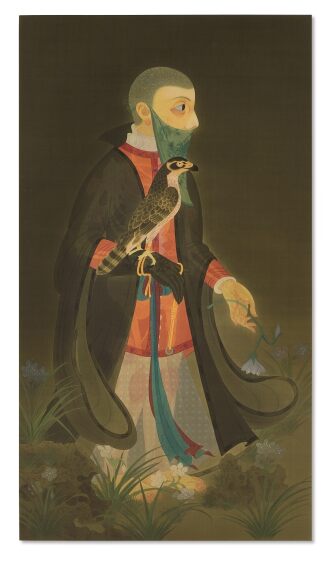

Emerging like a ghostly apparition from an infinitely deep and hauntingly secluded forest, the masked figure in Poison Buddha 2 holds a lone flower, a hawk perched on his arm. With the man's skeleton faintly visible under his robes, Poison Buddha 2 hails from Hao Liang's early and highly celebrated works focusing on the skeleton and the body as metaphors for the real and illusory worlds. This is a rare and superlative work by the artist - one of only two paintings depicting the Poison Buddha. Both Poison Buddha works were shown at “Purgatory On Line”, part of the Seventh International Ink Art Biennale of Shenzhen in 2010. At the time, Hao Liang's works attracted instant critical acclaim for their seamless fusion of meticulous gongbi painting, a classical Chinese realist technique, with the frescoed visual effects and anatomical insights of the Renaissance, which result in a highly unique and unorthodox aesthetic. The present Poison Buddha 2 was also exhibited at “SHUIMO: Meet Revolution, The New Silk Road” at the Beijing Minsheng Art Museum in 2015. Harnessing evocative themes such as the stories of pioneers, innovators, and developers, the exhibition explored the historic changes and developments of the Chinese ink painting tradition spanning 100 years. This consummate painting by Hao Liang was one of 150 participating works contributed by 60 artists, emphasizing his crucial contributions in advancing the connections between traditional Chinese classical ink painting and contemporary art.

Born in 1983, Hao was recently honoured in the 57th Venice Biennale’s central exhibition and is one of the youngest yet most important contemporary artists in China working in the medium of traditional ink wash painting. Having spent many years studying, researching, and reproducing Chinese classical paintings, Hao’s flawlessly executed silk portraits, hand scrolls, and landscape paintings are a remarkable fusion of techniques, traditions, and themes that bring the ancient medium of ink wash painting into the 21st century. His early interest in historical resources and painting techniques, along with the Western images and Japanese manga that inundated China in the 1980s, led to new visual impressions and experiences. Within these genres, Hao Liang did not lack for mystical subject matter, which in turn deepened his interest in mysterious and mystical narratives.

The skeleton is a central preoccupation for Hao Liang; one shared by the Southern Song painter Li Song. In Li Song's Skeleton Puppet Show, currently in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, an adult skeleton sits in the center of a busy market, entertaining a crowd with another little dancing skeleton marionette, coaxing children forward to try and grab it. The young woman behind the skeleton is serenely nursing her baby. Presenting various stages of the human life cycle, Li's poetic tableaux demonstrates not only aesthetic and spiritual preoccupations with life and death but also a particular world view. This work left a deep impression on Hao; in an interview with Hu Fang, Hao said: “In ancient China, the world was understood in an entirely different way — an individual stood not at its center but was merely one aspect of the world. This view formed the basis for its unique and splendid art and literature” (the artist cited in “Tempering the Mortal Body,” Secluded and Infinite Places, The Pavilion, 2014, p. 82). Distilling his studies of existentialism and Chinese notions of void and emptiness, Hao Liang found his own singular vehicle through which to pronounce his own worldview: that of the human figure that is half flesh and half skeleton. Through bone, flesh, form, and spirit, he diligently examines a metaphysical, human sense of being. Art critic Zhu Zhu has observed, “In only a few years [Hao Liang's] oeuvre has spread like a long-folded fan. In forms filled with vitality, he continually interprets and simultaneously expresses a time-honoured worldview” (Ibid, p. 9). Such profound contemplations on existence and the human condition began to prevail beginning from 2010-2011 when Hao Liang commenced his Poison Buddha series, which perfectly encapsulates his thinking.

Raised in a devoutly Buddhist family, Hao Liang's religious upbringing undoubtedly influenced his art. For the Chinese title of Poison Buddha 2, Hao chose the word Futu, which has the same meaning as other names for the Buddha such as Futuo or Juezhe, describing the masked young man emerging from the deep forest. On first glance an ordinary mountain recluse, a closer look reveals the skeleton faintly visible beneath the figure's finely brocaded robe, evincing a flash of the otherworldly. The ivory white bones echo the word “poison” in the title, conveying a warning and satirizing the absurdity of worldly concerns. In the search for new knowledge, people overemphasize their own powers and can be easily led astray. This is best exemplified in Goethe’s Faust whose lust for knowledge and power led him into a pact with the Mephistopheles, who ultimately brought Faust’s soul to hell.

Thus, existing within Hao Liang's seemingly traditional bodies is a transcendent realm of contemporary thinking. He evokes the ancient Chinese classics and brings them together with Western anatomy, reinterpreting traditional understandings of cultural symbols such as flesh, bones, flowers, and hawks. “Form used to depict the formless” shapes his presentation of the Buddhist contemplation of emptiness, wherein all things go through a cyclical process of rising and perishing. Such a concept is difficult to manifest. His half-flesh, half-bone artistic lexicon is a metaphor emphasizing life’s ephemerality. The muscles and sinews of the human body can nourish the belly of that hawk, perpetuating another cycle of life. Bones decay to dust, and then enrich the soil, which in turn nurture the growth of plants. The symbolism in Poison Buddha 2 show the ways in which the human form can transform, while also expressing in a mournful way the empty shadows of human spirituality. “All is like a flower - even the most exceptional beauty will inevitably wither”, Hao Liang said. Perhaps in defiant celebration of such fragile impermanence, the figure in the painting eschews the Buddhist mudra and instead gingerly clasps a single flower. In the face of relentless cycles and vicissitudes of life, one should hold flowers rather than wait until the branches are bare.

Zhu Zhu

Emerging like a ghostly apparition from an infinitely deep and hauntingly secluded forest, the masked figure in Poison Buddha 2 holds a lone flower, a hawk perched on his arm. With the man's skeleton faintly visible under his robes, Poison Buddha 2 hails from Hao Liang's early and highly celebrated works focusing on the skeleton and the body as metaphors for the real and illusory worlds. This is a rare and superlative work by the artist - one of only two paintings depicting the Poison Buddha. Both Poison Buddha works were shown at “Purgatory On Line”, part of the Seventh International Ink Art Biennale of Shenzhen in 2010. At the time, Hao Liang's works attracted instant critical acclaim for their seamless fusion of meticulous gongbi painting, a classical Chinese realist technique, with the frescoed visual effects and anatomical insights of the Renaissance, which result in a highly unique and unorthodox aesthetic. The present Poison Buddha 2 was also exhibited at “SHUIMO: Meet Revolution, The New Silk Road” at the Beijing Minsheng Art Museum in 2015. Harnessing evocative themes such as the stories of pioneers, innovators, and developers, the exhibition explored the historic changes and developments of the Chinese ink painting tradition spanning 100 years. This consummate painting by Hao Liang was one of 150 participating works contributed by 60 artists, emphasizing his crucial contributions in advancing the connections between traditional Chinese classical ink painting and contemporary art.

Born in 1983, Hao was recently honoured in the 57th Venice Biennale’s central exhibition and is one of the youngest yet most important contemporary artists in China working in the medium of traditional ink wash painting. Having spent many years studying, researching, and reproducing Chinese classical paintings, Hao’s flawlessly executed silk portraits, hand scrolls, and landscape paintings are a remarkable fusion of techniques, traditions, and themes that bring the ancient medium of ink wash painting into the 21st century. His early interest in historical resources and painting techniques, along with the Western images and Japanese manga that inundated China in the 1980s, led to new visual impressions and experiences. Within these genres, Hao Liang did not lack for mystical subject matter, which in turn deepened his interest in mysterious and mystical narratives.

The skeleton is a central preoccupation for Hao Liang; one shared by the Southern Song painter Li Song. In Li Song's Skeleton Puppet Show, currently in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, an adult skeleton sits in the center of a busy market, entertaining a crowd with another little dancing skeleton marionette, coaxing children forward to try and grab it. The young woman behind the skeleton is serenely nursing her baby. Presenting various stages of the human life cycle, Li's poetic tableaux demonstrates not only aesthetic and spiritual preoccupations with life and death but also a particular world view. This work left a deep impression on Hao; in an interview with Hu Fang, Hao said: “In ancient China, the world was understood in an entirely different way — an individual stood not at its center but was merely one aspect of the world. This view formed the basis for its unique and splendid art and literature” (the artist cited in “Tempering the Mortal Body,” Secluded and Infinite Places, The Pavilion, 2014, p. 82). Distilling his studies of existentialism and Chinese notions of void and emptiness, Hao Liang found his own singular vehicle through which to pronounce his own worldview: that of the human figure that is half flesh and half skeleton. Through bone, flesh, form, and spirit, he diligently examines a metaphysical, human sense of being. Art critic Zhu Zhu has observed, “In only a few years [Hao Liang's] oeuvre has spread like a long-folded fan. In forms filled with vitality, he continually interprets and simultaneously expresses a time-honoured worldview” (Ibid, p. 9). Such profound contemplations on existence and the human condition began to prevail beginning from 2010-2011 when Hao Liang commenced his Poison Buddha series, which perfectly encapsulates his thinking.

Raised in a devoutly Buddhist family, Hao Liang's religious upbringing undoubtedly influenced his art. For the Chinese title of Poison Buddha 2, Hao chose the word Futu, which has the same meaning as other names for the Buddha such as Futuo or Juezhe, describing the masked young man emerging from the deep forest. On first glance an ordinary mountain recluse, a closer look reveals the skeleton faintly visible beneath the figure's finely brocaded robe, evincing a flash of the otherworldly. The ivory white bones echo the word “poison” in the title, conveying a warning and satirizing the absurdity of worldly concerns. In the search for new knowledge, people overemphasize their own powers and can be easily led astray. This is best exemplified in Goethe’s Faust whose lust for knowledge and power led him into a pact with the Mephistopheles, who ultimately brought Faust’s soul to hell.

Thus, existing within Hao Liang's seemingly traditional bodies is a transcendent realm of contemporary thinking. He evokes the ancient Chinese classics and brings them together with Western anatomy, reinterpreting traditional understandings of cultural symbols such as flesh, bones, flowers, and hawks. “Form used to depict the formless” shapes his presentation of the Buddhist contemplation of emptiness, wherein all things go through a cyclical process of rising and perishing. Such a concept is difficult to manifest. His half-flesh, half-bone artistic lexicon is a metaphor emphasizing life’s ephemerality. The muscles and sinews of the human body can nourish the belly of that hawk, perpetuating another cycle of life. Bones decay to dust, and then enrich the soil, which in turn nurture the growth of plants. The symbolism in Poison Buddha 2 show the ways in which the human form can transform, while also expressing in a mournful way the empty shadows of human spirituality. “All is like a flower - even the most exceptional beauty will inevitably wither”, Hao Liang said. Perhaps in defiant celebration of such fragile impermanence, the figure in the painting eschews the Buddhist mudra and instead gingerly clasps a single flower. In the face of relentless cycles and vicissitudes of life, one should hold flowers rather than wait until the branches are bare.