- 23

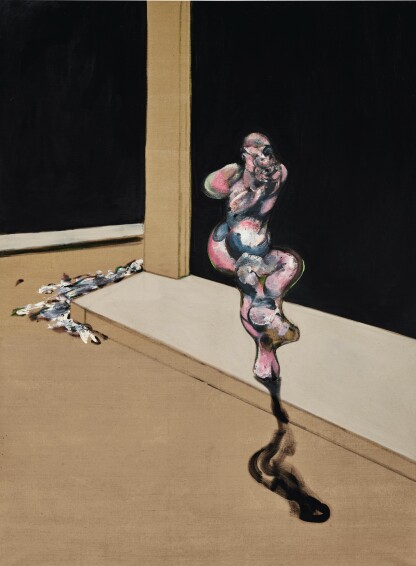

FRANCIS BACON | Turning Figure

Estimate

6,000,000 - 8,000,000 GBP

Log in to view results

bidding is closed

Description

- Francis Bacon

- Turning Figure

- oil on canvas

- 198 by 147.5 cm. 78 by 58 in.

- Executed in 1963.

Provenance

Marlborough Fine Art Ltd, London

Private Collection, London

Thomas Gibson Fine Art Ltd, London

Galerie Beyeler, Basel and Thomas Ammann Fine Art, Zurich (acquired from the above on 1 May 1985)

Acquired from the above by the present owner on 22 April 1986

Private Collection, London

Thomas Gibson Fine Art Ltd, London

Galerie Beyeler, Basel and Thomas Ammann Fine Art, Zurich (acquired from the above on 1 May 1985)

Acquired from the above by the present owner on 22 April 1986

Exhibited

London, Marlborough Fine Art Ltd, Francis Bacon: Recent Work, July - August 1963, n.p., no. 1 (text) and illustrated in colour (cover)

Hamburg, Kunstverein, Francis Bacon: Gemälde 1945–1964, January - February 1965, n.p., no. 47 (text)

Stockholm, Moderna Museet, Francis Bacon: Målningar 1945–1964, February - April 1965, p. 31, no. 49, illustrated

Dublin, The Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Francis Bacon, April - May 1965, n.p., no. 46 (text)

Basel, Galerie Beyeler, Francis Bacon: Retrospektive, 12 June - 12 September 1987, n.p., no. 15, illustrated in colour

Hamburg, Kunstverein, Francis Bacon: Gemälde 1945–1964, January - February 1965, n.p., no. 47 (text)

Stockholm, Moderna Museet, Francis Bacon: Målningar 1945–1964, February - April 1965, p. 31, no. 49, illustrated

Dublin, The Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Francis Bacon, April - May 1965, n.p., no. 46 (text)

Basel, Galerie Beyeler, Francis Bacon: Retrospektive, 12 June - 12 September 1987, n.p., no. 15, illustrated in colour

Literature

John Russell, Francis Bacon, London 1964, p. 32, illustrated

Ronald Alley, Francis Bacon, London 1964, n.p., no. 212, illustrated

Wieland Schmied, Francis Bacon: Commitment and Conflict, Munich 2006, p. 77, no. 89, illustrated

Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon – New Studies: Centenary Essays, Göttingen 2009, p. 33, no. 16, illustrated and p. 110 (text)

Katharina Günther, Francis Bacon: Metamorphoses, London 2011, p. 39, illustrated in colour

Martin Hammer, Francis Bacon and Nazi Propaganda, London 2012, pp. 47 and 203 (text) and p. 202, illustrated in colour

Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné, Volume III, 1958–1971, London 2016, p. 713, no. 63-03, illustrated in colour

Ronald Alley, Francis Bacon, London 1964, n.p., no. 212, illustrated

Wieland Schmied, Francis Bacon: Commitment and Conflict, Munich 2006, p. 77, no. 89, illustrated

Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon – New Studies: Centenary Essays, Göttingen 2009, p. 33, no. 16, illustrated and p. 110 (text)

Katharina Günther, Francis Bacon: Metamorphoses, London 2011, p. 39, illustrated in colour

Martin Hammer, Francis Bacon and Nazi Propaganda, London 2012, pp. 47 and 203 (text) and p. 202, illustrated in colour

Martin Harrison, Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné, Volume III, 1958–1971, London 2016, p. 713, no. 63-03, illustrated in colour

Condition

Colour: The colours in the catalogue illustration are fairly accurate, although the overall tonality is slightly deeper and richer in the original. Condition: Please refer to the department for a professional condition report.

"In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective, qualified opinion. Prospective buyers should also refer to any Important Notices regarding this sale, which are printed in the Sale Catalogue.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF BUSINESS PRINTED IN THE SALE CATALOGUE."

"In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective, qualified opinion. Prospective buyers should also refer to any Important Notices regarding this sale, which are printed in the Sale Catalogue.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF BUSINESS PRINTED IN THE SALE CATALOGUE."

Catalogue Note

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images Excerpt from The Wasteland by T.S. Eliot.

Painted in early 1963, Turning Figure by Francis Bacon illuminates the beginning of an extraordinary phase in the artist’s career, first signalled by the seminal 1962 triptych Three Studies for a Crucifixion (Collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York). This stage in Bacon’s oeuvre is marked both by personal tragedy and critical success; only six months prior to the execution of Turning Figure, Bacon’s first major institutional retrospective opened at the Tate Gallery, the preview of which coincided with the death of his first great – yet profoundly tumultuous – love and muse: Peter Lacy. Furthermore, Bacon’s relocation to 7 Reece Mews in 1961 – the house and studio he would retain for the rest of his life – helped end the widely cited ‘transitional’ period in Bacon’s work of the mid-late 1950s. Indeed, the paintings created at his South Kensington Mews house heralded the best work of Bacon’s career; from 1962 onwards, his pictures demonstrate greater assurance, resolution, and simplicity. This amplified level of invention is successfully illustrated in Turning Figure via a compositional matrix that imparts a sophisticated figure/ground relationship. As the final work in a loosely affiliated series that Bacon had begun in 1959, in which anonymous and contorted figures are depicted variously lying or standing, for example Two Figures of 1961 (The Estate of Francis Bacon Collection), the present work possesses an elevated degree of compositional ingenuity and deep pictorial allusion.

As with Francis Bacon’s great paintings, Turning Figure forces the viewer to confront the unadorned truth of the artist’s principal subject: the human animal. There is something sordid about the fleshy twist of this figure’s corporeality that demands the viewer acknowledge rather than repudiate the darker undercurrent of humanity and its fetid, abject nature. Turning inside-out, a corkscrew of androgynous limbs, muscle and bone pirouettes upon a single point and casts its shadow. A luminescent green outlines the figure; a vibrant contrast to the shocking pink of the figure’s fleshy passages that stands out against the abyssal black of the background. Indeed, sharply delineated against bands of black, cream and bare canvas, this figure seems to project away from the work’s surface, an effect no doubt enhanced by the collaged central form. Cut from another canvas and seamlessly applied – a method Bacon had previously employed for his 1961 painting, Reclining Nude in the Tate’s collection – this form possesses a cleanness of line and stark definition that Bacon could not have achieved any other way. This chromatic and compositional device here emphasises the deft simplicity of Bacon’s execution whilst also hinting at concurrent developments in contemporary art, particularly those of Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field painting. Created only one year prior, Bacon’s Study for P.L. strongly suggests the influence of Mark Rothko via bands of blue, green and golden-yellow that form the painting’s backdrop. Less explicit perhaps, yet notable is the background of Turning Figure which calls to mind Rothko’s striking Untitled (White, Blacks, Grays on Maroon), also painted in 1963, currently housed in the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich. Though Bacon would undoubtedly deny this connection and repudiate any such reading of his work, the settings and backdrops of his paintings from 1962 onwards display a striking planarity and vibrancy evocative of contemporaneous developments in abstract art.

Isolated against this pitch-black ground within an anonymous interior/exterior street scene, this figure is joined by what appears to be scattered newspaper littering the pavement; a presence that seems to creep around the corner and inch along the gutter as though in pursuit of the central form. It is this perspectival arrangement and enigmatic setting which serves to both strengthen and underpin the psychological and haunting intensity in Turning Figure; a painting that prefigures and anticipates much of the artist's later output, especially the urban landscapes of the 1980s such as Sand Dune (1983). However, as outlined by art historian Martin Hammer, the genesis of Bacon’s setting for the present work can be traced back to a photograph of wartime Rotterdam from a June 1940 issue of Picture Post (Martin Hammer, Francis Bacon and Nazi Propaganda, London 2012, p. 203). In this black and white image of a devastated street scene after a bombing raid, a man gazes upon the dead body of his daughter; her prone corpse appears foreshortened and almost indistinguishable from the rubble that surrounds her. In this respect, great importance has been assigned to the immense ‘archive’ of crumpled photographs, paint-splattered reproductions, and torn magazines that gathered in piles on the floor of Bacon’s studio. Following the artist’s death, the significance of these images – as the photo from the June 1940 issue of Picture Post attests – has been a revelatory tool in decoding some of the meaning behind, and origin of, Bacon’s extraordinary paintings. For an artist who detested working from life, the importance of this vast compendium of source material has since been widely unpacked and is particularly revealing when considering the impact of World War II on Bacon’s work.

Since the very beginning, as apparent in the 1944 masterpiece Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Bacon’s work has been steeped in visual references to the Second World War. Indeed, Nazi Germany and the figure of Hitler can be conceived as one of the principle subjects of Bacon’s art, heavily influencing much of his 1940s and early '50s output in both atmosphere and visual cues. Nonetheless, while Bacon had always been attuned to the great atrocities of the Second World War, the immediate postwar cultural climate had been one of systemic amnesia over the war and its criminals. By the late 1950s, however, this fog had begun to lift: following a wave of belated court cases against former Nazis in 1958, the prosecution and execution of high-ranking Nazi officials, most notoriously Adolf Eichmann who was subsequently executed in 1962, received international attention in the media; a collective awakening that firmly established what was thereafter known as the Holocaust, acknowledging it as a singular phenomenon within the Second World War’s theatre of violence. That this was clearly at the forefront of Bacon’s mind is apparent in the swastika-brandishing figure of the right panel in Bacon’s 1962 Crucifixion and the war-time source of the present work’s composition.

Using it as a springboard therefore, Bacon abstracted the forms and figures of the Picture Post image to deliver a painting of enigmatic allusion and complex metaphor. While maintaining the essential geometry and perspective of his source image, Bacon has nonetheless transfigured the girl’s body into the rubble and detritus that surrounds her; her form becoming one with the squalid fallout of an urban bombsite. Watched over by a twisting corporeal form that bears little resemblance to the watchful father in the black and white photo, Bacon’s twisted figure and the resounding atmosphere of post-war squalor calls to mind the strained and pulverized forms of Alberto Giacometti’s works of 1936 onwards. For example, the bedraggled loping form of Giacometti's Le Chien (1951) looks equally at home next to Bacon’s painting as it does beside an evocation of the dismal streets of war-torn Paris. Herein, the impact of Giacometti on Bacon’s work cannot be overestimated. Having moved beyond abstraction in a truly innovative way, Giacometti is often thought of as the principal influence on the School of London painters, and Bacon himself once described the Swiss master as “the greatest living influence on my work” (Francis Bacon cited in: Daniel Farson, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon, London 1994, p. 167). David Sylvester, whose interviews with Bacon are of canonical importance, also wrote extensively on Giacometti, focussing on the sense of loss and transience of life evoked by his paintings and sculptures. These evocations also permeate Bacon’s work as well, with existential crises providing the drive and recurring themes for his career.

The stark architecture, decontextualised street setting, and detritus which clusters in the gutter imbues Turning Figure with a palpable and weighty post-war atmosphere. In the catalogue raisonné of Bacon’s work, Martin Harrison pays particular attention to this detritus or trash, noting that Figure Turning foreshadows the appearance of newspapers and the use of Letraset in Bacon’s paintings from 1969 onwards. Where the inference of newspaper-like forms may call to mind the mess of the artist’s studio, it is in reference to the written word that this painting unlocks another important facet of Bacon’s practice: literature and poetry. As the exhibition ‘Bacon en toutes lettres’ at the Centre Pompidou has recently illuminated, the written word was held in equal regard by Bacon to that of photographic source material. Akin to the visual ephemera found in his studio, fragments of poetry and evocative cantos would "bring up images" and "open up valves of sensation" in exactly the same aleatory, associative, and chaotic way (Francis Bacon in conversation with David Sylvester in 1984, David Sylvester, Looking Back at Francis Bacon, London, 2000, p. 236). Hugely inspired by the grand melodrama and pathos of Aeschylus, Greek tragedy, and the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, Bacon's figures are imbued with an intense Dionysian abandon countered by the Apollonian calm interiors and isolated stages upon which his tragic dramas unfold. This can be traced as far back as the three Eumenides of his seminal 1944 triptych and carries through to the mythical grandeur of Triptych, 1976, a work centred on a complex musing and conflation of the Promethean and Oresteian myths. For Bacon, ancient myth presented the imaginative 'armature' upon which all kinds of sensations and feelings attuned to the violence of contemporary existence could be hung.

As a contemporaneous literary corollary to his paintings, T.S. Eliot's modern-day poetic recapitulation of classical mythology reverberates throughout Bacon’s work. The fragmentary and intensely concentrated emotive sensibility manifest in Eliot's Sweeney Agonistes and The Waste Land – literary works that would provide titles for two of Bacon's paintings in 1967 and 1982 respectively – find visual echoes and atmospheric redolence in Bacon’s grand theatre of distorted forms and enigmatic settings. According to Michael Peppiatt, when Bacon repeatedly claimed not to know where his images originated, he spoke of them materialising semi-consciously from the vast "memory traces" that had remained in his "grinding machine" – an analogy that Eliot himself had employed to define the "poet's mind" as a "receptacle for seizing and storing up numberless feelings, phrases, images, which remain there until all the particles which can unite to form a new compound are present together" (Francis Bacon and T.S. Eliot in: Michael Peppiatt, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London 2008, p. 282). For Bacon, poetry and words powerfully provided a direct link to sensation, breeding images and unlocking the valves of feeling in equal measure to the gamut of photographs and visual ephemera at his disposal.

Tortured and isolated, the subject of Turning Figure reflects the existential crises that peppered Bacon’s career while the mulch of unidentifiable paper and trash mirrors the solace from those crises that he found in literature. The influence of Giacometti is also undeniable given the weighty post-war atmosphere and violent manipulation of the human form; a body distorted by the impact of war. As with all of Bacon’s paintings, what we are primarily confronted with here is a body that does not perform as we expect it to. As Brenda Marshall describes, this is “a body that oozes, shifts frantically, a body that has muscles distended into grotesque animality, a body that knows about the smears of slippery substances that swill over and around it, a body that is made of water and blood and excrescences from unfathomable interiors” (Brenda Marshall, ‘Francis Bacon, Trash and Complicity’ in: Martin Harrison, Ed., Francis Bacon: New Studies, Göttingen 2009, p. 209). The urgent immediacy and primal drive of Bacon’s work is in full evidence here. Unapologetic and strident in its representation and recapitulation of the human form and more broadly the human condition, Turning Figure represents a milestone in Bacon’s oeuvre, both for its position in his canon and for the quality of its execution.

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images Excerpt from The Wasteland by T.S. Eliot.

Painted in early 1963, Turning Figure by Francis Bacon illuminates the beginning of an extraordinary phase in the artist’s career, first signalled by the seminal 1962 triptych Three Studies for a Crucifixion (Collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York). This stage in Bacon’s oeuvre is marked both by personal tragedy and critical success; only six months prior to the execution of Turning Figure, Bacon’s first major institutional retrospective opened at the Tate Gallery, the preview of which coincided with the death of his first great – yet profoundly tumultuous – love and muse: Peter Lacy. Furthermore, Bacon’s relocation to 7 Reece Mews in 1961 – the house and studio he would retain for the rest of his life – helped end the widely cited ‘transitional’ period in Bacon’s work of the mid-late 1950s. Indeed, the paintings created at his South Kensington Mews house heralded the best work of Bacon’s career; from 1962 onwards, his pictures demonstrate greater assurance, resolution, and simplicity. This amplified level of invention is successfully illustrated in Turning Figure via a compositional matrix that imparts a sophisticated figure/ground relationship. As the final work in a loosely affiliated series that Bacon had begun in 1959, in which anonymous and contorted figures are depicted variously lying or standing, for example Two Figures of 1961 (The Estate of Francis Bacon Collection), the present work possesses an elevated degree of compositional ingenuity and deep pictorial allusion.

As with Francis Bacon’s great paintings, Turning Figure forces the viewer to confront the unadorned truth of the artist’s principal subject: the human animal. There is something sordid about the fleshy twist of this figure’s corporeality that demands the viewer acknowledge rather than repudiate the darker undercurrent of humanity and its fetid, abject nature. Turning inside-out, a corkscrew of androgynous limbs, muscle and bone pirouettes upon a single point and casts its shadow. A luminescent green outlines the figure; a vibrant contrast to the shocking pink of the figure’s fleshy passages that stands out against the abyssal black of the background. Indeed, sharply delineated against bands of black, cream and bare canvas, this figure seems to project away from the work’s surface, an effect no doubt enhanced by the collaged central form. Cut from another canvas and seamlessly applied – a method Bacon had previously employed for his 1961 painting, Reclining Nude in the Tate’s collection – this form possesses a cleanness of line and stark definition that Bacon could not have achieved any other way. This chromatic and compositional device here emphasises the deft simplicity of Bacon’s execution whilst also hinting at concurrent developments in contemporary art, particularly those of Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field painting. Created only one year prior, Bacon’s Study for P.L. strongly suggests the influence of Mark Rothko via bands of blue, green and golden-yellow that form the painting’s backdrop. Less explicit perhaps, yet notable is the background of Turning Figure which calls to mind Rothko’s striking Untitled (White, Blacks, Grays on Maroon), also painted in 1963, currently housed in the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich. Though Bacon would undoubtedly deny this connection and repudiate any such reading of his work, the settings and backdrops of his paintings from 1962 onwards display a striking planarity and vibrancy evocative of contemporaneous developments in abstract art.

Isolated against this pitch-black ground within an anonymous interior/exterior street scene, this figure is joined by what appears to be scattered newspaper littering the pavement; a presence that seems to creep around the corner and inch along the gutter as though in pursuit of the central form. It is this perspectival arrangement and enigmatic setting which serves to both strengthen and underpin the psychological and haunting intensity in Turning Figure; a painting that prefigures and anticipates much of the artist's later output, especially the urban landscapes of the 1980s such as Sand Dune (1983). However, as outlined by art historian Martin Hammer, the genesis of Bacon’s setting for the present work can be traced back to a photograph of wartime Rotterdam from a June 1940 issue of Picture Post (Martin Hammer, Francis Bacon and Nazi Propaganda, London 2012, p. 203). In this black and white image of a devastated street scene after a bombing raid, a man gazes upon the dead body of his daughter; her prone corpse appears foreshortened and almost indistinguishable from the rubble that surrounds her. In this respect, great importance has been assigned to the immense ‘archive’ of crumpled photographs, paint-splattered reproductions, and torn magazines that gathered in piles on the floor of Bacon’s studio. Following the artist’s death, the significance of these images – as the photo from the June 1940 issue of Picture Post attests – has been a revelatory tool in decoding some of the meaning behind, and origin of, Bacon’s extraordinary paintings. For an artist who detested working from life, the importance of this vast compendium of source material has since been widely unpacked and is particularly revealing when considering the impact of World War II on Bacon’s work.

Since the very beginning, as apparent in the 1944 masterpiece Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Bacon’s work has been steeped in visual references to the Second World War. Indeed, Nazi Germany and the figure of Hitler can be conceived as one of the principle subjects of Bacon’s art, heavily influencing much of his 1940s and early '50s output in both atmosphere and visual cues. Nonetheless, while Bacon had always been attuned to the great atrocities of the Second World War, the immediate postwar cultural climate had been one of systemic amnesia over the war and its criminals. By the late 1950s, however, this fog had begun to lift: following a wave of belated court cases against former Nazis in 1958, the prosecution and execution of high-ranking Nazi officials, most notoriously Adolf Eichmann who was subsequently executed in 1962, received international attention in the media; a collective awakening that firmly established what was thereafter known as the Holocaust, acknowledging it as a singular phenomenon within the Second World War’s theatre of violence. That this was clearly at the forefront of Bacon’s mind is apparent in the swastika-brandishing figure of the right panel in Bacon’s 1962 Crucifixion and the war-time source of the present work’s composition.

Using it as a springboard therefore, Bacon abstracted the forms and figures of the Picture Post image to deliver a painting of enigmatic allusion and complex metaphor. While maintaining the essential geometry and perspective of his source image, Bacon has nonetheless transfigured the girl’s body into the rubble and detritus that surrounds her; her form becoming one with the squalid fallout of an urban bombsite. Watched over by a twisting corporeal form that bears little resemblance to the watchful father in the black and white photo, Bacon’s twisted figure and the resounding atmosphere of post-war squalor calls to mind the strained and pulverized forms of Alberto Giacometti’s works of 1936 onwards. For example, the bedraggled loping form of Giacometti's Le Chien (1951) looks equally at home next to Bacon’s painting as it does beside an evocation of the dismal streets of war-torn Paris. Herein, the impact of Giacometti on Bacon’s work cannot be overestimated. Having moved beyond abstraction in a truly innovative way, Giacometti is often thought of as the principal influence on the School of London painters, and Bacon himself once described the Swiss master as “the greatest living influence on my work” (Francis Bacon cited in: Daniel Farson, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon, London 1994, p. 167). David Sylvester, whose interviews with Bacon are of canonical importance, also wrote extensively on Giacometti, focussing on the sense of loss and transience of life evoked by his paintings and sculptures. These evocations also permeate Bacon’s work as well, with existential crises providing the drive and recurring themes for his career.

The stark architecture, decontextualised street setting, and detritus which clusters in the gutter imbues Turning Figure with a palpable and weighty post-war atmosphere. In the catalogue raisonné of Bacon’s work, Martin Harrison pays particular attention to this detritus or trash, noting that Figure Turning foreshadows the appearance of newspapers and the use of Letraset in Bacon’s paintings from 1969 onwards. Where the inference of newspaper-like forms may call to mind the mess of the artist’s studio, it is in reference to the written word that this painting unlocks another important facet of Bacon’s practice: literature and poetry. As the exhibition ‘Bacon en toutes lettres’ at the Centre Pompidou has recently illuminated, the written word was held in equal regard by Bacon to that of photographic source material. Akin to the visual ephemera found in his studio, fragments of poetry and evocative cantos would "bring up images" and "open up valves of sensation" in exactly the same aleatory, associative, and chaotic way (Francis Bacon in conversation with David Sylvester in 1984, David Sylvester, Looking Back at Francis Bacon, London, 2000, p. 236). Hugely inspired by the grand melodrama and pathos of Aeschylus, Greek tragedy, and the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, Bacon's figures are imbued with an intense Dionysian abandon countered by the Apollonian calm interiors and isolated stages upon which his tragic dramas unfold. This can be traced as far back as the three Eumenides of his seminal 1944 triptych and carries through to the mythical grandeur of Triptych, 1976, a work centred on a complex musing and conflation of the Promethean and Oresteian myths. For Bacon, ancient myth presented the imaginative 'armature' upon which all kinds of sensations and feelings attuned to the violence of contemporary existence could be hung.

As a contemporaneous literary corollary to his paintings, T.S. Eliot's modern-day poetic recapitulation of classical mythology reverberates throughout Bacon’s work. The fragmentary and intensely concentrated emotive sensibility manifest in Eliot's Sweeney Agonistes and The Waste Land – literary works that would provide titles for two of Bacon's paintings in 1967 and 1982 respectively – find visual echoes and atmospheric redolence in Bacon’s grand theatre of distorted forms and enigmatic settings. According to Michael Peppiatt, when Bacon repeatedly claimed not to know where his images originated, he spoke of them materialising semi-consciously from the vast "memory traces" that had remained in his "grinding machine" – an analogy that Eliot himself had employed to define the "poet's mind" as a "receptacle for seizing and storing up numberless feelings, phrases, images, which remain there until all the particles which can unite to form a new compound are present together" (Francis Bacon and T.S. Eliot in: Michael Peppiatt, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London 2008, p. 282). For Bacon, poetry and words powerfully provided a direct link to sensation, breeding images and unlocking the valves of feeling in equal measure to the gamut of photographs and visual ephemera at his disposal.

Tortured and isolated, the subject of Turning Figure reflects the existential crises that peppered Bacon’s career while the mulch of unidentifiable paper and trash mirrors the solace from those crises that he found in literature. The influence of Giacometti is also undeniable given the weighty post-war atmosphere and violent manipulation of the human form; a body distorted by the impact of war. As with all of Bacon’s paintings, what we are primarily confronted with here is a body that does not perform as we expect it to. As Brenda Marshall describes, this is “a body that oozes, shifts frantically, a body that has muscles distended into grotesque animality, a body that knows about the smears of slippery substances that swill over and around it, a body that is made of water and blood and excrescences from unfathomable interiors” (Brenda Marshall, ‘Francis Bacon, Trash and Complicity’ in: Martin Harrison, Ed., Francis Bacon: New Studies, Göttingen 2009, p. 209). The urgent immediacy and primal drive of Bacon’s work is in full evidence here. Unapologetic and strident in its representation and recapitulation of the human form and more broadly the human condition, Turning Figure represents a milestone in Bacon’s oeuvre, both for its position in his canon and for the quality of its execution.