- 9

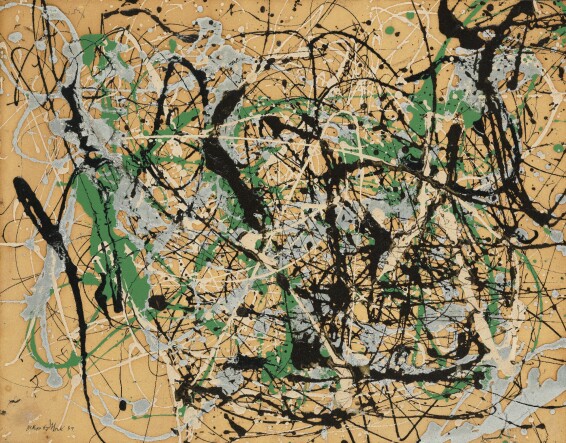

Jackson Pollock

Description

- Jackson Pollock

- Number 17, 1949

- signed and dated 49

- enamel and aluminum paint on paper mounted on fiberboard

- 22 1/4 x 28 3/8 in. 56.5 x 72 cm.

Provenance

Miss Dorothy Noyes, New Design Gallery

Marlborough Fine Art, Ltd., London

Sir John Heygate, Londonderry, Northern Ireland

Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New York

AG Foundation, Ohio (acquired from the above in 1970)

Sotheby's, New York, May 13, 2003, Lot 19 (consigned by the above)

Acquired by the present owner from the above

Exhibited

Tokyo, Bridgestone Museum, International Contemporary Art, October - November 1957

New York, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., Jackson Pollock, January - February 1964, cat. no. 100, illustrated (as Painting, 1949)

Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland Collects Contemporary Art, July - August 1972, cat. no. 85 (as No. 17A, 1949) and illustrated on the cover (detail)

New York, The Museum of Modern Art; Oxford, The Museum of Modern Art; Düsseldorf, Stadtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf; Lisbon, Gulbenkian Foundation; Paris, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Jackson Pollock: From Drawing into Painting, April 1979 - March 1980, cat. no. 36, p. 57, illustrated in color (Oxford, Düsseldorf and Paris) and cat. no. 36, p. 16, illustrated in color and p. 43, illustrated (Amsterdam)

Cincinatti, The Contemporary Arts Center, Drawings: Selections, July - August 1982

New York, CDS Gallery, The Irascibles, February 1988 (curated by Irving Sandler)

New York, Jan Krugier Gallery; Geneva, Galerie Jan Krugier, Victor Hugo and the Romantic Vision, May - July 1990, cat. no. 75

New York, C & M Arts, Jackson Pollock: Drip Paintings on Paper, 1948-1949, October - December 1993, n.p., illustrated in color

New York, The Museum of Modern Art; London, Tate Gallery, Jackson Pollock: A Retrospective, November 1998 - June 1999, cat. no. 166, p. 265, illustrated in color and fig. 26, p. 57, illustrated (in installation at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1949)

Literature

Francis Valentine O'Connor and Eugene Victor Thaw, eds., Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Drawings and Other Works, Volume 2, Paintings, 1948-1955, New Haven, 1978, cat. no. 243, p. 65, illustrated

Jeffrey Potter, To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock, New York, 1985, n.p., illustrated (in installation at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1949)

Peter Blake, No Place Like Utopia: Modern Architecture and the Company We Kept, New York, 1993, p. 111, illustrated (in installation at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1949)

Martin Fuller, "Art at Heart," House Beautiful, June 2000, p. 144, illustrated in color (detail)

Exh. Cat., London, Tate Liverpool (and travelling), Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, 2015, pp. 88 and 92, illustrated (in installation at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1949)

Condition

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

Catalogue Note

from the Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, circa 1920-1991, bulk 1946-1983. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Betty Parsons on Jackson Pollock, circa 1949

I loved his looks. There was a vitality, an enormous physical presence. He was medium height but he looked taller. You could not forget his face. A very attractive man, ---oh very.

He was always sad. He made you feel sad; even when he was happy he made you feel like crying. There was a desperation about him; there was something desperate. When he wasn’t drinking he was shy, he could hardly speak. And when he was drinking he wanted to fight. He cussed a lot, used every 4-letter word in the book. You felt he wanted to hit you; I would run away.

His whole rhythm was either sensitive or very wild. You never quite knew whether he was going to kiss your hand or throw something at you. The first time I went out to see him at Springs, Barney (Barnett Newman) brought me; we were planning Jack’s first show. After dinner we all sat on the floor, drawing with some Japanese pens. He broke three pens in a row. His first drawings were sensitive, then he went wild. He became hostile, you know. Next morning he was absolutely fine.

I had met him around New York since 1945. One day in ’47 he telephoned me and said he wanted a show in my gallery. I gave him a show the next season. In all the time he was with me he was never drunk either during the show or during the hanging. At Sidney Janis’s it was different, once they waited for him until 4 in the morning to hang a show.

Another year he telephoned me and asked me to give Lee a show of her paintings. I said I never show husbands and wives, but he insisted. He was charming with Lee when he was sober; she ruled the nest. But when he was drunk he ruled the nest. Lee always protected his business interests. Business ideas bored him, though he was fairly wise about them.

He was either bored or terrified of society. He thought most women were terrible bores. He needed aggressive women to break through his shyness. He liked very few artists. He liked Newman, he liked Bradley Tomlin. He thought artists were either awful or terrible – it had entirely to do with their work.

He thought he was the greatest painter ever, but at the same time he wondered. Painting was what he had to do. But he had a lot of the negative in him. He was apt to say, ‘It won’t work – it’ll never work.’ When he got in those terrible negative states, he would drink.

He associated the female with the negative principle. The conflict showed clearly in ‘The She Wolf’ (1943). Inside himself there was a jungle. Some kind of jungle because during his life he was never fulfilled – never – in anything. Of course this didn’t diminish his power as a painter. His conflicts were all in his life, not in his work.

He was a questioning man. He would ask endless questions. He wanted to know what I thought about the world, about life. He thought I was such a jaded creature because I’d travelled, he wanted to know what the outside world was like, Europe, Asia. He was also extremely intrigued with the inner world – what is it all about. He had a sense of mystery. His religiousness was in those terms – a sense of the rhythm of the universe, of the big order – like the Oriental philosophies. He sensed rhythm rather than order, like the Orientals rather than the Westerners. He had Indian friends, a dancer and his wife, (Mr. and Mrs. N. Vashti) with whom he talked at length and who influenced him greatly.

His most passionate interest after painting was baseball. He adored baseball and talked about it often. He also loved poetry and meeting poets. He often talked about Joyce. He loved architecture and talked a lot about that too. He adored animals. He had two dogs and an old crow – he had tamed an old crow. He had that kind of overall feeling about the nature – about the cosmic – the power of it all – how scary it is.

I could never relax with Jack. He certainly was pursued by devils.

Life is an endless question mark, but most of us find a resolution – he never did. But I loved him dearly. The thing about Pollock is that he was completely unmotivated – he was absolutely pure.

From my Journal – Sept. 25, 1949 – A week-end in Easthampton

Evelyn Segal

In the late afternoon we drove to the Jackson Pollocks, who live in a simple farm house (circa late 19th cent.) – a farm house which was being transformed and converted by the needs and tastes of the two painters: Jackson Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner. We had only just arrived, having been greeted warmly by “Lee” as Hattie called Mrs. P., when Mr. Clement Greenberg arrived with his guests: Robert Motherwell, the Peter Scotts and a Miss Blumberg. Mrs. Pollock served drinks. I noticed a table with a handsome mosaic top and learned that Mrs. Pollock had made it. (She, too, is a fine painter) Then Mr. Pollock appeared; he consented tacitly to our seeing his paintings.

We trooped to a barn. On the floor were huge canvases on which he had been working. There were many cans on the splattered floor – splatter of the duco, silverpaint, white lead, oils of various hue, et al, which he had used to make those mazes of linear space which some regard as chaos and with which he has caused such a “sensation.” We looked hard and silently, Mr. Motherwell, Mrs. Greenberg, Mr. and Mrs. Scott. One felt the strength of those paintings but moreover the serious violent effort toward a goal and significant statement. I am not certain just what I believe about them at this point, whether it is the materials themselves which have inherent strength and give them the power they appear to have or whether Mr. Pollock is an innovator in the application of his knowledge, experience and creative capacity – I do not know.

The canvases are the size of murals. There is consistent color key, and suggestion of planned form (but not form in terms of definite, natural or usual shapes) – an orderly jungle of planes – linear planes, which created vast space and movement. There are depth and seriousness in the feelings which are evoked but few usual plastic images, the absence of which extends rather than limits the scope of meaning to the spectator. I saw many of the paintings flat on the floor from where he works which made it difficult to see them in the conventional way. I remember wide lines of black and silver paint with splattered frayed edges in many of the lines, but those splatters made for forms which became planes. Some had the texture and surface of enamels.

They are bold! The principle of freedom, experiment and courage is evinced. Perhaps unconsciously – subjectively they are propelled by despair and anger and even exasperation. But assimilated experience and knowledge have facilitated these directions.

Mr. Motherwell looked silently, as we did, all of us. He walked toward a painting, started to say something and then restrained himself, finally saying, “Oh well – one shouldn’t ask a question about something a painter is still working on.”

There were simple non-natural forms cut in a masonite panel on which he was painting, which made for definite recesses since they had actually been cut in like a linoleum block. The paint had been continued, sparingly onto the recessed parts, not obscuring the forms which had been cut there, but rather making again for planes – and ultimately space, the Masonite itself providing another color and texture.

When asked later by Peter and Bob and Hattie and Jon what I said – what anyone had said – I reported that little had been said rightfully. A few technical questions had been asked and Mr. Pollock answered very succinctly. I mentioned the subtle differences in color key in each painting. That was the only definite, sincere statement I could make at the time… or would under the circumstances.

Everyone thanked Mr. Pollock. There were some “They’re terrifics” and Mrs. Scott obviously avoided the issue (most understandable) by saying, “Oh dear, it’s just too much to absorb in one afternoon.”

I think Mr. Pollock is sincere. There is power there. Whether or not he believes that these are ultimate realizations of his aims, I do not know, but I am inclined to doubt it. These paintings are not to be dismissed. The experimentation, daring, evidences of originality and intense creative effort are there.

Pollock’s paintings could be architectural accessories, and hung well and naturally on walls of contemporary architecture. They are not tender or romantic but neither are steel and concrete and plastics, or the materials used in contemporary structures. The paintings are personal but not intimate, and not familiar.

BEAUTY -- AND JACKSON POLLOCK, TOO

By Eli Siegel, December 1955

Thoughts about a phrase from the Critical Writing of Stuart Preston on Jackson Pollock, New York Times, December 4, 1955

No use looking for “beauty”…

1. There is a contemporaneous distrust of the word ‘beauty’ which it is well to look into.

2. There is a feeling prevalent that while the word beauty might have been all right with the Greeks or in the Eighteenth Century or with the Pre-Raphaelites, we are beyond this; we are too tough for this, too modern.

3. It is felt that the unconscious working on, say, bits of paper, or a heap of broken brick or dishes in a sink, will get to art, perhaps, that is not beautiful as past art has been; even so, there is no reason why one can’t or shouldn’t take broken brick as a subject, or scraps of paper: art really doesn’t mind, nor beauty, either.

4. The unconscious when it is completely unrestrained, untrammeled is opposed by critics to the idea of beauty, if not to that of impact, or of power, or of the elemental.

5. However, the aesthetic unconscious, if looked into, goes just as much for beauty in the primary, continuing, and still fresh sense of the conscious does.

6. The unconscious, as artistic, goes after unrestraint, but unrestraint as accurate; and when unrestraint is accurate, the effect on mind is still that of beauty.

7. No matter how unrestrained, elemental, untrammeled, without ‘forethought’ Jackson Pollock is, or anyone else – if his work is successful, there is in this work power and calm, intensity and rightness, unrestraint and accuracy – and these, felt at once, make for beauty.

8. Because beauty has taken new forms, used material foreign to Veronese, Gainsborough, Ingres, Ryder, there is a disposition on the part of critics like Stuart Preston to think the word beauty is no longer alive and electrical.

9. It is alive; it stands for life at its liveliest, at the most free and the most true.

10. For example, the question comes up: What makes Jackson Pollock’s unrestrained unconscious, ‘elemental and largely subconscious promptings,’ better than somebody else’ unrestrained unconscious and ‘subconscious promptings’?

11. For everybody has an unconscious – very often unrestrained – and everybody has ‘subconscious promptings.’

12. The question for Mr. Preston and others is: What makes the unconscious or subconscious of Mr. Pollock, and the working without ‘forethought’ of Mr. Pollock, better, more artistic, more commendable in result than similar things of the mind in so, so many others?

13. It is the presence of some rightness, fitness, structure, purpose, composition, design or whatever you wish to call it in Mr. Pollock – at least if you see his work as art, that is what you see in it besides the ‘subconscious,’ the ‘promptings,’ the ‘elemental.’

14. If Mr. Pollock’s unconscious is artistically successful, it is because there is a logic in it, a rightness or knowingness; words of Mr. Preston himself, like ‘apparently aimless’ imply some such thing – just look at the apparently!

15. So we have spontaneity, elementalness, freedom, ardor in Mr. Pollock, and rightness, accuracy, logic, design, effect, too.

16. Spontaneity and rightness, intensity and accuracy are what we find in Delacroix, Bosch, Turner, Van Gogh, and – yes, Piero della Francesca.

17. Spontaneity and rightness seen in a work of art, make one feel it has form.

18. Form is a word still synonymous with beauty.

19. Beauty can be regarded as the apprehended presence of individual impetus and universal rightness, of unconscious and conscious – and at its bet, the apprehended presence of the utmost spontaneity with the utmost truthfulness, rightness.

20. However, unrestrained Mr. Pollock’s unconscious is, it is going after design.

21. Otherwise, as was said (and it cannot be said too often) Mr. Pollock’s ‘abandonment of forethought’ would be like the lack of ‘forethought’ we find anywhere, with people not particularly artistic – and there is a mighty lot of ‘subconscious promptings’ in family squabbles, in sick rooms, in dull tavern brawls, in financial controversies.

22. People live differently today, but life goes on: the word life is as good as ever.

23. People go after beauty differently (for example, Jackson Pollock), but beauty is still around; the word beauty is as good as ever.

24. Mr. Preston is his effort to be desperately contemporary, has forgot to be deeply, vitally continuous – has forgot to be elemental in the very best sense.