- 12

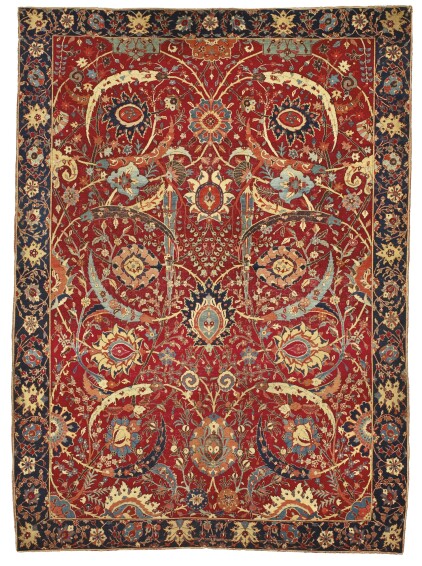

A Sickle-Leaf, vine scroll and palmette 'Vase'-technique carpet, probably Kirman, Southeast Persia

Description

- wool, silk, cotton

- approximately 8ft. 9in. by 6ft. 5in. (2.67 by 1.96m.)

Provenance

Exhibited

Washington, D.C., The Textile Museum, From Persia's Ancient Looms, January 23 - September 30, 1972

New York, Asia House Gallery, Shah 'Abbas & the Arts of Isfahan, October 11 - December 2, 1973

Cambridge, Massachusetts, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Shah 'Abbas & the Arts of Isfahan, January 19 - February 24, 1974

Sheffield, Mappin Art Gallery, Carpets of Central Persia, 1976; also travelled to Birmingham; City Museum and Art Gallery

Washington, D.C., The Corcoran Gallery of Art, The William A. Clark Collection, April 26 - July 16, 1978

London, Hayward Gallery, The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, May 20 - July 10, 1983

Washington D.C., Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, The World at our Feet. A Selection of Carpets from the Corcoran Gallery of Art, April 4 - July 6, 2003

Washington, D.C., Corcoran Gallery of Art, Masterpieces: European Arts from the Collection, August 25, 2007 - January 6, 2008

Literature

"Carpets for the Great Shah: The Near-Eastern Carpets from the W. A. Clark Collection," The Corcoran Gallery of Art Bulletin, Washington, D.C., Vol. 2, No. 1, October 1948, pp. 6 and 23, illustrated p. 8

Pope, Arthur Upham and Ackerman, Phyllis, A Survey of Persian Art, London and New York, 1939, pl. 1234

Erdmann, Kurt, ' "The Art of Carpet Making," A Survey of Persian Art. Rezension,' Ars Islamica, vol. 8, Ann Arbor, 1941, pp. 174-188 (cited)

Erdmann, Kurt, Oriental Carpets, An Account of their History, London 1960, fig. 85

Schlosser, Ignaz, European and Oriental Rugs and Carpets, London, 1963, no. 53

Ellis, Charles Grant, 'Kirman's Heritage in Washington: Vase Rugs in the Textile Museum,' Textile Museum Journal II: 3, December 1968, p. 19, fig. 2

Ettinghausen, Richard, From Persia's Ancient Looms, Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum, 1972, fig. 6

Dimand, M.S. and Mailey, Jean, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973, p. 77, fig. 107

Welch, Anthony, Shah 'Abbas & the Arts of Isfahan, New York: The Asia Society, 1973, no. 30, p. 17

Beattie, May H., Carpets of Central Persia, Sheffield: World of Islam Publishing Company, 1976, pl. 6, cat. no. 15

Ettinghausen, Richard, "Oriental Carpets in the Clark Collection," The William A. Clark Collection, Washington, D.C.: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1978, pp. 84-86, fig. 71

Yetkin, Serare, Early Caucasian Carpets in Turkey, vol. II, London: Oguz Press, 1978, p. 91, fig. 217

Eskenazi, J., et al, Il Tappeto Orientale dal XV al XVIII Secolo, Milan, 1982, fig. 1, p. 44

King, Donald and David Sylvester, eds., The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, London, 1983, no. 80, pp. 46, 100-101

Coyle, Laura and Dare Myers Hartwell, Antiquities to Impressionism: The William A. Clark Collection, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2001, pp. 74-75

"The Senator's Carpets, Hali, issue 127, p. 41, fig. 4

Franses, Michael, "Classical Context," Hali, issue 129, pp. 68-69, fig. 4 (detail)

Condition

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

Catalogue Note

The tremendous vitality of this carpet’s design is achieved through its highly complex network of swirling vines, which intertwine and overlap each other and flowering or fruit-laden branches. All of these are in planes overlaid by the curling, split and serrated lancet or ‘sickle’-leaves which encircle the horizontal and angled palmettes. Also on the highest plane are the bold palmettes along the central vertical axis and the half-motifs along edges of the field. The two elegant cypress trees, while overlaid by leaves and branches, pierce the pattern vertically. All of these elements are depicted in a rich array of vivid color and executed with a crispness of drawing that demonstrate the superiority of the carpet’s weavers and designers.

While the horizontal palmettes are in symmetrical pairs, the overall pattern is asymmetric with one end of the field having three split medallions and the other end featuring two large half-palmettes and quarter rosette medallions at the corners. It is very likely that this is one half of a design that would have been mirrored, creating a carpet of more typical long and narrow Safavid proportions, see Arthur Upham Pope, A Survey of Persian Art, p. 2385. Pope further proposes that the format of this carpet shows that it was woven for a throne dais or takht and that the throne, and carpet, would have been placed against a wall at one end such it would appear that the Shah were sitting in the middle of a great carpet, Pope, ibid. This proposed function for the carpet stuck over the years, and in the 1976 exhibition Carpets of Central Persia, this carpet was labeled “The Corcoran Throne Rug,” see May H. Beattie, Carpets of Central Persia, Sheffield, 1976, pl. 6, cat. no. 15. Beattie also notes how the carpet can be viewed from either end, as the vines and leaves are directed “alternately medially and laterally,” although she prefers viewing with the cypress trees upright rather than “balancing on their tips,” and illustrates the carpet with this orientation, see Beattie, ibid, p. 50. Whether or not this carpet was woven for a dais, its scale adds to its dramatic impact as the design elements are barely contained within its boundries.

The sickle-leaf design is the most rare of ‘vase’ technique carpet patterns and of the extant pieces known, the Clark carpet appears to be the only one having a red ground. The sickle-leaf motif itself is undoubtedly a Safavid rendition of the Ottoman saz, or curling, feathered leaf motif, such as those seen on the Cairene carpets in this catalogue, lots 1 and 2. The saz appears around 1550 in an album of design elements that would be appropriate in many media including ceramics, textiles, metalwork, book bindings, and carpets, that was produced by the imperial studio of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, see Michael Franses, "The Influences of Safavid Persian Art Upon An Ancient Tribal Culture," in Heinrich Kirchheim, et al., Orient Stars, Stuttgart and London, 1993, p.108. Curling, serrated lancet or sickle leaves became a popular motif in carpets, appearing not only in Safavid and Ottoman court carpets but also in works from the Caucasus, (see C. G. Ellis, Early Caucasian Rugs, Washington, D.C., 1975, pl. 22, the Caucasian 'vase' carpet from the collection of Harold Keshishian), and Mughal India, see Dimand and Mailey, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973, pp. 148-9, fig. 129, cat. no. 55. Not only found in Safavid 'vase'-technique weaving, the curling leaf also appears in carpets from other Persian workshops such as those attributed to Isphahan, with one example being lot 19 in this catalogue, the Lafões carpet.

Most closely related to the Clark carpet design-wise is the sickle-leaf 'vase'-technique carpet in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, see Richard Ettinghausen, Persian Art: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 1985, pl. 30. The Gulbenkian carpet shares a similar design scheme although on a deep blue ground and the design is mirrored from the central horizontal axis such that its dimensions are those more typical for Safavid weavings, more than twice as long as it is wide. The Clark and Gulbenkian carpets also share a similar narrow border with simple band guard stripes. These narrow borders have led some to speculate that they are the inner guard borders to a wide major border that would more comfortably complement the large design elements of the field, see Steven Cohen, “Safavid and Mughal Carpets in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon,” Hali, issue 114, p. 85.

Yet, a narrow border is a feature of so many ‘vase’ technique carpets that Spuhler stated, “The borders of all Vase carpets are exceptionally narrow, and, as in this fragment, they often lack guard stripes,” when writing about the Sarre fragment in Berlin, see Friedrich Spuhler, Oriental Carpets in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin, Berlin, 1987, pl. 86, p. 227. Other related ‘vase-technique carpets with narrow borders include the Béhague ‘vase’ carpet, see Christie’s London, 15 April 2010, lot 100 and Pope, op.cit., pl. 1232; the Wagner Garden carpet in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, see Beattie, op.cit., pl. I; and sickle-leaf design ‘vase’ carpet fragments in the Textile Museum, see Charles Grant Ellis, “Kirman’s Heritage in Washington, Vase Rugs in the Textile Museum,” Textile Museum Journal, vol. II, no. 3, December 1968, figs. 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10a, 16.

The border design of palmettes, rosettes and scrolling, flowering vines on the present carpet is most similar to that on the ‘vase’-technique carpet with fragments in the Textile Museum, Berlin and Cairo, see respectively Ellis, ibid, fig. 1 and Spuhler, op.cit., pl. 86, and Gaston Wiet, Exposition d’Art Persan, Cairo, 1935. While the basic elements of this border pattern are found in many ‘vase’ carpets including fragments in the Textile Museum, Ellis, op.cit, figs. 3, 4, 58, 10a, the motifs are usually more stylized and regular, as most distinctly seen on the Béhague carpet. Ellis sees these changes as an evolution over time and one aspect in setting a chronology of ‘vase’ carpets with the earliest examples being the Berlin, Textile Museum and Cairo carpet and the Clark carpet offered here, see Ellis, ibid., p. 19.

In comparing the Clark carpet with the other sickle-leaf design ‘vase’ technique carpets there are differences in the designs that suggest a rough chronology. The Gulbenkian carpet features a layer of red vines that are thicker than the underlying floral vinery, while the branches and vines on the Clark carpet are all quite fine. On the Clark carpet the sickle-leaves are also more attenuated than the robust, highly serrated foliage on the Gulbenkian carpet. Sickle leaves on the Jekyll carpet fragments appear to have characteristics similar to both carpets with some leaves being elongated like the Clark and others being more thick and feathered as in the Gulbenkian carpet, see Kirchheim, op.cit., pl. 72, pp. 138-9 and Roland Gilles, et al, Tapis present de l’Orient a l’Occident, Paris, 1989, pp. 148-9. In the Béhague carpet and the sickle-leaf carpet once with Miss E. T. Brown, see Pope, op.cit., pl. 1236, the leaves have become more uniform in their drawing and placement across the field, suggesting that these are the latest pieces in the chronology. Ellis, op.cit., p. 19 believes the Clark carpet to be the oldest of the sickle-leaf 'vase'- technique group, dating it to the late 16th century. Scholars since have come to consider the Gulbenkian as the earliest with the Clark and Jekyll examples following closely thereafter in the early 17th century, see Dimand and Mailey, op.cit., p. 77 and Beattie, op.cit. p. 50.

All of the sickle leaves in these carpets are internally decorated with a variety of flowering vines and in many cases they are split in two colors along the vein of the leaf. In the Clark carpet the sickle leaves are split, with a smaller leaf of a different color sprouting from the long leaf and curling in the opposite direction. The Brown and Gulbenkian carpet have some of these extra leaves, however not to the extent of the Clark carpet. Other distinctive features of the Clark carpet are the pair of cypress trees and the pair of shield-like light blue palmettes at right angles to the trees, the fan-like blossoms at the base of the trees and the pair of coiled, stylized blue and white cloudbands which also demark a slight shift in the design to the central vertical axis of the carpet. These bold, rotund cloudbands are found in other ‘vase’-technique carpets, for examples the Sarre/Berlin fragment and two fragments in the Musée des Tissus, Lyon, see Roland Gilles, et al., Le Ciel dans un Tapis, Paris, 2004, pls. 50 and 51, pp. 184-187.

The pair of tall, elegant cypress trees in the Clark carpet are more uncommon on sickle design ‘vase’ technique carpets, appearing on two fragments from the same carpet now split between The Burrell collection, Glasgow Art Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, see Beattie, op.cit., nos. 18 and 19, pp. 52-53. Similar pairs of cypress trees appear in other important Safavid carpets such as the Schwarzenberg ‘Paradise Park’ carpet, now in the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar as well as the 'Coronation' carpet, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, see respectively Michael Franses, “Persian Classical Carpets,” Hali, no. 155, p. 10 and Linda Kamaroff, "The Coronation Carpet," Hali, no. 162, fig. 2, p. 47. Cypress trees have long been revered by the Persians. They are indigenous to the area and have longevity, leading to them becoming a symbol of immortality, and to their choice as a symbol for the Zoroastrian god Mithra, see Susan Day, “The Tree of Life: A Universal Symbol,” Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies VI, Milan, 1999, p. 11.

Trees have been used by man as symbols of life, paradise and the cosmic universe from earliest times to the present, see Day, ibid, pp. 1-13. Since Cyrus the Great built the large garden he called his ‘Paradise Park’ around 540 B.C., Persian artists and authors have been depicting and writing about gardens as a paradise ever since, see Franses, op.cit., p. 7. A favored composition for carpets therefore became the paradise garden with its depiction taking various forms from the ‘Paradise Park’ carpets, to the bird’s eye view ‘Garden’ carpets, to the ‘vase’-technique carpets filled with stylized floral motifs and flowering shrubs. The Clark carpet with its abundance of trees and branches issuing ripe fruits and a myriad of flowering blossoms is the essence of a garden paradise.

A distinct characteristic of the ‘vase’ technique group of carpets is their vivid color range and the highly sophisticated juxtaposition of these colors. In the earliest ‘vase’ carpets, including the Clark carpet, the design is also resplendent in its variety of floral elements and in their differing sizes. Here, the dynamic combination of design and color keep the eye moving over the surface of the carpet . The Clark sickle-leaf carpet also engages our imagination and we are invited into a world of great splendor and abundance by a tour de force of Safavid weaving.

Please note that a license may be required to export textiles, rugs and carpets of Iranian origin from the United States. Clients should enquire with the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) regarding export requirements. Please check with the Carpet department if you are uncertain as to whether a lot is subject to this restriction or if you need assistance.