- 9

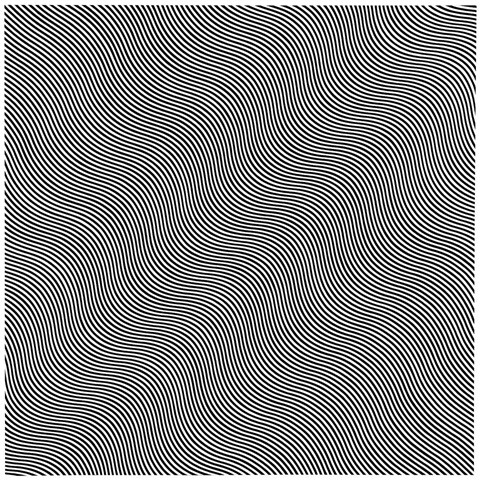

Bridget Riley

Description

- Bridget Riley

- Untitled (Diagonal Curve)

- signed and dated 66 on the side edge; signed and dated 1966 on the reverse

- emulsion on board

- 129.4 by 129.4cm.

- 51 by 51in.

Provenance

Richard Feigen Gallery, New York

Collection Dr Theodore N. Zekman, Chicago

Graham Leader, London

Acquired directly from the above by the family of the present owner in 1974

Exhibited

Catalogue Note

With its highly poised, pulsating composition, Untitled (Diagonal Curve) is the quintessential manifestation of Bridget Riley’s iconic Op Art. Occupying pivotal territory in the evolution of her oeuvre, the present work sees the apotheosis of her search for dynamic equilibrium and is unequivocally her most significant black and white work from the 1960s to appear at auction. Painted in 1966, Untitled (Diagonal Curve) marks the culminating stage of her increasingly sophisticated handling of black and white relationships. It was one of the last works she completed before starting to experiment with colour the following year and saw the completion of what was – and arguably still is - her most iconic and visually arresting series. Aside from the present work, Riley made only four other black and white paintings using this hallmark technique of tightly bunched linear curves, and of these, just one remains in private hands. The other works reside in the prestigious collections of the British Council, The Tate Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

At the time of the present work's execution, Riley was buoyed by a surge of creative energy and huge commercial success on both sides of the Atlantic. Her first solo show in America at the Richard Feigen Gallery in New York was a sell-out success long before the gallery opened its doors to the public and her inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark ‘The Responsive Eye’ exhibition the same year, for which her painting Current was used as the cover illustration, positioned her at the head of a prestigious phalanx of influential international artists whose work shocked or disrupted vision through optical devices and perceptual ambiguities. Giving rise to the term ‘Op Art’, the artists included in the exhibition were brought together by their empowerment and dramatisation of static forms in order to stimulate psychological responses.

The hard-edged zig-zag of her earliest black and white compositions like Blaze and Shiver gives way here to the soft reiteration of a contracting and expanding curve. Tapping into the energies inherent in the spatial relations between the narrow lines, the impression of pulsation reaches a startling and unprecedented intensity, bombarding the beholder with pure energy. Employing the static, balanced square format – Riley’s preferred support up until 1967 – she harnesses the power of simple, geometric forms to create an instant sensation of flux and movement of dizzying proportion; the accomplished epitome of what Riley dubbed ‘Virtual Movement’. In achieving this fine balance between the graphic firmness of line and the kinetic dynamism of our shifting perceptions, the pictorial order is upset by the diagonal ebb and flow of the heaving, reverberating curvilinear lines. Riley here demonstrates consummate mastery over the techniques employed in her oeuvre to date, bringing the flat picture plane into the third dimension in a surging optical effect which pulls the eye across the picture plane along a definite path. Alternating fast and slow movement, the narrowness and proximity of the lines is honed to an unprecedented degree thus heightening the frequency at which the eye has to register the black and white contrast. At the instances where the lines are most tightly clenched, the picture surface appears to buckle inwards, while the agitation created in the eye’s retina causes this part of the image to vibrate, offering contrasting states of tension and release.

This oscillating visual effect – visceral in the truest sense of the word – is the climax of Riley’s insistent and intelligent interrogation of the phenomenology of perception. Her startling – often blinding – optical effects, criticised by critics of the day as being an aggression on the viewer, wrested the area for dramatic confrontation away from the surface of the canvas to the space between the viewer and the work of art, engaging the viewer in a dialectical exchange. But what fascinated Riley was not the dizzying brilliance of such effects, but rather the psychological realms that these effects unlocked. Through the denial of fixity and loss of focal certainty she sought to open up a new range of experience so that we become open to things that were previously less accessible. Her stated aim does not stop at optical ingenuity but seeks the translation of emotion into pictorial sensation.

Riley’s search for ‘Virtual Movement’ took its impetus from a broad range of art historical precedents, most notably the rhythmic visual language that she found in the work of the Italian Futurists which she experienced at the XXX Venice Biennale in 1960. The Futurists, with their overriding desire to register and render eternal the sensation of speed and its emotional character, sought an active engagement between the work and the viewer, a form of communion that Riley translates in her own inimitable way. Riley studied the pictorial solutions of Giacomo Balla in paintings such as Velocità di Motocicletta, injecting the Italian’s sense of sequence and rhythm and the visual pulse that stretches across the entire canvas into her own work. Concomitantly Riley was fascinated by the work of the Abstract Expressionists and Jackson Pollock in particular, whose work she experienced at Tate’s ‘Modern Art in the United States’ in 1956 and at Pollock’s solo show at the Whitechapel two years later. Riley’s precise, rhythmic visual language is in many ways antithetical to Pollock’s gestural technique, however she nonetheless admired his exploration of the architectonic potential of the picture plane and the stress he laid on the evenness of expressive emphasis that lends the work its plastic coherence. Pollock’s open, multi-focal surface appealed much more to Riley than the focally centred situation of the European tradition.

Riley’s destabilisation of the image can be viewed as one of the most radical departures in the history of post-war British Art. It is a testament to the potency and allure of Riley’s images that they were instantaneously appropriated into the universal sphere of mass culture, and today their potency remains undiminished. Instantly evocative and synonymous with 1960s culture, they continue to influence younger generations of artists and offer an arresting and compulsive visual experience that challenges the very stability of our perceptions.